Over a crackly line from Montreal, gay choreographer Massimo Agostinelli explains the vital difference between clowning and bouffon: “The audience laughs at the clown. But the bouffon does gags where he’s actually laughing at the audience. They come onto stage and confront society.”

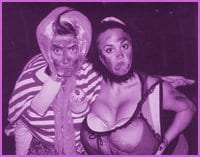

Bouffon, for the uninitiated, is a specialized form of grotesque clowning, based in Medieval theatre and presently enjoying somewhat of a resurgence as a sharp-witted cultural critique. A typical scene features performers in strangely misshaped costumes-tits, asses and bellies hugely emphasized-misbehaving on stage, bringing to life the misfits that they are.

By reversing audience expectations, and never allowing those beyond the floodlights to rest easy, bouffon is the perfect tool for shaking things up, forcing uncomfortable truths to be acknowledged. “The audience represents the society that has rejected these freaks,” Agostinelli explains. When a troupe of greasy, misshapen bouffons take their place on stage, the audience’s laughter gets a cruel edge. What are you laughing at?

Agostinelli’s voice goes up a couple notches as he tries to explain the seriousness of such comedy, its very real criticism of cruelty and hegemony. By presenting audiences with serious frivolity, sincere chaos, “the bouffon becomes a mirror image of the audience itself. The audience is actually laughing at themselves.”

As with most self-reflexive art forms, bouffon is inherently queer. Well, it might be argued that sticking drag queen Justine Tyme on the stage of the Odyssey-she’s signed up to perform in the troupe-is already inherently queer. But there’s more to it than that.

“Sexuality is open,” for the bouffon, says Agostinelli. “They might fuck in the street while having a cup of coffee. That’s the bouffon attitude.”

Since taboo-smashing is on the menu, the bouffons can get away with anything, so long as they stay in character. Their role in society is to raise the consciousness of the audience, to tell them: “Look: this exists. We aren’t leaving. We don’t clean up.”

Sounds a little like a fight we’ve been fighting. “Gay people are bouffons,” insists Agostinelli, “because we are ostracized in society.” He holds that any minority can claim a connection with this theatre.

Bouffon is not new to Vancouver. Grant Heisler, a protégé of clown patron saint, Jacques Le Coq, created a strong bouffon scene here in the early 1980s before moving to Montreal to found his company, Bouffon de Bullion. And last year, Agostinelli (himself a Heisler protégé) brought his own special brand of buffoonery to one of the Fringe Fest’s Granville Island venues to rave reviews. Now, he says, “The tradition lives on! From the pigeon-infested Kiln on Granville Island to the bowels of the Odyssey, we’re baaaaack!”

Actors involved in this year’s bouffon-the culmination of Agostinelli’s 10-day intensive training course immediately prior to the Fringe Fest-have a unique opportunity to get on board a fast-growing craze. “It empowers actors and makes them confident,” notes Agostinelli. “Even as ugly as they are. They are proud of their ugliness, their attributes. There is a common theme of survival.”

The more Agostinelli talks about bouffon, the more I think he’s talking about queer politics. “They take care of each other; they have only each other to rely on.” The team of obscene characters, largely improvising their lines, must work together or perish. “You’re a family; you love each other.”

Which is not to say that Agostinelli predicts smooth sailing. “We have no budget to work with,” he cheerfully blurts out. To boot, since the nature of the beast is organic and improvisational, he doesn’t know what to expect of his performance, entitled “The Coal Daughter’s Miner.” He does know that the bouffon troupe will emerge from a vaguely mysterious catacomb in the Odyssey, supposedly having dug for a year through the club’s underground environs. Their bodies will be filthy from the work, and broken. Our bodies know what it means to be beaten, too. And, again, to survive.

With 25 years of experience, Agostinelli knows something about bouffon survival. The key to success is “based on tons of improvisation. Always working within certain themes-I string those improvs together, creating segues so that things that don’t want to fit together do.” Here’s hoping.

* The Coal Daughter’s Miner runs Sep 9-19 at 8 pm (no show Mon, Sep 13) at the Odyssey, 1251 Howe St. More info: www.bouffon.ca. Tickets: $12 advance/$10 door.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra