If you’re friends with any gay gamers (more affectionately known as gaymers), you may have heard that video game company Nintendo is banning gay marriage . . . or gay relationships, or something.

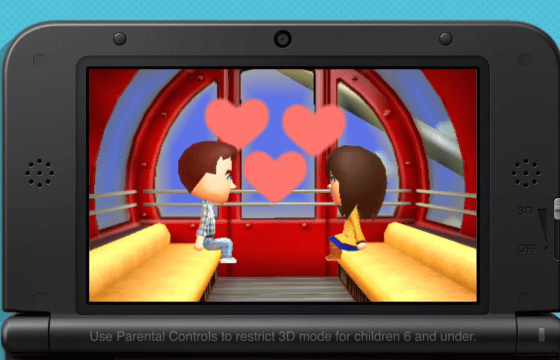

The controversy is around an upcoming casual game called Tomodachi Life. Gay fans of the corporation were outraged when Nintendo announced that same-sex relationships in the game wouldn’t be allowed, and a number of fans and media sites are criticizing Nintendo’s “bans,” saying the company “won’t let you be gay.”

The outrage is unfounded. It’s not that Nintendo won’t let fans be gay or that it’s banned gay relationships. The problem is actually much worse.

Nintendo has never even cared about gay people enough to consider them part of the game. Nintendo doesn’t care about you.

Let’s look at the facts as they actually happened, instead of outraged criticism. Tomodachi Life has already been released in Japan, and when screenshots of same-sex relationships within the games romance mechanics started circulating, North Americans were bemused. This turned out to be a problem with game design and a breakdown of language:

“This occurred because they saw Japanese fans posting game screenshots of male and female Mii characters, where female Mii characters were designed and clothed in such a way that they looked male,” Nintendo told one blogger. “Since these explanations were made in Japanese by the Japanese fans who posted the images, the Japanese people do not have such a misunderstanding.”

Another glitch randomly assigned avatars into existing in-game relationships, which Nintendo said could lead to the appearance of a same-sex relationship. Nintendo has since created a patch and made the following statement: “Same-sex relationships were not possible in the original software.”

My quibble with the critics is a semantic one. It’s not that, as it’s being framed, Nintendo won’t let you be gay or is banning gay relationships or gay marriage. The company actually never even considers it.

One article describes:

“Video games, like other forms of media, have long struggled with representation, especially when it comes to LGBT characters. With a few notable exceptions — including recent critical darlings Gone Home and The Last of Us — narrative-driven games are primarily home to characters who are straight, white, and male. Simulations like Tomodachi Life can be an exception to this rule, letting you build characters that look and act just like you do. The best-selling Sims 3 series allowed for same-sex relationships — you could flirt, fall in love, and even marry characters of the same gender. It may have been released in 2009, but The Sims 3 was more progressive than a Nintendo game in 2014.”

Aside from being wrong — The Sims, released in 2000, allowed limited same-sex relationships, and The Sims 2, released in 2004, allowed relationships equal to heterosexual ones — I think this kind of argument misses the point, especially in relation to life sim games like The Sims series and Tomodachi Life. The token of being allowed to engage in same-sex relationships or marriage in a game, or the surface inclusion of LGBT characters in any kind of media, means nothing if the people who create media don’t back it up by addressing issues of inclusion and representation in the industry.

Take, for example, The Sims. Created by EA Games, it was “one of the earliest mainstream video games to include actionable same-sex relationships when it launched in 2000.” The arbitrariness of inclusion of this “optional” mechanic, or rather the way one developer snuck it in, doesn’t say much for the industry as a whole.

On the other hand, the exploration of same-sex relationships in sci-fi action series Mass Effect, a Canadian developer owned by EA, means a little bit more. As one Kotaku article notes, “In the video game adventures of Commander Shepard, being a gay man was neither a matter of biology nor choice. It was a matter of programming.” While certainly not perfect, relationships in the games were crafted with care, with a fair amount of emotional depth, and even though the developers said that it surprised them people thought it was a big deal, it is a big deal.

Asking for same-sex marriage or gay relationships in games is asking for too little. I’ve been playing Nintendo games since I was three years old, and off the top of my head I cannot once recall a single Nintendo game that included a queer or trans character beyond innuendo or stereotype.

Like many other media makers, it isn’t that Nintendo has done something hateful to the gay community. The problem is it hasn’t done anything at all.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra