Content warning: This story mentions residential schools and abuse.

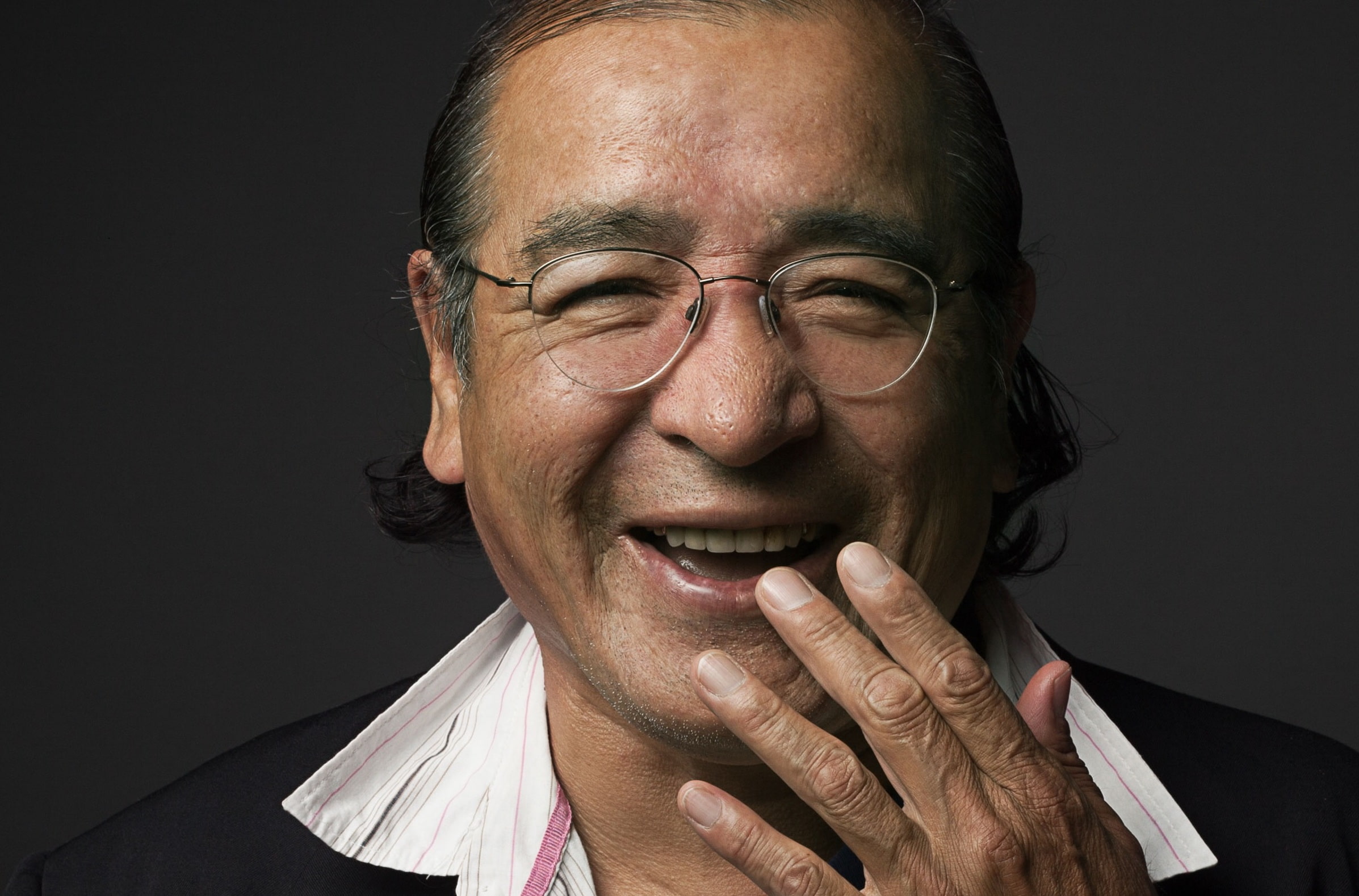

Playwright, author and performer Tomson Highway made a particularly picturesque entry into this world.

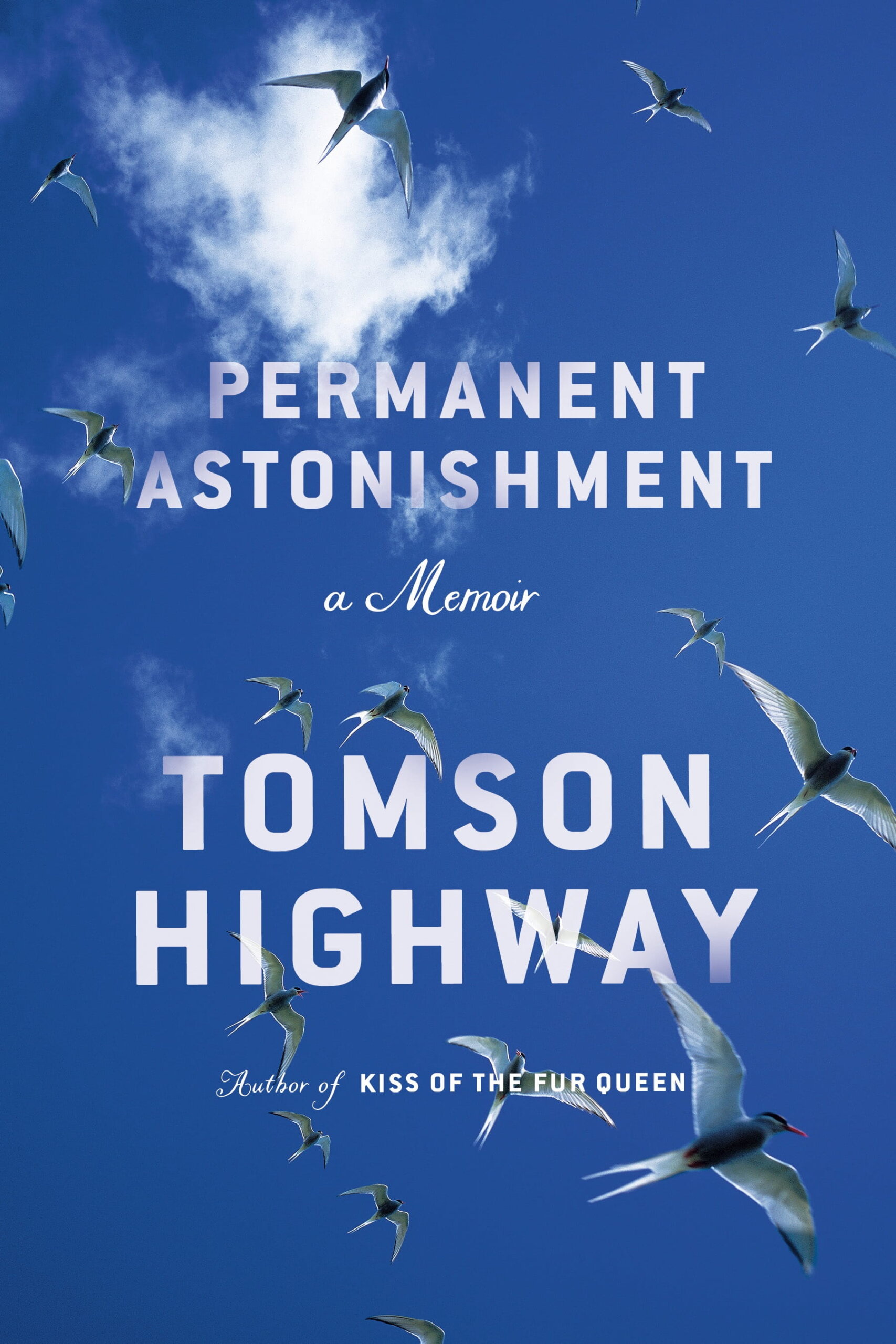

“And there, with nothing separating my mother from that snowbank but a thick wool blanket and a carpet of spruce boughs—with our huskies tied to trees behind our tent, howling with their cousins, the wolves, on the mainland two miles away, a plangent chorus that makes one weep—I was born not male, not female, but both, in the early-morning hours of the sixth of December, 1951, the Feast of St. Nicholas,” he writes in Permanent Astonishment, his first memoir in an illustrious career that has seen him write a bestselling novel (1998’s Kiss of the Fur Queen), hit plays, musicals, essays and children’s books.

The memoir focuses on Highway’s birth and upbringing in the 1950s and ’60s, mostly in the vicinity of Reindeer Lake, a region of Northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan just south of what’s now Nunavut, and almost 1,000 kilometres north of Winnipeg as the crow flies. His nomadic family—Highway was the eleventh of 12 children, though five siblings died in childhood—lived on various islands, using the isolated Indigenous village of Brochet as their base. Though Highway now lives most of the year in Gatineau, Quebec, with his partner of 36 years, and has travelled all over the world, by the end of Permanent Astonishment, he’s only (only!) gone about 430 kilometres south, to attend Guy Hill Indian Residential School on Clearwater Lake, near The Pas in Manitoba. There, he learns English (and some Latin), how to play the piano and that he’s an exceptional student.

“Within three years, the little old nun with the face like a road map will enter my name in the Kiwanis Music Festival which takes place every late February in The Pas and I will beat out all those privileged middle-class white kids in what I learn, only years later, is a racist town, and win a trophy and a scholarship,” Highway writes. “As an adult, I will take those lessons, turn them on their head, and transform them into a million-dollar business.”

Late in the book, Highway briefly recounts an experience of sexual touching by a priest while in the residential school system, which officially operated in Canada from the 1880s to 1996. Over many decades, countless Indigenous people have come forward about their abuse, sexual and otherwise, by this system. But that horrible history is not key to how Highway sees his life story. “And one day, I hope they write about it because I can’t. And to those who can’t, I have tried my best to write this story of survival for you.”

Instead, Permanent Astonishment propels itself wholeheartedly toward joy, whether it’s the joy of the Cree language, the naughty nicknames for friends and rivals, the white-sand beaches of Reindeer Lake, of dances and school sporting events, of escaping harrowing near tragedies, his father’s success as a commercial fisherman and his mother’s lapwachin (a cake-pudding hybrid). Though Highway gives readers few hints of his future life as a world-famous writer and musician, he makes a strong case for how his singular upbringing gave him the tools to succeed.

You write with so much beautiful detail about the world that you were born into. How your family lived, the adventures they had and what the community was like in the 1950s and ’60s. When you sat down to write the book, what was your mission?

My mission was to celebrate my parents. That was the first impulse. I come from one of the most extraordinary marriages on Earth. No exaggeration. One of the best marriages that I know of, anyway. I always say I come from the kind of marriage they can only dream of in Hollywood. You will never be able to make enough money in Hollywood to afford the kind of marriage I come from. There was love and laughter and kindness and wisdom and beauty. They were physically beautiful. My father had a kingly bearing; he was a world championship dogsled racer. I had a spectacular childhood, one of the most spectacular times anybody could possibly have on the face of this Earth. I celebrate that.

Sometimes it seems that you’re almost like a historian or anthropologist documenting things like your mother’s cooking, fishing trips, the Cree language, the landscape, the wildlife—like you’re almost afraid it’ll be lost to history if you don’t get it all down.

You’re right, because that lifestyle has gone. I’m the last of a kind and to preserve it was a secondary purpose for writing the book. The third was to show that, you know, sad things have happened to us, because sad things happen to everyone everywhere, but there’s too much concentration on the negative stuff. So I wanted to write beautiful stuff about our culture that should be celebrated. One aspect of it that people don’t know about is the humour, the humour contained in the Cree language. It’s the funniest and most ridiculous language on Earth. In every second syllable in my language, there’s a kick in the pants. Even the way the syllables move on the tongue makes you laugh. In Cree, when I call people to talk, within the first two syllables, you’re laughing to beat the band and as soon as you switch to English, you stop laughing. It’s interesting. I’m writing a book about the Cree language right now as we speak.

You’re looking back at your childhood over a very long period of time. How did you conjure all those memories and images?

I’ve heard the stories over the years many times from members of my family and friends and relatives. And I have a good memory. But my memory is selective, like everybody else’s. As it says at the front of the book, it exists halfway between dream and reality. I do bend the stories, I do exaggerate, because the Cree storytelling tradition has exaggeration as part of the story, but the basis is pretty accurate.

You mentioned that this book is a celebration of your parents, but you also write very affectionately about your younger brother, René Highway [a renowned ballet dancer who passed away in 1990 at age 35].

It is a celebration of my brother, too. I don’t miss him at all—he’s here in this room with me. I’m not as beautiful as he is by any stretch of the imagination, but I do have his lips. I have his voice. I have his ass. He had a gorgeous ballet dancer’s ass and so do I. I flash it whenever I can.

You write about you both being feminine boys, being picked on, but also being tough and resilient. Was this shared Two-Spiritedness part of what gave you two that special connection?

Absolutely. The older brother who I mention very few times in the book, I leave him out of the picture mostly, out of respect, because he was ashamed of us, he disassociated himself from us and I don’t want to hurt his feelings. But he didn’t take care of us, whereas I took care of my younger brother all the way to the end, and I’m very proud of that.

The book recounts a lot of your experiences attending a residential school near The Pas. I was surprised that only briefly do you zoom out and place your experience in the larger context of the abuses and deaths that have been connected to the residential school system. Can you tell me a little bit about why you handled it that way?

One way of putting it is: One of the greatest privileges of my life is to have been given the opportunity to learn your beautiful language so I can listen respectfully to what you have to say. [Highway speaks a few sentences in Cree, which the interviewer doesn’t understand.] So who’s the privileged one here? The one who speaks one language or the one who speaks six? So I found that aspect of it a very positive experience. I love learning. I’ve learned several European languages, including Latin. The Catholic mass was in Latin until 1962; I was 10 in 1962. Then I remember having to learn those prayers all over again in English, though we didn’t speak it properly at the time. That would give me a challenge, and challenges are the best because once you overcome them, you’ve made yourself stronger. When I was a baby, I was speaking two languages already, Dene and Cree. That’s been a tremendous boost for my writing and my career and my thinking and my life. I thank whoever gave me the opportunity to learn English because I love it, I love speaking it and writing it and making music in it. And I learned how to play piano in a way that no other boy in Canada has ever learned to play.

“I’ve lived out my promise to my fantastic father. My entire life has been about positive energy.”

My father told me, when he put me on that bush plane the first time, “You’re going to go down there and you’re going to be amazing.” He deeply regretted never having gone to school himself and he wanted me to have educational opportunities that had never come before. My thinking was, “Dad, if you weren’t able to go to school, because there weren’t schools up there back in the day, then I would do it for you, I would go to school for you and I would do amazing things with my education.” That’s exactly what I’ve done. I’ve lived out my promise to my fantastic father. My entire life has been about positive energy, I’ve had not a drop inside me of negativity. You cannot make me not have a good time. It’s impossible.

That’s a wonderful skill to have.

My father was the most positive man on Earth. The best lesson he gave to us: When you make a disaster, you turn it around and make it into something absolutely spectacular. That’s what mistakes are for, so you can teach yourself to not make that same mistake again.

When was the last time you were back in Brochet?

I go twice a year. I’ll go once in December, once in August. I’ll spend two months at a time up there but, of course, these last two years have been different. I love December, there’s nothing like the freshness of the snow up there in wintertime. And for some reason the first three weeks of August have no wind, so the lake is super calm, like glass. So I like island-hopping, we’ll camp out on the islands all the time.

How has Brochet changed, or not changed, since the ’50s and ’60s that you’re writing about?

It’s changed radically. Around 1973, electricity arrived in Brochet. Everything changed overnight. Television came in, the telephone came in, the electric stove came, so the woodstove went out the window. The airport was built, so planes no longer came into the village. The romance is gone, and the housing development has destroyed the natural landscape. It used to be back in those days, there was a field of grass with raspberry bushes every step of the way. Our house was about 200 yards from the one store in town, which normally would take about 10 minutes to walk to, whereas in raspberry season time, it took two hours because we were so busy bending down, squatting on the ground and picking raspberries every step of the way. All that grass and the raspberry bushes are gone. It’s all gravel. The all-important method of travelling from point A to point B now is by truck and car and Ski-Doo. It’s all so mechanized. Of course, out of the village, the landscape is still as stunning today as when I was a child.

Permanent Astonishment only covers your life up to the age of 15. Do you have plans for more memoirs?

I intend to write five volumes. The next one will take me from age 15 to 30, so high school in Winnipeg, then at the University of Manitoba and later Western University, then I was a social worker for seven years. The third book will chronicle the next 15 years, which is when my theatre career exploded. Then the next book is from age 45 to 60 when I became a novelist and started a revolution, in the sense that we invented an industry from scratch, which is the Native literature industry, where we’ve developed a voice that has become known worldwide. I’ll be 70 in December and if I’m lucky enough to live to be 75, that next 15 years is the fifth volume, and that’ll be about the aging process. It’s a beautiful, beautiful transition to be approaching the end of your life. In English, death is a negative. In Native cosmology, death is a positive; it’s not an ending, it’s a beautiful passage to another state of being.

If you’ll allow me to ask about what you’re probably saving for a future volume of your memoirs, I’d like to know more about your relationship and the secret to your lasting so long as a couple.

We love each other deeply. He’s 72, I’ll be 70. He is the kindest man alive, he’s the best caregiver in the world. We make a great team. For me, one explanation of love is to come home and just find all your clothes washed and folded and put away. We’re compatible on the intellectual, emotional and spiritual level. It’s just the physical part of it that’s tricky. You can only have sex with somebody for so long, you get tired, including in the heterosexual community. Let’s put it this way: We let ourselves out on a very long leash and we have very open minds about that.

On your book jacket it says you live part of the year in Naples, Italy. I’m envious. How did you manage that?

Oh, we’ve travelled the world. I’ve been to 62 countries. Some people will travel for two weeks and come home to Canada. Whereas our style of travelling, we go somewhere and we stay for 14 years. We lived in France for 14 years, six months a year, so my French became perfect during that time and then we decided that since French was under my belt, I wanted to try Italian. I also spend a lot of time in Brazil. I live one month every year in Rio de Janeiro. I’ve been there 15 times.

When you were a child in northern Canada, could you have imagined this life you have for yourself?

Well, I had prepared for it. The groundwork had been done. The foundation was laid. And when you have a foundation like that, it’s hard to fail. You put yourself there. To me, happiness is an act of personal will. It’s a personal decision. You decide to be happy or you decide to be unhappy. Talking about the negativity of descriptions of the residential school experience that’s out there in droves, my final response to that is: Living in the past is a surefire recipe for failure and misery. Contrariwise, living in the present and the future is a surefire recipe for happiness and success. And that’s all there is to it. I have a successful life because I willed it to be.

I saw your play, The Rez Sisters, in 1988 and it was such a landmark play. Few people were telling stories like it on such a big platform. [Set on a fictional Ontario reserve, it centred the lives of seven Indigenous women, one of whom had a female lover.] In recent years, there’s been such a growth in Indigenous activism [like Idle No More and the land back movement], and a flourishing of Indigenous art and artists. Do you feel optimistic about what you’re witnessing?

Yes, definitely. That’s why I do what I do. My work as an artist is only secondary. My real work is that I’m still a social worker. I’m here to work with the spirit of the community. The third gender, their responsibility became the emotional and spiritual life of the community, which is where the shamans and the visionaries and the artists are. That’s who we are. We are here to take care of the emotional and spiritual life of our community. And because the artistic production has grown so, so much in the past 40 years, that’s what’s happening. We’re healing the spirit of the community. That’s our job. And that’s my real job.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It was conducted prior to the Nov. 3 announcement that Tomson Highway won the Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction for Permanent Astonishment.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra