Over decades of Two-Spirit activism and HIV education, Albert McLeod has made indelible lasting impacts on queer Indigenous communities—and gathered a lot of posters, photographs, Pride T-shirts, conference proceedings and even an autographed book from iconic Two-Spirit writer Tomson Highway along the way.

These papers and objects hold stories and snapshots of Two-Spirit life in North America from the late 1970s to today, and McLeod knew this could be important to other Two-Spirit people and their communities and allies, too.

“Along that journey of the last 40 years, I collected a lot of materials related to Two-Spirit liberation,” McLeod says. “I had kept them for quite a while, and I was curious about where they would end up if I passed away. And I thought they were unique enough that … they should be accessible.”

So in 2011, McLeod took the collection to the University of Winnipeg, to see about building a home for these materials so they could be shared with others now and in the future.

“The archive is for people to know that those people, in that 40 year history, were citizens of Canada,” says McLeod. “Many were First Nations, some were Métis, some were Inuit. They had territorial rights. They had Indigenous rights. It is so they cannot be erased from our history because of homophobia and transphobia. They were equal citizens just like everybody else, and they should be remembered. Many of those people from the early ’80s have since passed away prematurely. There are very few of us left alive to reflect on their journey.”

Today, University of Winnipeg archivist and digital curator Brett Lougheed is responsible for stewarding the Two-Spirit Archives.

Since McLeod’s initial donation, the archives have expanded by leaps and bounds, as more Two-Spirit people have brought even more records, banners, videos and even a full set of ceremonial regalia to be housed at the university. The university believes this is the largest collection of material on Two-Spirit people in Canada—and the work is only getting started.

“We are always looking for more,” says Lougheed. “We value the records of Two-Spirit people here, and we want to provide a safe place for those records.”

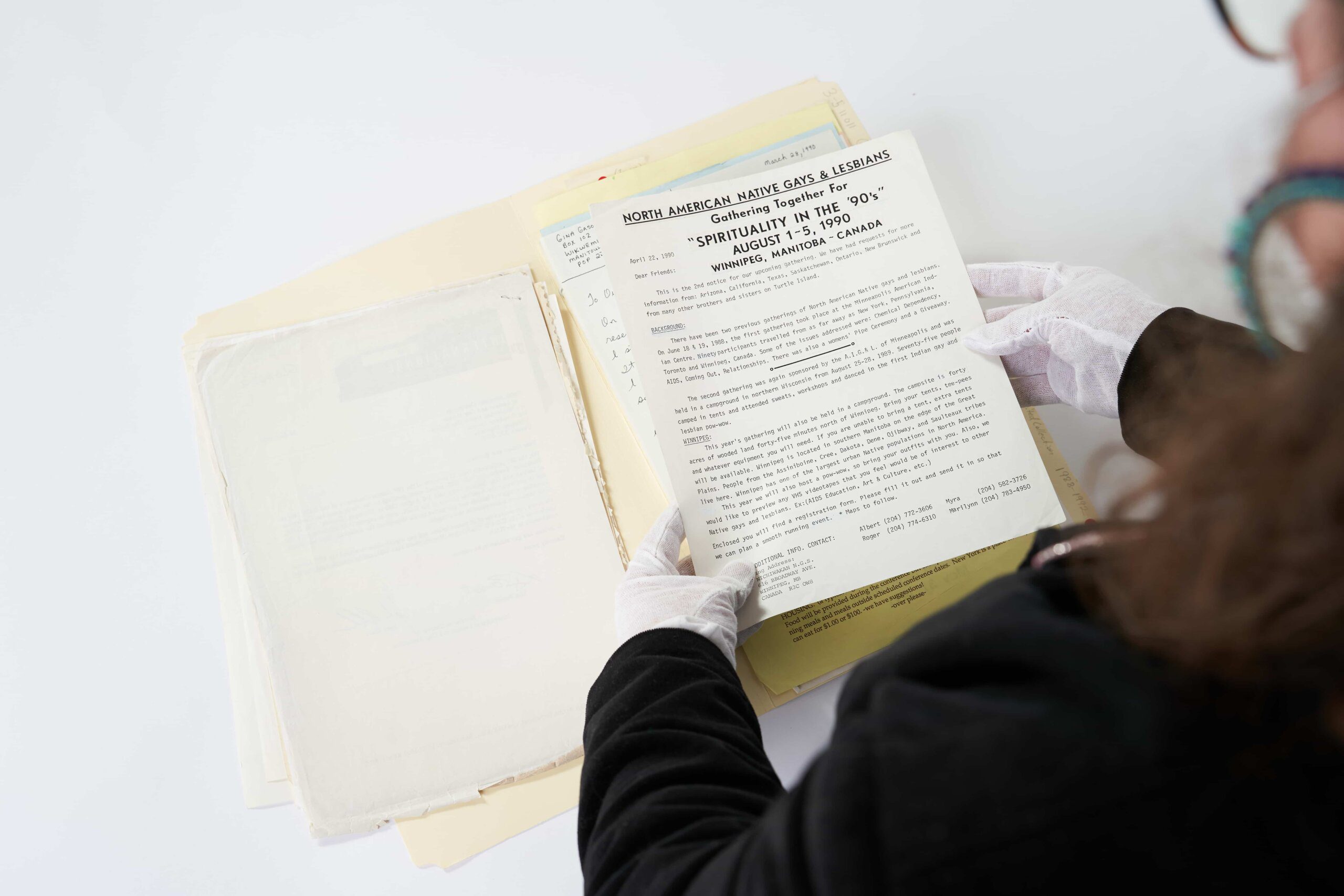

An invitation to the 1990 North American Native Gays & Lesbians Gathering in Winnipeg, Manitoba, is among the items housed in the University of Manitoba’s Two-Spirit Archives. Credit: David Lipnowski/University of Winnipeg.

In the current political climate, where trans, Two-Spirit and gender-nonconforming people across Canada are being targeted by harmful and bigoted legislation, these archives offer an essential tool for people to be able to find their legacies and identities in the historical record.

“One of the challenges that we have to think about is this concern we have with some of the discourses that are going on in Manitoba around ‘parental rights,’ ” says Danielle Marie Bitz, who sits on the Two-Spirit Archives advisory council. “In the context of the discussion going on around us, it becomes more important to keep this archive.

“It becomes more important to have a narrative, and have the material culture that supports that narrative…. In safeguarding these materials, we are preserving a narrative that is being challenged in other spaces right now.”

A thriving, growing Two-Spirit Archive means that queer Indigenous experiences can never be erased from the national narrative, where they have too often been missing, the fabulous animate being (McLeod’s wonderfully apt self-description) says.

“From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself, in the six-volume report, there was only half a page dedicated to Two-Spirit people,” McLeod says. “You can see how white-washing that whole process was, and how it leaned towards heteronormativity and the binary as an ideal for Indigenous people, and how the history and experience of two-spirit people was essentially ignored.

“I think this archive is a good antidote to that white-washing—that erasure—that happened on a massive scale.”

Since the Two-Spirit Archive opened its doors, Lougheed says it has mainly been used by academics—but he hopes, in time, that will change and more people from outside the institution will come and learn and participate in the archive.

When Two-Spirit people donate materials from their own lives, that doesn’t have to mean giving these things up to the university forever; under an Indigenous stewardship agreement, the donors own their records, while the archive takes over stewardship responsibilities like preservation, access and reproductions. If the donor wants their items back, or decides they can be better cared for somewhere else, the university promises to help with that process.

“This is one way in which we are trying to decolonize our practice and make the donation process less frightening and more appealing to folks,” says Lougheed.

McLeod hopes more people—especially older Two-Spirit people—will choose to share their papers, records and objects telling more stories of queer Indigenous life through the archive.

“I want to encourage more people from my generation to donate what they have,” McLeod says. “I understand there is still a lot of fear and concern around being targeted for being out. It’s still very real in Canada.”

“But queer Indigenous people are part of Canadian history, and every person has a right for their story to be told.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra