As a gay man, I have always wondered how to work with hip hop. Until recently, I didn’t like hip hop, mostly because of the homophobia. But its presence in the culture is a constant. Its rising from a minority tongue to a pop lingua franca has meant ignoring it almost means not being able to speak generationally.

Examples of how hip hop hates fags have abounded from the beginning. “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang, often called the first rap single, includes the lines: “Superman/ I said/ He’s a fairy/ I do suppose/ Flyin’ through the air in pantyhose.”

The homophobia continued unabated. Public Enemy gave an interview to a London paper in 1988, saying, “There’s no place for gays. When God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, it was for that sort of behaviour.”

Common, an MC with equally progressive politics, cast derision on us a decade later. “In a circle of faggots your name is mentioned.”

And I have yet to mention Ice Cube or Eminem’s odes to fagbashing/murdering or 50 Cent’s copious use of the six-letter F-word or Tupac’s or Biggie’s or even Jay Z’s continued, systematic and explicit homo hatred.

I was sorting out the implications of this last year because I was worried my dislike of hip hop was a racist/white privilege thing.

But the homophobia kept coming up — even though Kanye West told everyone to play nice, and I finally heard artists like Deep Dickollective, who released a CD in 2005 emblazoned with a moody portrait of James Baldwin and titled BourgieBohoPostPomoAfroHomo.

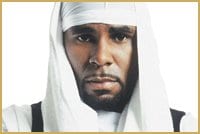

Then I discovered R Kelly’s epic video and musical opus Trapped In The Closet and everything changed for me.

Kelly’s creation solved one of the intractable problems of gay politics and hip hop, offering the queerest text ever charted in the genre (aside from Lil’ Kim’s psalm to oral pleasures, “How Many Licks,” which is only queer because it’s easily transferable.)

Kelly’s opus got radio play. He debuted chapters of Trapped at the Grammys and the MTV Music Video Awards, and the whole thing sold millions and lasted for eons.

The songs and the corresponding videos lasted past the summer season, where most pop hits lived and died like mayflies. I danced to it in clubs, sang along to it on the radio and bought the DVD with all 12 chapters early in 2006.

For me, Kelly’s opus is gay because it features two middle-class, Christian men desiring each other. But it’s queer for its conflation of black and queer camp, plus its subversion of ubiquitous domestic melodrama.

Trapped In The Closet’s interlinked music videos centre on a network of sex between common acquaintances.

It opens with Sylvester (played by Kelly) making love to Cathy until her husband Chuck unexpectedly comes home. Sylvester hides from Chuck in Cathy’s closet.

Then Sylvester’s cell phone rings, exposing Kelly in the closet and pushing him out. The three fight and Chuck reveals that he has a lover just like Cathy. And his lover is a man, too, named Rufus. (So now we have two people out of the closet.)

Sylvester then calls home and hears another man on the other end of the line. He rushes home and is stopped by a cop named James. When Sylvester finally gets home, the male voice turns out to be his brother-in-law, just released from prison.

Sylvester and his wife Gwendolyn make love so passionately and with so much purpose that Kelly says it’s like sex “meant for having a baby.”

Then Sylvester finds a condom wrapper in his bed, and he and Gwendolyn fight. Gwendolyn, it turns out, is having an affair with the cop.

Afraid for her safety, James the cop suddenly shows up at the house. Twan, the brother, comes home at the same time. There is some gunplay. Twan gets shot but it’s a flesh wound. James goes back home to his wife Bridget.

Bridget is acting suspicious. She and James fight until we find out she is carrying on with a midget stripper in a purple pimp suit, who is the father of her baby.

Bridget calls Gwendolyn for help against the cop, and both Sylvester and Twan appear. Sylvester knows the midget from the clubs.

The show ends ambiguously with Gwendolyn calling Cathy, and Cathy confessing her affair with Sylvester — and, of course, finding out that Rufus is the deacon to Pastor Chuck.

Explaining the plot doesn’t explain how fucking camp it is. Camp in the sense of Sontag, camp in the sense of “no more wire hangers,” camp like Lee Bowery delivering children at Wigstock, camp like early John Waters and late Douglas Sirk.

This is brilliant camp, both queer and black, where the world turns upside down and mocks the rich and powerful.

Hip hop often features piss takes on race, mocking moribund status symbols like Tommy Hilfiger. Kelly’s hip-hopera is no different, transforming suburban McMansions into afrocentric temples, and taking trenchant digs at Mama On The Couch plays, Jay Z’s paranoia, and the politics of black masculinity.

As for its gay camp, straight folk are uncontrollably unstable. Here, the hypocrisy of their power is laid clean. By having adultery cross class and race lines (Bridget is white, James is working class), and by adding such clowning as midgets and slapstick, Kelly mocks marriage. It’s the gay radical’s point of view: Why would you want to do a silly thing like that?

Hip hop also often features a certain hyper-masculinity. Or in the words of critic Scott Seward: “Hyper-masculine? For sure. But it should be noted that rap [is] the gayest popular music genre on earth! Oh sure, cabaret and show tunes in retrospect, and house music and disco in spirit, but for attitude, love of jewellery, revenge fantasies and leather pants nothing beats [rap].”

In Trapped In The Closet, Kelly turns the standard homophobia of hip hop inside out. Most viewers would assume that the most twisted act in this whole thing is Rufus and Chuck’s love. It’s not. The only time Kelly mentions how “twisted” something is he’s referring to the midget.

I am not claiming that Kelly is gay, because he obviously is not. Though he does have that sensitive thug thing that makes one hard, similar to James Dean, early Marlon Brando and anyone who has shown up in a Bruce La Bruce movie. It’s a good look.

This entire high camp works better in context. The camp melodrama, a high octane reworking of Peyton Place without moral condemnation, has mushroomed in the last few years.

Six Feet Under, created by a gay liberal, took itself too seriously, but had one of the few decent out men on television. On its heels came Desperate Housewives, created by a gay Republican as a tribute to his mother. Critics have rewarded that show as a comedy, but its status is floating and ambiguous.

Then there was Mr And Mrs Smith, who took the violence under the surface of these two shows and highly ritualized it, making the crisis of heterosexual masculinity a matter of literal life and death.

All of these examples are mostly white, with the token Latina and African-American character.

R Kelly’ s Trapped In The Closet comes at the end of this — and is as strange any of the other dramas that have come around.

But in an African-American context, it pushes the text to other communities. Its exaggerations work real issues of race and gender — especially for mainstream gay audiences who might otherwise dismiss hip hop as too problematic to bother with.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra