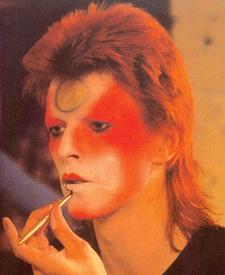

In 1972, a slender young man from the South London suburb of Bromley, who had preternaturally opalescent skin and spiky, iridescent orange hair that looked like the mantle of a cockatoo stuck by lightning, told the music magazine Melody Maker, “I’m gay and always have been, even when I was David Jones.”

That was a dangerous statement to make in those days, and potential rock ‘n’ roll suicide. Yet it propelled David Bowie, who had changed his last name so as not to be confused with Davey Jones of The Monkees, far beyond other rising stars to the rarefied stratosphere of superstardom.

He later said that it was probably the smartest thing he ever told the press. It certainly didn’t hurt the publicity for Bowie’s fourth and breakthrough album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars, which Out.com recently ranked number one on a list of the 100 “gayest” albums of all time.

Most pop stars and bands that came of age after the mid-1970s have benefited from and incorporated aspects of Bowie’s explorations of gender, image, musical genres, multimedia, technology and business, often without knowing it.

Glam, punk, new wave, new romantic, electronica, metal: he set the stage for pop music culture today, wearing makeup, extravagant costumes and massive platform boots. Bette Midler, Bowie’s contemporary, wasn’t just whistling Dixie when she said, “Give a girl the right shoe and she’ll conquer the world.”

I was nuts about both Bowie and Midler when I was in high school in the mid-’70s. I even did a project about “Glitter” for my Grade 10 Social Studies class, in the spring of 1974. I cut out the side of a large cardboard box, wrapped it in shiny aluminum foil, decorated it with sequins and rhinestones, and glued newspaper and magazine clippings of Midler and Bowie onto it.

Midler famously got her start singing in the tubs, at New York’s Continental Baths. Bowie was influenced big time by his relationships with gay artists, performers and designers, not to mention his association with the ambisexual denizens of Andy Warhol’s Factory scene. I set up an easel in front of the blackboard, picked up a pointer and presented my lecture in the hope that I could get my fellow classmates on trend. I got an A.

Bowie provided the soundtrack when I was coming out, a soundtrack that nearly drove my parents mad since the stereo was in the living room. “Oh you pretty things, don’t you know you’re driving your fathers and mothers insane,” goes a lyric from a track on the 1971 album Hunky Dory, which has a cover featuring a blonde-haired Bowie looking like some glamourpuss from Hollywood’s heyday: Katherine Hepburn, say, or Greta Garbo. My mother concurred.

“You look cheap,” she said one night as I was stepping out to go to a high school dance. “You’re not going to take the bus dressed like that?” She wasn’t angry. She was bemused.

It was autumn 1974. I was in Grade 11. I didn’t know what my mother was talking about.

Cheap? Hardly. The sea foam, high-waisted satin pants, blue and white platform shoes with six-inch heels, hibiscus print shirt and armload of bangles had set me back a few weekends of wages from my part-time job as a dishwasher at Trinity Lodge, a Baptist retirement home.

Maybe it was the makeup. Back then, no suburban Vancouver mom in her right mind wanted her boy flinging himself onto the transit system with a face full of slap, looking for all the world like a hooker from outer space.

Which was kind of the point.

My favourite song of the moment was “Rebel, Rebel” off the album Diamond Dogs. “You’ve got your mother in a whirl; she’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl,” Bowie sang to a catchy pop beat. I proudly boarded the Dunbar bus, swaggered down the aisle like the glamorous thing I was, and headed over to my 19-year-old boyfriend’s house. Ross was my date for the dance at University Hill Secondary.

Another time, my mother spied a poster on my bedroom wall of the cover of the 1975 album Young Americans. Bowie had shed the trappings of glam and was doing a postmodern take on Frank Sinatra —if Sinatra wore blush —transforming himself from Ziggy Stardust into The Thin White Duke.

My mother laughed and rolled her eyes. “Some people put up pictures of Jesus Christ, other people put up rock stars.”

I rolled my eyes right back at her. “I’d rather put up a rock star,” I said.

When everyone else was out of the house, I’d turn on the stereo, crank up the volume and lip sync to Fame in front of a mirror.

Like most kids, pop culture not politics influenced my self-identity and self-confidence, and no one in pop culture in the 1970s was more influential to a kid who did not fit in —and didn’t want to —than David Bowie.

“I think I liked Bowie because I felt like an outsider,” says Vernard Goud, who moved here from Holland in the early 1980s and has seen the singer in concert a dozen times. “He was about being new and cutting edge, and still is, and I want to bring that [sensibility] back into the 21st century.”

Goud is producing the second annual Bowie Glamball at Celebrities nightclub on Feb 5. Glamball is based partly on New York’s very popular Bowie Ball, which has become a template for similar events popping up in cities across North America, and the Bowie Nights that were a regular feature at Vancouver’s legendary Luv-A-Fair in the ’80s.

“Without Bowie, there wouldn’t have been a Luv-A-Fair as we knew it. No way. He was the new wave ringleader, and new romantic too.”

The event includes art installations, vintage Bowie and related music from the last three decades, door prizes and a Bowie tribute band. Goud hopes it will be a nice change from the same old same old.

“Why would you stop searching for cool, new things?” Goud asks, as we both reflect on Bowie’s constant and consistent engagement with and support of musicians and artists who challenge the mainstream.

In fact, a new generation is searching for cool, new things, concurrent with a widespread resurgence of interest in Bowie in recent years. Just look at 22-year-old Lady Gaga, the disco diva du jour, who sports a blue lightning bolt under one eye in the video for the single “Just Dance.” This is a reference to the zig-zag adorning Bowie’s visage on the cover of 1973’s Aladdin Sane.

Aladdin Sane was the second “Ziggy” album before the singer killed off his androgynous persona in the last concert of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars at London’s Hammersmith Theatre on Jul 3, 1973.

That was also my 15th birthday, the summer I came out and had sex for the first time.

Earlier that spring, I had gone to my first rock concert with a friend. Lou Reed was touring to promote his Transformer LP, which included the hit song Walk on The Wild Side, a soulful R&B ballad about Andy Warhol’s Superstars, the drag queens Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn and Jamie Curtis. Bowie produced the record. We were awestruck. Everywhere we looked we saw queens dolled up in satin jumpsuits, platform shoes, sequins and rhinestones.

Of course, Bowie and Reed were and are both primarily straight, if at one point easily diverted. Who cares? Goud is straight too, like many of the guys I knew and know who were or are into Bowie. He gave them all licence to express themselves just as he gave me licence to express myself.

In Grade 12, just before grad, I took a group of my straight high school friends to Faces, a club that defined gay Vancouver in the 1970s. They played a lot of Bowie that night, mainly from Young Americans and Station to Station. We all danced together, and couldn’t have cared less about who was fucking whom, which is the way it should be. And, increasingly, the way it is.

We were the artsy kids, the stoners, the rockers, the smartypants, the fags and the dykes: the kids who grew up to be interesting people. Bowie was just one of many burgeoning cultural influences that made it such an exciting time to be young, but he was among the most important. His energy and vision, which few pop artists before, after or since can claim, remain relevant today.

When I was growing up, everybody thought I was into Bowie because of the gay thing. That was only part of it. He appealed to my sense of adventure and wonder, and he appealed to my intelligence. Bowie’s albums helped give me courage. They gave courage to a generation of kids who, like me, felt like misfits.

There is one thing I have wanted to say for a long, long time: I came out as a gay person when I was a teenager but I also came out as a man. Bowie was more than one of my gay role models. He helped me define myself as a man. He still does.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra