Of the many alt-girl relics of my ’90s adolescence, there is one film that still feels extra charged with a queer supernatural frequency.

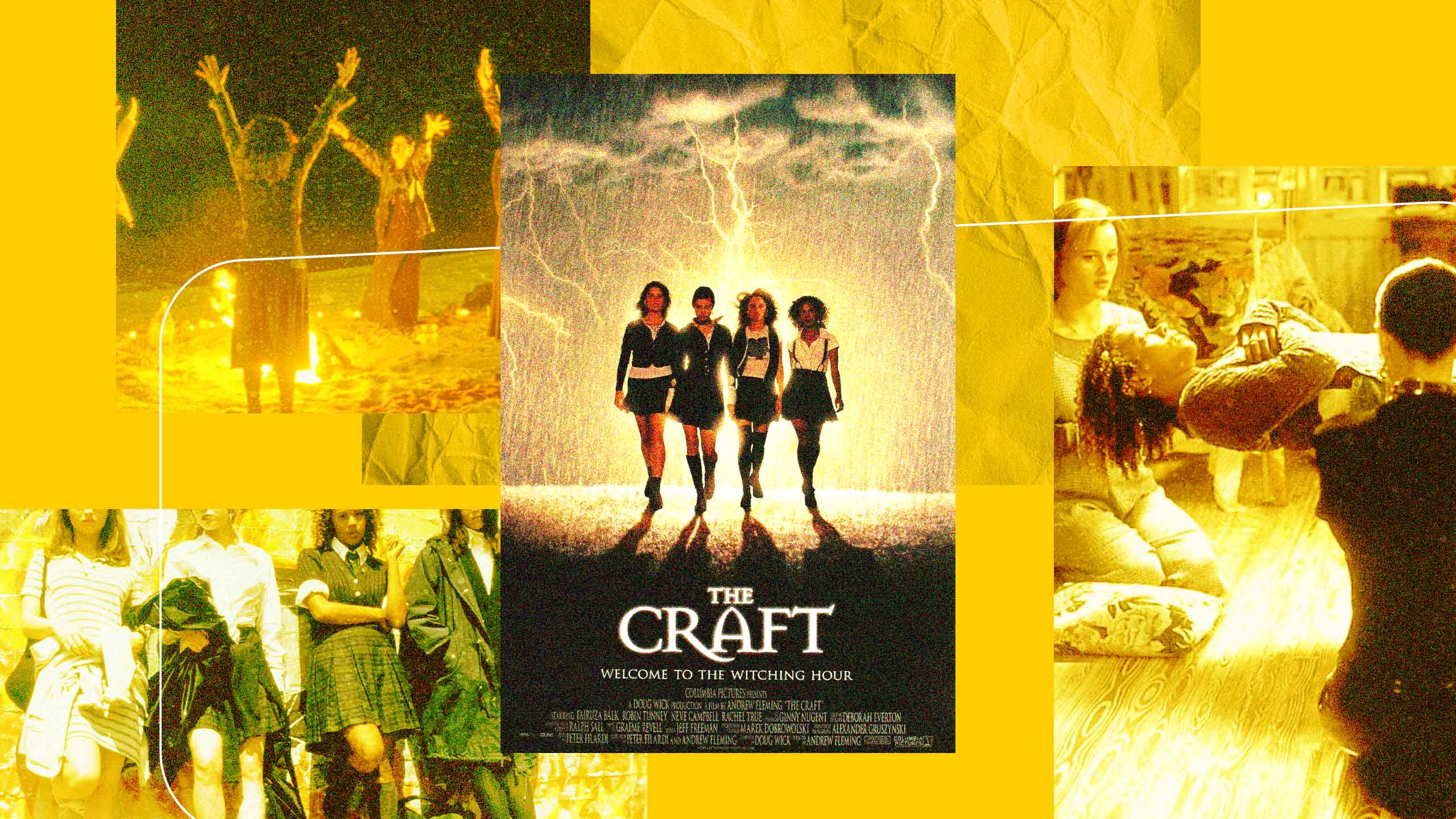

Andrew Fleming’s 1996 cult film The Craft cast the kind of spell that tweenster me didn’t know she needed in the dark, sticky cinema at Toronto’s Eaton Centre, squished between three other giddy girls from my junior high.

In hindsight, I was more than ready for levitating girls; bad girls with vulgar mouths nicknamed “the bitches of Eastwick”; psychic girls with scars, Sassy magazine subscriptions and terrifying rage. Watching trickster goths in spiked collars and desecrated rosaries turn a candlelit slumber party into witchcraft, a queer horror rite of passage had been ignited. Most importantly, I was thrilled to learn that if girls chant incantations against terrible boys in a golden meadow, they must initiate the spell with blood rituals and gay kissing. It’s for these reasons that I owe so much of my lesbian coming out story to The Craft’s girl gang of teen misfits invoking spirits, Sapphism and snark.

When I eventually learned that Fleming was also queer, I thought, “Of course.” Such a tale of traumatized teen loners can’t help but brim with real-life queer angst. In comparison to other mainstream witch films and TV series at the time—think Hocus Pocus (1993), Practical Magic (1998) and Sabrina the Teenage Witch (1996–2003)—Fleming’s film has come to represent a darker and dykier interpretation of the era’s glossy, grrrl-powered witchcraft. And while not as explicitly homocore as the films of the New Queer Cinema, The Craft has since accumulated endless readings and fixations that position it within a queer girl canon of ’90s popular culture.

Set in a quaint suburb of L.A., The Craft follows the occult misadventures of four teen outcasts—Nancy (Fairuza Balk), Sarah (Robin Tunney), Rochelle (Rachel True) and Bonnie (Neve Campbell). While tame in comparison to today’s expressions of teen queerness, the film offered a bold and defiant look at female sexuality and rebellion for the angsty mid-’90s generation coming of age. Despite the MPAA enforcing an R rating due to the girls’ experimentation with “black magic,” the supernatural horror film was a surprise commercial success, earning $6.7 million on opening weekend. Critically, the film seemed to resonate with teen audiences, winning Tunney and Balk an MTV Movie Award in 1997 for best fight scene while American film critic Roger Ebert panned the film in an early review, calling the plot “below our interest” before going on to declare the “movie’s failure” to be “one of imagination.”

I came out the same year as The Craft was released. I was on the cusp of my last month of Grade 7, after having spent a full year at a new school. At that age, any change that disrupts a kid’s routine has the potential to turn daily, mundane activities into an endless, tumultuous free fall; an act of flying.

“We recognized something queer about the film’s brand of teen girl defiance and anger”

The Craft became a foundational film for me and my friends, signifying a form of teenage rebellion we had never seen before. At an age that finally allowed for more independence, seeing such a queerly coded film in the cinema was also a newfound opportunity to continue building horror film rituals in dark theatres, without parents, turning candy consumption and communal viewing into a sacred practice of feral autonomy.

More than that, though, we recognized something queer about the film’s brand of teen girl defiance and anger. Watching girls cast curses as a means to fuck up and resist white heteronormie power dynamics made just being in that sketchy theatre feel like an act of rebellion for us. In particular, Nancy’s volatile sexuality made me squirm.

By the time The Craft was released, the formation of my tight-knit childhood friend group had vastly shifted. Nine months spent at a new school with a horde of unfamiliar kids meant an inevitable splintering off as I explored other connections. My social life was experiencing a fracture from its previous safe familiarity—and I saw that fracturing mirrored in the film’s depiction of the fraught friendship dynamics and the turbulent transitions of adolescence.

I soon began to waste school hours marvelling at what I thought of as the alien-girl invasion, a grungier new cohort of girls with multicoloured-hair, cropped Tank Girl T-shirts and torn, thrifted Levi’s and purple-and-green fingernails clasping cracked cases of Hole’s Live Through This and Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill albums. I wasn’t entirely sure how to navigate this new teen terrain—maybe the power that came from (poorly) practising Wicca would help me survive the crushes I was having on girls, and Grade 7.

Occasionally, I would spot a flash of my first crush’s Manic Panic hair across the rows of the new public library that opened a block from our school. It was the same library where, that winter, friends dared me to sign out books from the Health & Sexuality section, clinical texts on coming out and homosexuality. Instead of educational aids, they felt like cursed modern-day spell books foretelling depressed grrrl premonitions.

The snarled and sparkle-goth culture I saw projected onscreen in 1996 was a livewire connecting me to the disruptive hellions and bad girls wandering the hallways of my new school. I longed to cast spells with them and for them.

When I say that I came into my queerness through the slumber-party-slasher-movie-séance pipeline, I mean that the strange powers that a bunch of excitable girls ignite when they’re left to their own volition are irreparable and disarming. Through Magic 8 Balls, séances, Ouija boards and DIY games like “Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board,” my friends and I tried, desperately, to gain agency and control over our lives. We looked to the occult to help us predict our futures, or at the very least help us decide on what pizza toppings to get, who to prank call next and who would get their period first (spoiler alert: it was me).

Slumber parties felt dangerous and comforting all at once. They were rites of passage that fuelled gossip, mischief and, for me, aided in my queer awakening. This homosocial realm offered freedom away from boys, teachers and parents. Instead, we nurtured these spaces of girl chaos directed toward the deviant, unfamiliar spirit worlds that felt as marginal as I did as a closeted teen.

What resonates with me still is The Craft’s depiction of how the occult can function as a source of queer and feminist curiosity amongst teen girls. The film’s slumber party séance is a crucial moment of rebellion for the angsty witches keen on revolting against the restraints of Catholic girlhood. When the coven’s only Black girl, Rochelle Zimmerman levitates during a game of Light as a Feather, the whole coven is responsible for this otherworldly feat. And when Nancy compares the game’s premise to fingerbanging, a match has been struck for me.

I didn’t have the language for it then, but I knew there was a particular potency to seeing my desires reflected onscreen for the first time. Back in the dark cinema, watching girls behaving badly, my friends and I delighted in the shared experience of these risqué scenes. We watched as the girls shoplifted, discussed the painful mess of being on “the rag,” skipped school to sip each other’s blood and felt slightly corrupted by the tasty taboo of it all. As an adult, I realize now the girls’ blood ritual in the meadow was Fleming’s subtle acknowledgement of the era’s spectre of AIDS. As one of the film’s more explicitly queer instances, the scene boldly defied the unspoken stigma that permeated pop culture at the time.

For me, so much of The Craft was an act of recognition. In a scene early into the film, Sarah Bailey sits in her new French class. She twirls her pencil into a telekinetic torpedo on top of her desk. Bonnie is the only classmate to acknowledge her remarkable magical abilities. To everyone else, Sarah’s merely a nuisance, an obnoxious “snail trail.” This witch-grrrl meet-cute allows Sarah and Bonnie to create an intimate signal of kinship. The shared recognition also happened to heighten the growing necessity I felt for interpreting acts of queerness around me, a telepathic sense in its own right, I’d later realize.

The powerful collectivity of the coven’s alienation was initially shown as an asset. At first, the witches form intimate bonds as a result of their individual traumas and alienation. For the mid-’90s, the power born through this type of connection became an alt-expression of friendship and feminist community I hadn’t really seen onscreen until then. It was a sometimes complicated interpretation of independence that I saw reflected within my own friend group at the time. Flemming found a generative way to discuss toxic intimacy, infighting and the turn to more sinister sisterhoods.

Twenty-seven years later, I realize now that the film quite accurately, and inadvertently, invokes (and then destroys) the Queer Nation emblem that “an army of lovers cannot lose.”

Sequestering themselves from parental supervision allows the witches to tap into the peculiarities of their queer, weirdo powers. In the scene following the slumber party séance, the girls stride through the school with Letters to Cleo’s angry grrrl ballad “Dangerous Type” summoning them straight toward us, and to hell.

What struck me most was that, despite making a display of themselves, no one around them seems to really notice. Instead, the spectacle of high femme bravado is reserved as a secret shared with just the audience.

At the time of its release, Nancy Downs epitomized for me the paradoxical queer dilemma of “Do I want to be her or do I want to be with her?” Every time Nancy made an explicitly lesbian remark (see: “I love a woman in uniform”), my skin prickled. A queer villain, a working-class witch and a sexual assault survivor, Nancy manifested her power and resistance by hungering and devouring the scent of girls, then viciously murdering predatory high school boys. Rarely was teen girl pleasure represented as anything but monstrous in the media I consumed at the time. For Nancy, though, there was delight in the politics of female monstrosity, in the way it enables the destruction of norms. Her rage and sexuality helped to queer the ’90s bad girl trope in an iconic way, creating new visual keepsakes for liberating the hysterical witch from her trauma and watching her fly.

Still, no one talked about why a girl, disfigured and restrained to a sanatorium bed, was a terrifying image to witness for girls coming of age. I know that it resonated with me in a way that felt defiant and exhilarating. The film’s treatment of Nancy still complicates the way I identify with girls acting dangerously onscreen. Often, queerness feels like a strange power. Sadly, identifying as a dyke still requires occasional shapeshifting to conform as a means of self-preservation. The Craft bookends its opening and closing credits with dreamy, soft clouds; a haunting variation of the witch on her broom. With girls drifting in and out of celestial voids, the film balances its liberation with the catastrophic.

In refusing to sanitize its dykiest witch, the hard-candy shimmer of The Craft remains a dangerous omen preserved for young queer misfits to come. This is what happens when the brutality of queer adolescence can’t be restrained or saved by the spell.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra