Canadian director Laurie Lynd’s new documentary, Killing Patient Zero, takes a hard look at the first years of the HIV epidemic and its terrible cultural and political consequences. In particular, the film examines the abuse suffered by, as well as the fate of, Gaëtan Dugas, a gay Canadian air steward who was mislabelled “patient zero” in journalist Randy Shilts’ bestselling 1987 book, And the Band Played On. Shilts characterized Dugas as being both sexually reckless and the primary source of HIV infection in the US. But Dugas was just one of a handful of early victims of the AIDS crisis — he died in 1984 at the age of 31.

Packed with archival photographs and video footage, heartbreaking interviews with Dugas’ friends and vintage (often alarmingly homophobic) media coverage, Killing Patient Zero asks the viewer to remember the true horror of the era and the mysterious disease that marred it, and then to ponder how queer communities regard that era now. What did we learn? What have we forgotten?

Featuring interviews with filmmaker John Greyson (who debunked and mocked the “patient zero” theory with his 1993 classic Zero Patience), journalist Matthew Hays, writer Fran Lebowitz and about 40 seconds with me (blink and you’ll miss it), the film unfolds like a vigorous but loving dinner table heart-to-heart.

If you were alive during the first years of HIV’s arrival, the forgotten and overlooked footage — frantic public meetings, lurid and sensational media coverage — will spark many memories, good and bad. Killing Patient Zero is both an argument for understanding and an important historical document.

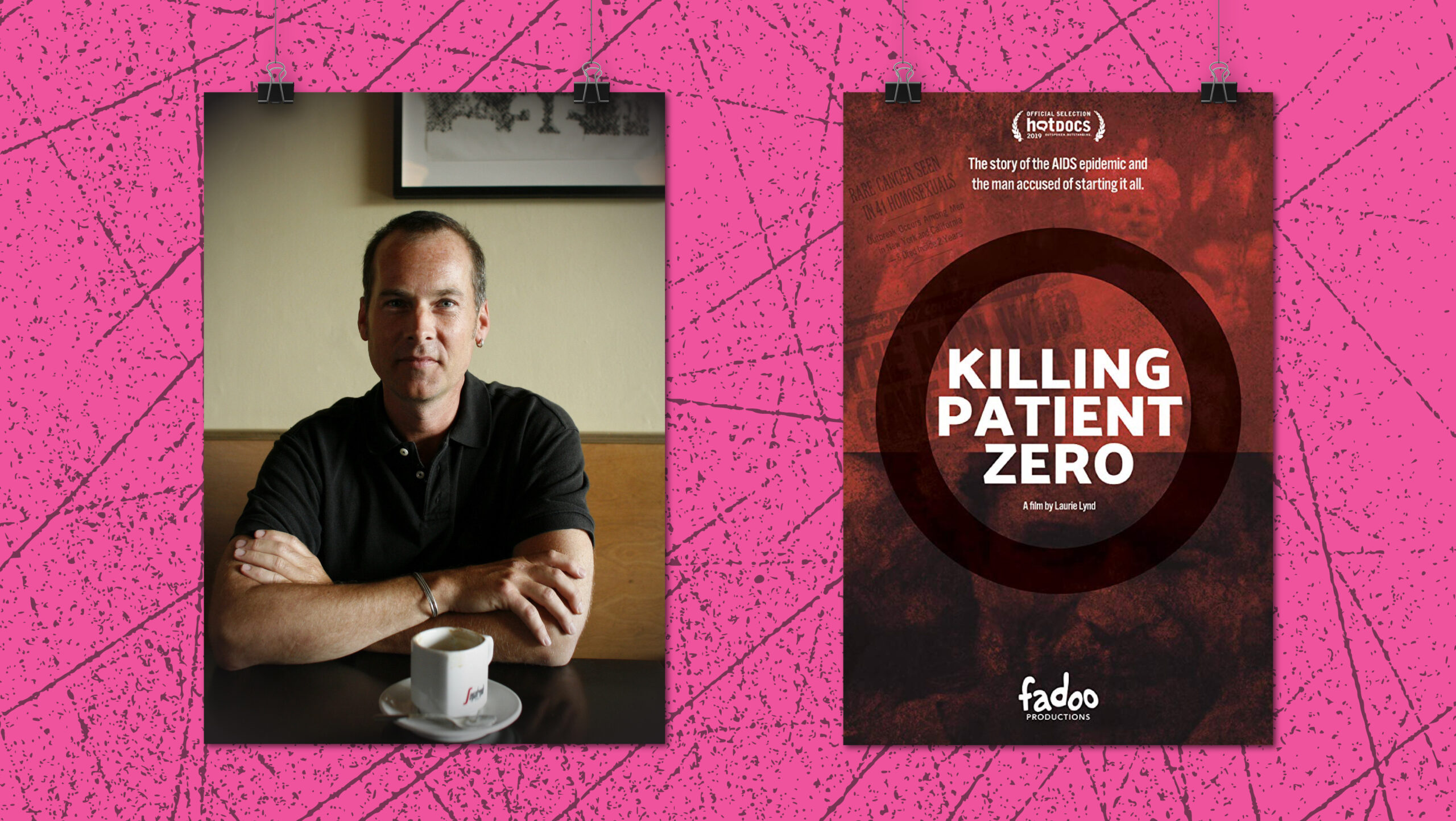

I sat down with Lynd on the weekend of his 60th birthday to talk about the film.

How did you decide which voices to include and when to include them in the film?

Many of the names came naturally from the book on which the film is based, Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic by Richard McKay. Many other names came from And the Band Played On. We researched people who knew and worked with both Shilts and Dugas. My original plan for the film was to make it a dual biography of these two gay men whose lives crashed into each other (albeit posthumously for Dugas). But the first cut of the film was so long that it became immediately clear Shilts’ biography wouldn’t fit. That said, we are now planning to do a feature doc on him.

I wanted to speak with gay men and women who lived through this time period. From the beginning I knew I wanted to make the film a portrait of what it was like growing up gay in the 1970s and ’80s, about what society was telling us about being gay and underline the timing of the AIDS epidemic — only a decade into true gay liberation. I wanted to tell that part of the story so a contemporary audience would understand both Shilts’ and Dugas’ actions — but also because I feel that this is a forgotten story that needs to be told. And then told again. And again.

No queer person will ever speak to me again if I do not ask what Fran Lebowitz was like. Can we have an OMG moment here?

Okay, OMG, I couldn’t believe Fran Lebowitz agreed to be interviewed! I have been a fan of hers since high school in the ’70s, when my gay pals and I were all reading Social Studies and Metropolitan Life.

I knew I wanted to interview Fran when I read her remark about how the AIDS crisis not only lost us countless artists, but it also lost us an entire audience: “If you removed all of the homosexuals and homosexual influence from what is generally regarded as American culture,you would be pretty much left with Let’s Make a Deal.” I thought hers would be an interesting perspective, having been on the front lines of AIDS in New York City. I also thought it would be good for such a dark story to have some humour — which, to me, is the very essence of “gay.”

Fran L doesn’t have a cell phone or a computer, God bless her, and so all communication was done through her assistant. I wrote a letter to Fran explaining why I’d love her to participate, and weeks and weeks later we heard back. OMG.

I didn’t really believe she would show up till she was there. Originally, I’d asked for a two-hour interview but was told that day by the assistant that I’d only have an hour. I found that I only needed 45 minutes for the interview, so thorough, far-ranging and delightful were her answers. There are bits that killed me not to include in the final film, such as her comment on Elizabeth Taylor being so prominent in drawing attention to AIDS: “Her heterosexual credentials were impeccable — she was married, what, 65 times?”

What can we learn about how AIDS unfolded in the media then, and how can we put that knowledge to use now?

I think the greatest lesson from how AIDS was covered by the mainstream media back then is one of bias, of prejudice and ignorance. The New York Times did something like five articles in the six years preceding publication of And the Band Plays On . . . That reveals how prejudice against homosexuals limited what could have been life-saving attention paid to the emerging plague.

The lesson is one of not letting bias and prejudice inform what’s considered to be news — something I fear that can never be fully learned, and, in some ways, is more deeply entrenched in our era of citizen journalism; much of what ends up being disseminated by non-legacy media is pure bias.

Dugas’ family still will not talk to the media. I can’t blame them, and you handle that truth very respectfully. How, then, did you find his old friends, and how did you create a space for them to speak freely?

Most of the people we interviewed who knew Dugas were also in Zero Patience. There are one or two — most notably Gaetane Urevig, a former flight attendant and loving friend of Dugas’ — whom my researchers found. It was interesting, and not surprising, that there were several people who knew Gaëtan who declined to be interviewed — they were so fatigued by the horror and the story put upon Dugas, I’m guessing, and perhaps they didn’t want to give the story currency again.

I sympathize with that reaction, as I do regarding the family’s decision not to participate. It remains a concern of mine that my film will rekindle, for Dugas’ family and friends, the difficult time when the patient zero story was first erroneously circulated in 1987. My fervent hope is that the greater good, in rehabilitating his name, will justify the story’s re-emergence.

This film is heartbreaking and blunt. What was the emotional impact for you?

An apt question: it was heartbreaking and quite emotionally devastating to live in the world of this story for the intense year and a half it took to create the film. Much of it was triggering for me: as an out gay man who lived through — and miraculously survived — the plague years, I was constantly surprised to realize how much I’d (perhaps deliberately) forgotten about those horrible times.

I felt — and feel — it has been a great honour for me to be able to tell my version of this story. As one can tell from the film, not only do I want to debunk, forever, the patient zero story, but I also want to tell a contemporary audience the horrors of what homophobia wrought on my people before and during the AIDS crisis. It still astonishes me that much of this seems to be forgotten.

I don’t think I’ve ever felt as passionately engaged with my work as I have been on Killing Patient Zero. But it definitely took a toll — one that isn’t the same, of course, as those whose daily lives are touched by HIV, but one that festers. It’s hard reacquainting oneself with the virulent hatred that was, and very much still is, out there toward homosexuals. I fear that the ensuing internalized homophobia, which we all battle, is an intergenerational trauma that will be with us for a long, long time, regardless of the wonderful civil liberties we now enjoy in the west.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra