Distraught from the AIDS epidemic and furious over the administration of Ronald Reagan’s neglect and stigmatization of the ill, queer filmmakers in the U.S. used newly available commercial camcorders to document the crisis, express themselves and claim visibility. The ensuing movies weren’t a co-ordinated movement, but a breakthrough of diverse filmmakers loudly taking control and creating a new image for queer audiences eager to see themselves onscreen.

Almost 30 years ago, in a 1992 issue of The Village Voice, film critic B. Ruby Rich looked back at the onslaught of queer independent films released over 1991 and 1992 and coined the label “New Queer Cinema” to describe movies like Edward II, The Hours and Times, Swoon, The Living End and R.S.V.P.

New Queer Cinema didn’t exactly end but disperse, as queer filmmakers like Todd Haynes and Gus Van Sant entered the mainstream and major studios and straight filmmakers started making queer movies. Those later films—Brokeback Mountain, The Kids Are All Right, The Perks of Being a Wallflower and The Dallas Buyers Club—were the first queer movies I saw.

We now live in a great time for queer representation in movies and TV with ample viewing choices. A simple Google search of “queer TV shows” or “queer movies” reveals hundreds of options. Most contemporary LGBTQ2S+ representation depicts queer people as part of the mainstream, which is great: Love, Simon; Schitt’s Creek; Sex Education; One Day at a Time; Brooklyn Nine-Nine; The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina and Never Have I Ever all feature queer people who come out, are accepted by their families and friends and find romantic love, serving as happy role models.

“I don’t just want to see happy role models in assimilationist stories.”

Sometimes, though, I want to relish my difference and see it acknowledged and empowered. I don’t just want to see happy role models in assimilationist stories—I want to see characters who are free to be bad, immoral and complicated. If queerness is fluid and boundary-breaking, I should see it in characters who rebel against consumerist complacency. When I see a world on fire, I’m desperate to see someone who notices it, too. For that type of representation, I go to New Queer Cinema.

New Queer Cinema filmmakers worked outside the mainstream, experimenting with cinematic form, content and genre; their queer revisionism challenged the dominant heteronormative approach to filmmaking and storytelling. Pioneers of the genre did so by centring characters who are marginalized outsiders, unapologetically depicting queer and trans people who are flawed and complicated. There’s the defiance and humour of Marlon Riggs and Cheryl Dunye, the luminous drag queens and trans women in Paris Is Burning, River Phoenix’s sleepy lovesick hustler in My Own Private Idaho and the cynical yet horny romantic duo of The Living End. Even 30 years later, these characters reflect my desires, my depressions and my will to make something of life within a straight world.

Spurred by the AIDS epidemic, New Queer Cinema aimed to defy death and marginalization through onscreen liberation—and that spirit is worth revisiting today.

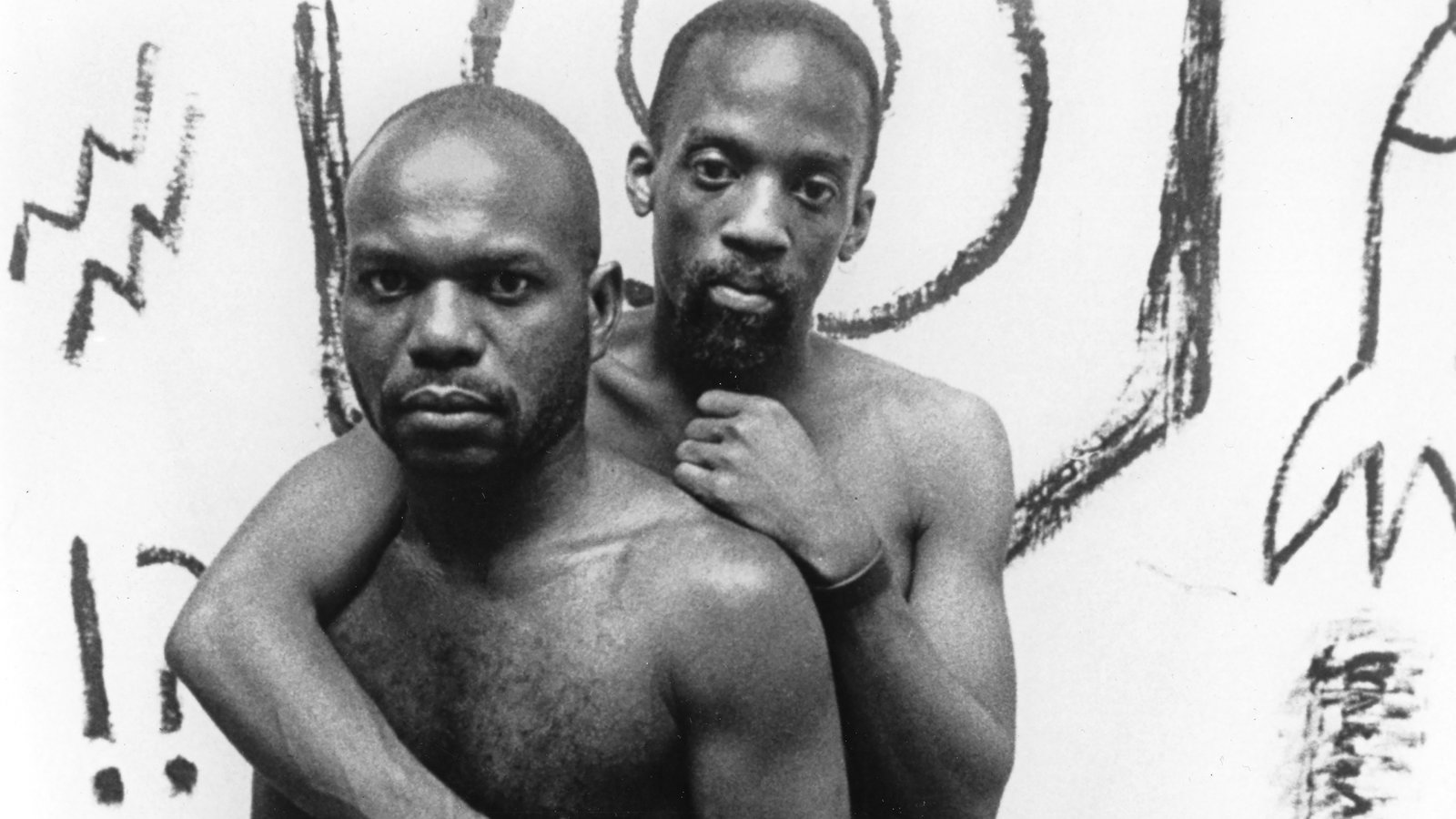

Tongues Untied

Marlon Riggs

Credit: Courtesy Frameline

It’s hard to summarize the “signifyin’” works of Marlon Riggs, an incendiary yet attentive documentarian who redefined pride in Black identities (Signifyin’ Works was the name of Riggs’ production company founded in 1991).

Tongues Untied from 1989 is Riggs’ second film after winning an Emmy Award for Ethnic Notions (1987), a documentary exploring racist Black stereotypes across American history. For Tongues Untied, Riggs combined autobiography, poetry, monologues, music, dance and documentary footage to interrogate what it means to be a Black gay man. It’s an engaging and provocative work, tracking the bigotry Riggs experienced from straight white and Black communities, as well as the white queer community. Riggs created looping soundscapes, repeating slurs over his personal stories to capture the bitter sting of what it’s like to be called hateful words.

Ultimately, Tongues Untied is an empowering film. Riggs claimed relentless and unforgiving pride in his voice and invited Black queer men to share their pride. As Riggs puts it, “Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act.” Indeed, Tongues Untied featured the first gay kiss broadcast on U.S. television.

Naturally, conservatives, like politician Pat Buchanan and president of the American Family Association Rev. Donald E. Wildmon, expressed outrage that the National Endowment of the Arts funded Tongues Untied. Riggs went on a speaking tour where he defended the film and called out racism and homophobia.

After his HIV diagnosis in 1988, Riggs made five more documentaries, ranging from nine to 90 minutes in length: Affirmations, Anthem, Color Adjustment, No Regret, Black Is… Black Ain’t. The latter saw Riggs address the audience from his hospital bed and reflect on his aim to celebrate and unite America’s diverse Black community. Riggs died from AIDS in 1994.

Paris Is Burning

Jennie Livingston

Credit: Courtesy Criterion Collection

Paris Is Burning from 1990 is possibly the most influential queer movie ever made. It immortalized the fleeting NYC drag ball culture of the mid-to-late 1980s, a subculture that inspired Madonna’s “Vogue” and RuPaul’s Drag Race and that’s recreated in Ryan Murphy’s TV series Pose. If reading is fundamental, then so is Paris Is Burning.

Paris Is Burning is an introductory guide to drag balls, explaining competitive categories like banjee realness and executive realness, drag houses and the practice of shade and voguing. The unifying theme is realness, as drag balls offer a world where marginalized gay and trans Black and Latinx people can authentically be themselves and where stardom is all about looking and becoming the role.

As one gay man in the movie says, “It’s like crossing into the looking glass in Wonderland. You go in there and you feel, you feel 100 percent right being gay.”

Paris Is Burning gets its phenomenal power from a cast of glamorous characters who offer insight into the balls and their own struggles in the cruel outside world. The interviews with Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey, Willi Ninja and Venus Xtravaganza are priceless treasures, and the film’s incredible director, Jennie Livingston, caught them on film for us all to see.

Livingston directed a few short films after Paris Is Burning—and recently served as a consulting producer on Pose—but nothing she’s made since has captured its fame and influence.

Poison

Todd Haynes

Credit: Courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

“The whole world is dying of a panicky fright.”

So begins 1991’s Poison, the second film by New Queer Cinema icon Todd Haynes, a surreal horror-inflected movie about the terror of living life as a gay man.

Poison tells three unique stories, each in a different genre and style. The first is a tabloid news documentary investigating a young boy who mysteriously murdered his father before disappearing. Next, a B-movie following a handsome scientist who accidentally drinks an elixir that turns him into a contagious leper. Finally, a roughshod romance between two prisoners in a grimey prison.

Poison expresses homophobia’s nightmarish manifestations through childhood, domestic abuse, disease, ostracization and bullying. It’s a discomforting movie, simultaneously grotesque, erotic and tragic—a brutal reflection of the suffering gay men faced prior to and during the AIDS epidemic. For me, a gay man raised after the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis, Poison underscores the quiet traumas LGBTQ2S+ people endure and which Haynes prods to the surface.

Like Tongues Untied, Poison was also funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and drew ire from conservatives for its scenes of “pornographic anal sex.” But there is nothing pornographic about Poison; in fact, the right-wing panic brought attention to the film and further demonstrated its points against homophobic hysteria.

Haynes maintains his prolific career to this day and I count him as one of my favourite directors. He continued his horror-inflected movies with Safe (1995) and Dark Waters (2019); made a trio of unorthodox musical biopics in Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), Velvet Goldmine (1998) and I’m Not There (2007); and mastered the romantic melodrama with Far from Heaven (2002) and the lesbian classic Carol (2015). I recommend his short film Dottie Gets Spanked (1993).

My Own Private Idaho

Gus Van Sant

Credit: Courtesy of Criterion

My Own Private Idaho from 1991 is New Queer Cinema’s most iconic film, and perhaps the era’s crowning achievement.

My Own Private Idaho stars the beautiful, late River Phoenix as Mike Waters, a narcoleptic hustler who falls asleep whenever he thinks of his tragic childhood and missing mother. Alongside his crush, Scott Favor (Keanu Reeves), a fellow hustler and rebellious heir to a massive fortune, Mike tries to find his mother.

Gus Van Sant’s third feature after the gay romance Male Noche (1986) and layabout crime drama Drugstore Cowboy (1989), My Own Private Idaho is an ambitious cross between Shakespeare’s Henry V and gritty indie movies about outsiders, like Midnight Cowboy (1969) or Streetwise (1984). The storytelling is loose, wandering between rambunctious scenes with Van Sant’s version of Falstaff and artificial asides that comment on masculinity, sexuality and love. Take the moment, for example, when Mike and Scott address each other from the covers of porno magazines or the spellbinding “time-lapse” photography sex scenes. My Own Private Idaho’s best moment is the fireside chat where Mike confesses his love to Scott; Phoenix rewrote the scene, and his delicate soft-spoken performance is profoundly moving.

My Own Private Idaho speaks to the irrepressible longing for home, a feeling surely familiar to many LGBTQ2S+ people who’ve abandoned or been rejected by theirs. It’s a gentle, thoughtful, heartfelt movie that never ceases to amaze in its emotional depth and inventive creativity.

Van Sant has since taken on a fascinating career: He moved into the mainstream with the Nicole Kidman black comedy To Die For (1995) and the Oscar-winning dramas Good Will Hunting (1997) and Milk (2008). But Van Sant never abandoned his experimental streak, making movies like Gerry (2002), Last Days (2005), Paranoid Park (2007) and the bleak minimalist Palme d’Or-winner Elephant (2003).

Young Soul Rebels

Isaac Julien

Credit: Courtesy of isaacjulien.com

Around the same time as New Queer Cinema took off, Black filmmakers also experienced a breakthrough with the likes of Do the Right Thing (1989), Boyz in the Hood (1991) and Daughters of the Dust (1991). That breakthrough did not take place in the U.K., however, where films by Black British filmmakers were met with ignorance and erasure. One exception is filmmaker Isaac Julien, who’s one of New Queer Cinema’s earliest progenitors.

Julien came to prominence with Looking for Langston (1989), an experimental documentary about the Harlem Renaissance that corrects the erasure of Black poet Langston Hughes’ gay identity. Shot in dreamy black and white, Julien constructed a cinematic space from a nightclub that merges past and present. Looking for Langston incorporates poetry from Hughes, James Baldwin and Essex Hemphill with blues and house music, as Black men dressed in period suits dance and make love before police break into the nightclub. Looking for Langston is a lovely movie whose sensuality influenced Moonlight (2016).

In 1991, Julien followed Looking for Langston with a more traditional drama, Young Soul Rebels. Set in London during 1977’s patriotic celebration of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, Julien follows two Black friends trying to make it as radio DJs after the unsettling murder of their mutual gay friend. Despite being set 45 years ago and being made 30 years ago, Young Rebel Souls feels contemporary, with its focus on police violence and intersectionality. Despite the subject matter, Young Rebel Souls finds joyful resistance in dancing, singing, romantic triumph and solidarity.

After making a series of documentaries about Black and queer subjects like Frantz Fanon and Derek Jarman, Julien has stayed in the realm of art installation for the last 20 years where he continues to explore contemporary life through erased histories.

The Living End

Gregg Araki

Credit: Courtesy of Mubi

There’s no feeling quite like seeing your first Gregg Araki film. Araki’s portrayal of queer sexuality, anger, joy and rebellion is so explicit it’s initially startling and shocking, before giving way to gratifying identification.

Upon leaving film school in 1985, Araki shot two ultra-low budget features before breaking through in 1992 with his third film, The Living End. Labelled “an irresponsible movie by Gregg Araki,” The Living End is cinema’s ultimate example of “be gay, do crimes.” It follows two HIV-positive gay men—impulsive hustler Luke and mild-mannered film critic John—as they romantically bond on a “fuck everything” roadtrip, commiting crimes and pondering their mortality.

The Living End thrives on Araki’s passionate instincts, which move from reckless camp to destructive rage. The film is visibly low-budget with its amateurish acting and dialogue, but this enhances the film’s marginalized anger. In an interview reflecting on the AIDS epidemic, Araki said at the time he felt like “I’m literally being exterminated. I’ve been targeted for this genocide.” The Living End builds on that sense of despair and oncoming death, finding in it a nihilistic liberation that’s empowering yet brutally tragic.

Araki continued this nihilistic campy style throughout the 1990s in the aptly named Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, a series of wild and empathetic coming-of-age films about queer teenagers living and loving in a world they see as doomed. Araki never abandoned his unique style and interest in teens as he aged, even as he took on more dramatic topics in Mysterious Skin (2004) and White Bird in a Blizzard (2014), moved to directing episodes of 13 Reasons Why and Riverdale and created his own show featuring sex and aliens called Now Apocalypse (2019).

Blue

Derek Jarman

Credit: Courtesy of Criterion

British director Derek Jarman predates the breakthrough of New Queer Cinema. Jarman started in filmmaking as a production designer on Ken Russell’s ecstatic The Devils (1971) before debuting with Sebastiene (1976), a film about the homoerotic saint’s martyrdom with dialogue in Latin.

Jarman is an eccentric iconoclast who toyed with history by centring queerness and emphasizing that queer marginalization has been a constant battle. The satirical Jubilee (1978) follows a time-travelling Queen Elizabeth I roving around with 1970s punks that sell out to an aged Adolf Hitler. Jarman’s most accessible movie, Caravaggio (1986), saw the Baroque painter in a love triangle with Tilda Swinton and Sean Bean, and used such playful anachronisms as electric lights, car horns and a typewriter.

In 1986, Jarman received an HIV diagnosis and made six films before his death from AIDS in 1994. The Last of England (1988) brought abstracted rage against Britain’s oppressive conservative establishment, while Edward II (1992) showed a historic king sacrificing his reign and life for his male lover. The latter also features ACT UP-style protesters as King Edward’s supporters.

My favourite of Jarman’s movies is his last and least characteristic: Blue, from 1993. Jarman abandoned frenetic imagery and made a movie that’s a single frame of the colour blue, accompanied by spoken monologues, music and audio clips from hospital waiting rooms and Jarman’s seaside home, Prospect Cottage. Jarman was blind when making Blue, and the film’s blue screen forces the viewer into his helpless position as he ruminates on death, listens to his IV drip and imagines what lies behind the sky. Blue is a disarming movie in its startling terror and overpowering clarity. Facing dark blue death, Jarman yearned for art, storytelling and love—I can’t imagine anything more life-affirming.

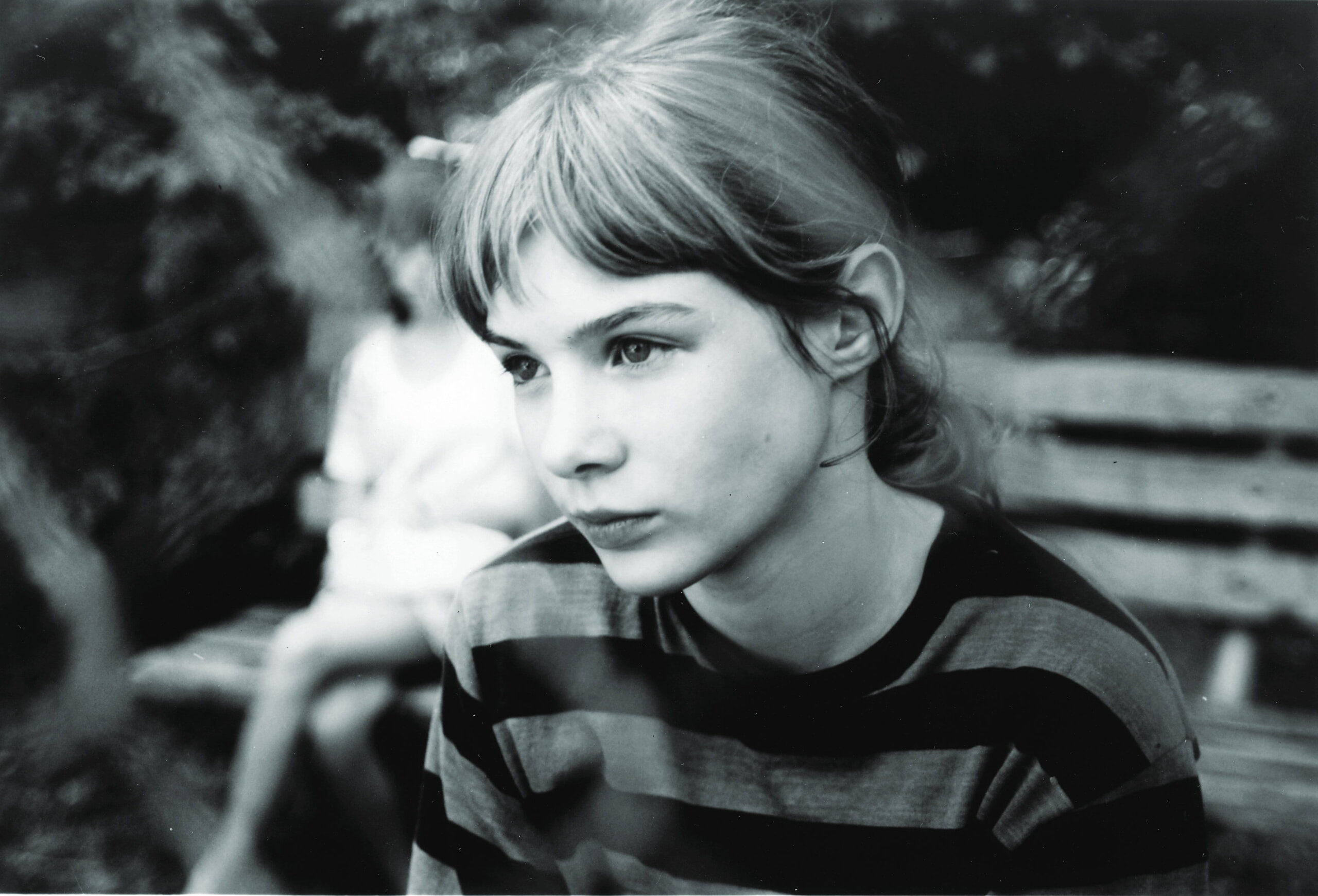

Hide and Seek

Su Friedrich

Credit: Courtesy of Outcast Films

A filmmaker rarely included in discussions of New Queer Cinema is Su Friedrich. Friedrich made short films as early as the late 1970s, but she reached her artistic peak by leaving a joyful, avant-garde feminist stamp on independent cinema of the ’80s and ’90s.

Friedrich directed short documentaries about womanhood, family, lesbian identity and self-realization, often using her own life as a subject. The Ties That Bind (1984) and the masterpiece Sink or Swim (1990) explore Friedrich’s relationship with her mother and father, combining 12mm film fragments, archival footage and text to give the impression of a mind sorting through memories and heartache.

Friedrich’s lesbian films are happier, ranging from the quiet reflectiveness of the religiously themed Damned If You Don’t (1987) to the political rallying cry that is Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire Too (1994).

My favourite of Friedrich’s queer documentaries is Hide and Seek (1996), which combines interviews with 20 lesbians talking about their childhoods with a narrative about a 12-year-old girl, Lou, navigating gender and sexuality in 1960s America while lacking the knowledge to clarify her identity. The thoughtful and funny interviews perfectly illuminate Hide and Seek’s angst-ridden narrative, bringing clarity to young Lou’s alienation and uncomfortable coming-to-terms with puberty. The film ends with The Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love,” giving Lou hope in the promise of future understanding. As someone who’s often reflecting on my long-delayed coming out, this was a cathartic moment of queer reclamation I adored.

Today, Friedrich is a professor of visual arts at Princeton University and continues making short documentaries.

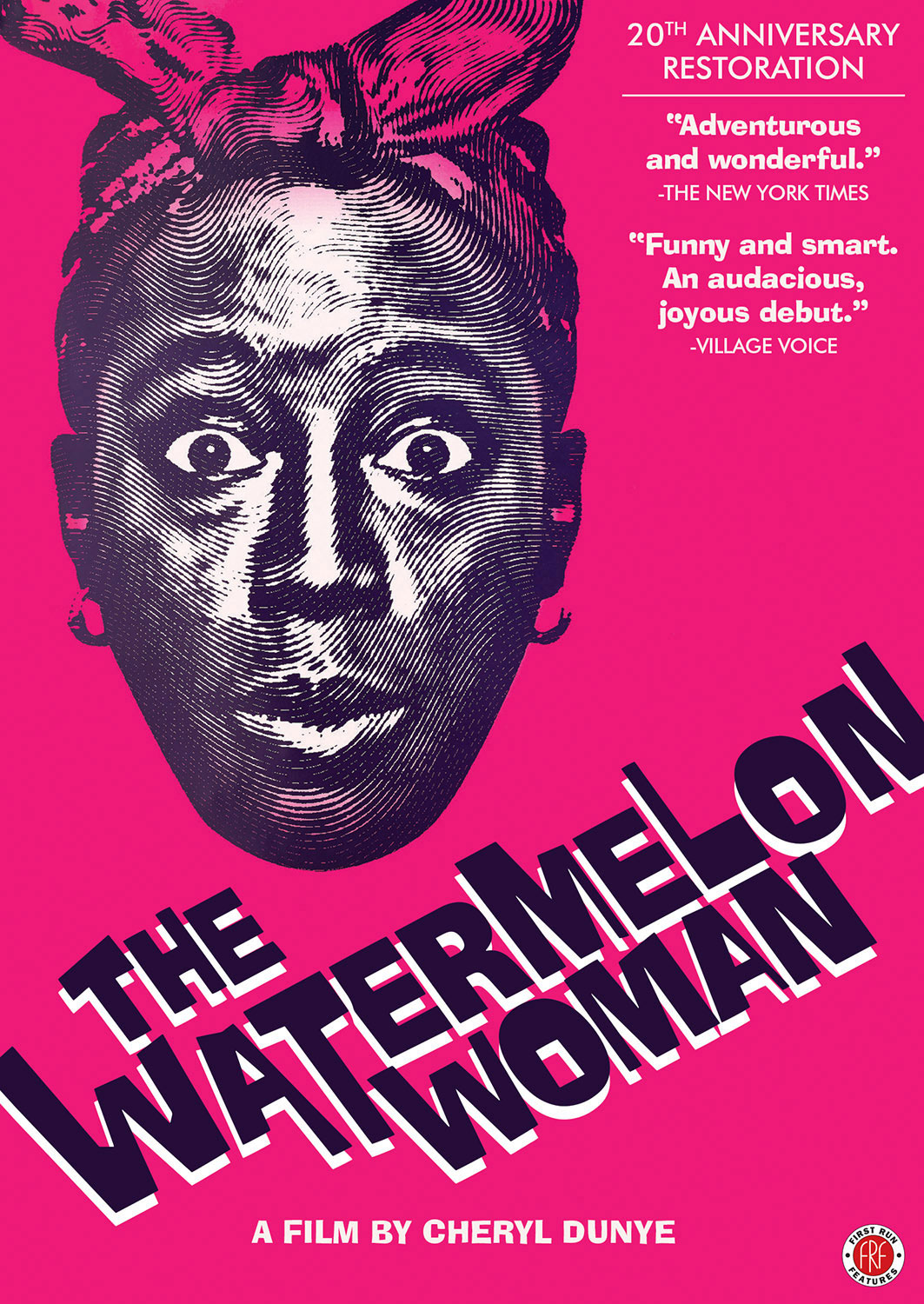

The Watermelon Woman

Cheryl Dunye

Credit: Courtesy First Run Features

If anyone embodies the New Queer Cinema ethos of making one’s own history, it’s Cheryl Dunye.

Dunye started her filmmaking career with six short videos made from 1990 to 1995 she called “Dunyementaries.” Blending fact with fiction, the Dunyementaries chronicled Dunye’s life as a Black lesbian in Philadelphia navigating the complexities of dating and race. The best of these shorts is Janine (1990), a 10-minute monologue where Dunye tells the story of her first crush on an upper middle-class white girl. Janine is an intimate view into racism’s perniciousness and Dunye’s efforts to learn from and put the past behind her.

Dunye ambitiously returned to the past in her landmark debut feature, The Watermelon Woman, in 1996. The Watermelon Woman stars Dunye as herself, a budding filmmaker infatuated with a Black actress from the 1930s credited as “The Watermelon Woman,” who Dunye tries to identify and make a documentary about.

Dunye confronts early Hollywood’s racist representation of Blackness, mocking its absurdity and reclaiming the humanity of talented Black performers. At the same time, Dunye gives much-needed representation by documenting her own life as she dates a white woman and socializes in mid-’90s Philadelphia’s Black lesbian scene. The Watermelon Woman is a funny, colourful and delightfully clever film. It’s the first feature movie directed by an out Black lesbian and it’s about why we need movies focusing on Black lesbian life.

Since The Watermelon Woman, Dunye made two features and a few shorts while also teaching. Since 2017, Dunye has pivoted to television and directed episodes of Queen Sugar, The Chi and Lovecraft Country.

Lilies

John Greyson

Credit: Courtesy of Triptych Media

Canada had its part in New Queer Cinema, too, via filmmakers like Richard Fung, Patricia Rozema, Laurie Lynd and Bruce LaBruce. The most prolific among them—and the one whose work I could access—was John Greyson.

Greyson is New Queer Cinema’s avenger, as many of his films follow queer characters correcting injustices against the LGBTQ2S+ community. In Greyson’s first feature, Pissoir (1989), Sergei Eisenstein, Dorian Gray, Yukio Mishima, Frida Kahlo and Langston Hughes assemble to investigate police crackdowns on gay hookups in Toronto’s washrooms.

Greyson’s resurrection of the dead was put to its most surrealist use in Zero Patience (1993), a musical in which the ghost of Gaëtan Dugas—falsely labelled AIDS’ patient zero—attempts to clear his name. The mix of the film’s subject matter alongside lighthearted pop songs makes Zero Patience jarring. Its bizarre satire of scapegoating is righteous, but feels distant from the emotional realities of AIDS. Between outrageous songs like “Pop-a-Boner” and “Butthole Duet,” Zero Patience’s most moving moments follow an AIDS-afflicted school teacher dealing with stigma and his conflicted feelings on activism.

Greyson would adopt a more sensitive approach for the period-romance in Lilies, from 1996. An adaption of a Michel Marc Bouchard play, Lilies takes place in a men’s prison as the inhabitants force a bishop to watch a confessional play recounting how he unjustly imprisoned an old classmate for murder. As a play-within-a-film, Greyson balances between two worlds: Women are played by men in drag while Greyson fabulously cuts from the mundane prison to the Canadian outdoors to such imaginative settings as a bathtub surrounded by a flooded stage in which the film’s male lovers hold each other. Lilies is an affectionate tale of coming to terms with one’s sexuality through young love and betrayal that’s fanciful and sexy.

Greyson continues making queer narrative and documentary films in Canada, and has taught film theory and production at York University since 2005.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra