At a funeral following the tragic death of a young man to a firearm accident, a small party gathers under a cramped gazebo. Some are openly crying, others fidgeting in stress, their grief palpable. The mood is sombre until Joe Exotic takes the stage, his frizzy bleached mullet stuffed under a black cowboy hat. Standing directly in front of the boy’s mourning mother, he starts a monologue about how much his late husband liked to rub his genitals in Exotic’s face: “They were like golden nuggets.” The boy’s family members avert their eyes.

Such a scene is not out of place in Tiger King, the show that the internet claims is better than any other to watch during quarantine. As collective anxieties rise, it seems everyone is scrambling to latch onto any piece of media that promises distraction from apocalyptic thoughts and sequential panic attacks. And distracting Tiger King certainly is: The Netflix original is a barrage of ever-increasing absurdity, packed to bursting with big cats, allegations of brutal mariticide and polygamous cults. The internet is eating it whole without pausing to chew.

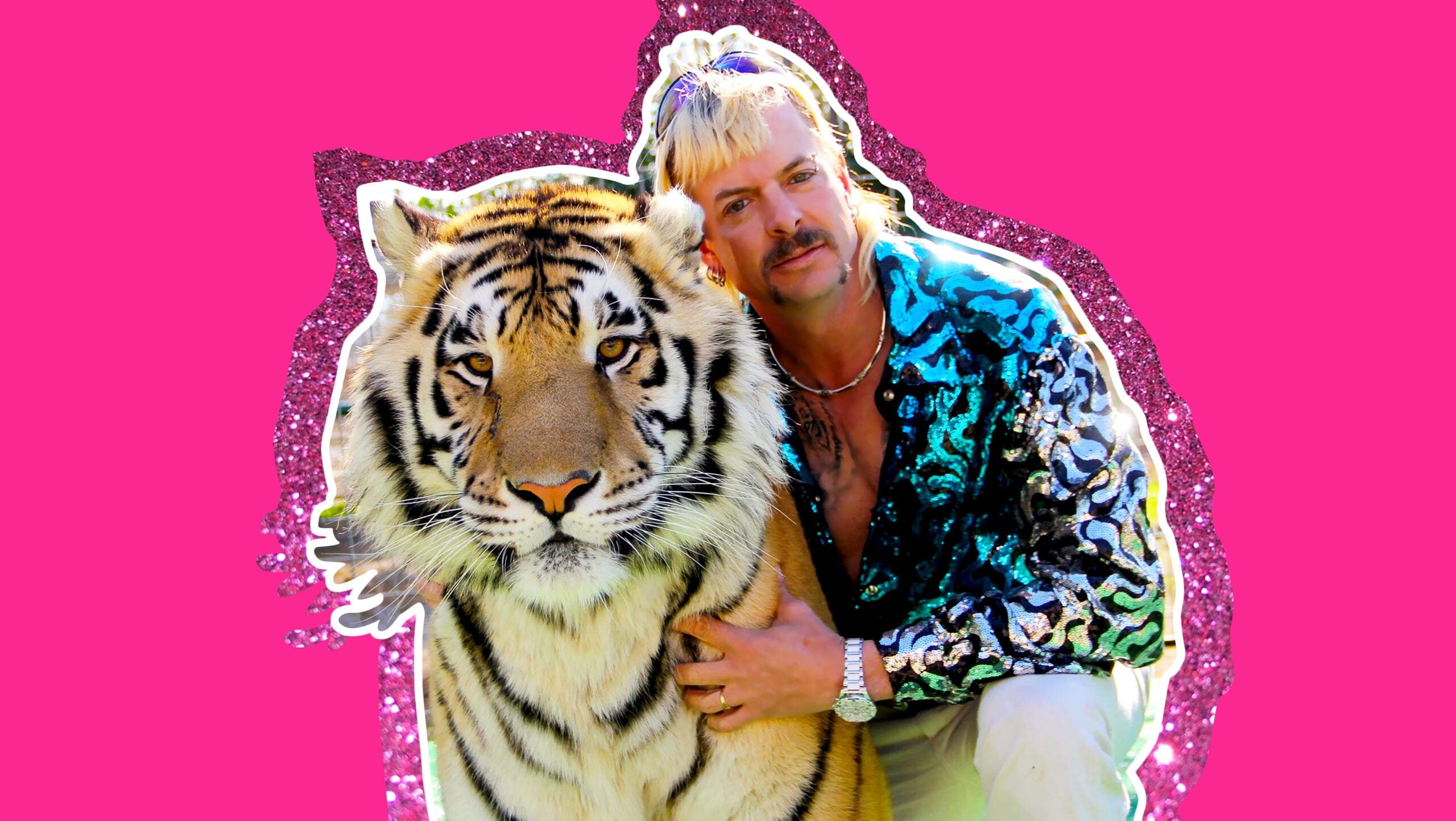

Online queer communities have especially been awash with discussion of Joe Exotic—the mullet-sporting, gun-toting, gay zookeeper vlogger around whom the series centres. Curiously, much of his representation on the gay internet isn’t focused on his idiosyncrasy but on his relatability. Timelines are flooded with tweets heralding Exotic as a “gay icon.” Scrolling through social media, it’s not uncommon to encounter a picture of Exotic, shirtless in a leopard-print jacket or in some equally flashy getup, with captions such as “literally me,” “style goals” or “he looks like every lesbian and I’m here for it.” Queers, in a way that may or may not be ironic or post-ironic, boast giddy identification with a man who built his pre-incarceration life around manipulating teenage boys, abusing tigers and advocating violence against those who disagree with his abuse of tigers.

It’s concerning to see our community members call an exploitative, manipulative man a “gay icon.” But if this doesn’t sit well with you, don’t worry—you’re not standing alone at the edge of a screaming crowd of J.E. stans. Others have been tweeting their discomfort with this wave of idolization. The foundation of their critiques tend to be grounded in bewildered confusion rather than attempts at finding some sort of explanation. It’s tempting to point toward the magnetism of Exotic’s eccentric aesthetic, or how titillating it is to see an unapologetically queer person push his way into spaces dominated by hypermasculine heterosexuals.

But perhaps the flood of community goodwill toward Mr. Exotic has a historical basis—one that’s grounded in the Hollywood archetype of the queer villain.

If we crack apart the glittering facade of one of cinema’s favourite tropes, we might discover that our current fascination with the tiger king isn’t particularly odd or surprising. Millennial queers need only to think back to our childhoods: Our generation grew up with a dearth of queer representation in media, and when we did see ourselves in movies or television, we were primarily reduced to the role of the eccentric and flamboyant villain. To speak of queer representation in the ‘90s is to speak of Jafar, Scar, Ursula, Buffalo Bill and Ray Finkle, the villain in the first Ace Ventura movie (we try not to think about that one).

“With queerness cinematically associated with deviation itself, the queer-as-villain trope came into itself in full force. This is the legacy that Joe Exotic fits into”

Before that, the history of LGBTQ representation in Western media is convoluted and depressing. Before the 1930s, it was relatively common for queers to be explicitly portrayed in films. This representation can even be traced back to the birth of the motion picture: William Dickson’s Dancing Men in the Black Maria (referred to by some as The Gay Brothers) from 1895 depicts two men engaged in an intimate dance together, and is one of the earliest surviving films of its kind available to us. In Charlie Chaplin’s 1916 film Behind the Screen, Chaplin kisses Edna Purviance while she’s dressed as a man, causing a passerby to take them for gay lovers and harass them. During the 1920s obsession with Westerns, the figure of the “sissy cowboy” takes the stage—including an early Laurel and Hardy film, With Love and Hisses.

It isn’t as though this was a period resplendent with multi-dimensional, respectful portrayals of LGBTQ people. In nearly all of these films, the LGBTQ (or “sissy”) characters were meant to be villains—comic relief used to scandalize the audience. It was rote for the queer to be killed off before the reel stopped spinning; homosexuality was still taboo, and the audience was meant to find the characters repulsive, not to identify with them. But queerness-as-evil had not yet begun to permeate everything in Hollywood—it was still confined to its specific roles of the feminine man, the rugged ugly woman or the transgressive pervert.

Everything changed in the spring of 1930, with the introduction of The Motion Picture Production Code. Informally known as the Hays Code, it mandated films to adhere to strict moral guidelines: Anything that could be conceived as “lowering the moral standards of the audience” was banned. The code contains an entire section on depictions of sexuality, with any sort of “sexual perversion” outright banned. Representations of queerness went underground—portrayals of queerness were now insinuated rather than explicit. The effects of this shift are long-reaching and insidious, even though the code was revoked in 1968. To this day, it is more common to see a queer-coded character than one who is named as such.

“When we look at Joe Exotic in all his flashiness, we see in him the queer villains of our childhood. And out of habit or rebellion, we claim him as our own”

Queerness had always been understood as that which is “other”—the perverted, strange underside of respectable heteronormative society. But that was further intensified by the unmooring of queerness from actual LGBTQ characters, when queerness became some incorporeal, intangible chimeric energy. With queerness cinematically associated with deviation itself, the queer-as-villain trope came into itself in full force. This is the legacy that Joe Exotic fits into: He nearly perfectly embodies the excessive, flashy, flamboyant, amoral narcissist that has become a villain archetype.

In what was otherwise a desert in terms of media representation, the queer-as-villain trope has given us a lot to work with. It’s true that these characters are vicious, proudful and manipulative. But they are also quite fabulous. We lauded The Little Mermaid’s Ursula for her magnificent mile-high eyelashes, giggled gleefully at Hades’ antics in Hercules, revelled in the fabulousness of The Powerpuff Girls’ Him. “If society sees us as these villains, so be it,” we sneer. “They look gorgeous anyway.” There’s nothing wrong in such a reclamation—after all, these are just fictional characters who exist only in the realm of the imagination.

A problem arises when such a relationship to queer villainy is extrapolated to real-life situations. When we look at Joe Exotic in all his flashiness, we see in him the queer villains of our childhood. And out of habit or rebellion, we claim him as our own.

His scrappy, delinquent nature, relative powerlessness and the eagerness of those around him to frame him as a menace all harken back to the tropes we’re accustomed to. It’s so tempting to conceive of him as the queer underdog who was given the role of villain not because he deserves it, but because the stage was set by the heterosexual society that always puts us in such a position.

The problem is that, unlike other queer-coded villains, he is a real-life person who has caused real-life harm to others. He’s so cartoonish in his diligence to be as excessive and styled as possible that it can at times be difficult to remember this. But he’s a man that takes advantage of vulnerable teenage boys and grooms them into who he wants them to be. He’s a violent, desperate and narcissistic man who would kill those that stand in the way of what he wants, who is unable to admit wrongdoing or be accountable for his choices.

That we reflexively identify with such a man shows the time has come to be more critical of these reclamations. Queer representation in media today still has a long way to come (I’m looking at you, Scarlett Johansson). But there are people on the big screen we can see ourselves in that don’t resemble comic book supervillains—characters that are multi-dimensional and complicated. We can have characters who cause hurt and are crude and messy but who are trying in their own way to do good for themselves and others (think: The L Word’s Finley, The Favourite’s Sarah, or Marianne in Portrait of a Lady on Fire); we don’t need to remain attached by spite to queer villains. The time has come to break our bond with the Joe Exotics of the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra