Joel Gibb is coming at me and he’s really wet. Hosanna on high, it’s my lucky day. A flash of summer rain has soaked him to the skin; he shakes off like a salty dog. We decide to go back to my place. One look into his big watery eyes and bee-stung lips and I’m so smitten I forget where I live.

Being around The Hidden Cameras’ front man has always made me feel a bit dreamy, like I’m back in high school. Indeed, Toronto incubates a bevy of thirtysomething fey boys in the arts – from DJ Will Munro to painter Paul P to video artist Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay. Which begs the question: Is perpetual adolescence an idealized artistic state, one in which the sad and socially conservative idea of accepting fate is rejected in favour of constant curiosity, love and change?

In Toronto’s “Sibling Society” – a self-imposed isolationism wherein teenage hormones rule aesthetics – such an ethos has been the foundation of the city’s most impressive cultural output. Think West Wing’s groundbreaking show Dead Teenagers. Think Vazaleen. Think Art System. In the high of such Peter Pan pixie dust, it seems inconceivable that agitator-artist Jubal Brown may one day break a hip or that electro-punk Peaches will in-evitably hit menopause.

At the centre of this litter of kittens is the charismatic Gibb. Of course, much of his charm comes from feigned innocence. He’s adorable. A living, loveable Muppet who shuffles around like he’s slipped off the page of a Roald Dahl book. The allure of the impish tramp is irresistible. Recall Dahl’s hard-knock hero James – an elephant tramples his parents, leaving him in the hands of cruel and crusty aunts. Despite this, the sprightly orphan goes on to captain a very large flying peach.

The Hidden Cameras have saved and salvaged sensitive souls on both sides of the Atlantic, harnessing a fan base that demonstrates an almost evangelical devotion. Gibb himself dubs the project “gay church folk music,” clarifying gay as in happy and church referring to his gospel influence.

“People always ask me why I write gay songs,” he says, rolling his eyes. “You’re supposed to write about what you know, what you care about. How can people ask that question? I mean, what age are we in? Men have been writing songs about their ladies forever.”

Gibb goes on to parody European journalists who say, “I can’t believe you label your music as gay. Don’t you think you’re sacrificing a demographic of fans you could otherwise have?” We each raise an eyebrow and start to giggle. He guffaws, “I’d tell them, ‘Do you think I’d care if some straight guys don’t like my band because I sing about loving a guy?'”

That isn’t to say that straight couples don’t get horny at Cameras shows. I’ve ogled straight and gay couples making out side by side at Cameras shows. Gibb maintains that if the music is good, anyone one can tap into the vibe. His typically drowsy NyQuil demeanour shifts into a double espresso rant as he describes the mainstreaming of Nirvana. “Kurt Cobain, who was such an outsider figure, became the most mainstream figure. Even in football, jocks were singing ‘Rape Me,’ thinking it was funny. I don’t think Cobain intended that. But he made such appealing music – and jocks could tap into that anger.”

It’s obvious that Gibb disdains such misappropriation. “In order to access The Hidden Cameras, you have to pass through challenging barriers,” he points out. “So if it makes some straight guy upset, then good, that weeds people out.” His saccharine melodies do tend to lull the uninitiated into a false sense of security. Then out of nowhere, a lyric like “I want another enema” bursts the bubble of what you assume is familiar. When Gibb’s personal pop vocabulary meets his literary devices, he creates tensions that trump the sad state of passive listening. Much like a Sunday school preacher thumping the gospel on the heads of dozing babes to wake them up.

The first night I saw the Toronto-based band assembled happened to be their maiden voyage, in December of 2000. Artists Paul P and Karen Azoulay invited Gibb to do something for their relatively new gallery West Wing, on Queen St W. I’d dropped in to see the work of a painter friend, unaware there’d even be a band playing, so inauspicious was their beginning. At first sight of this cherubic, milk-fed motley crew, I thought I’d mistakenly walked in on the audio-visual club meeting of the local middle school. Now, when they break out mock manifestos like the beloved “Ban Marriage,” the liturgical transformation of the little rascals into maladjusted mini-martyrs is glorious beatification, full stop.

The Hidden Cameras’ much anticipated sophomore album, Mississauga Goddam will be launched at Trinity- St Paul’s on Fri, Jul 23. More initiation rite than mere dropping-in-for-the-last-set-style concert going, attending a live Cameras show is, in essence, a pledge to a louche fraternity-meets-glee club. The most compelling aspect of the band’s messy growth spurts is that it happens in full view of their fans. You don’t view the show as much as live it, like a love affair that taught you the best things about yourself.

With male go-go dancers in ski masks and jockstraps, a Cameras show is part fairy jamboree, part flesh trade. When you’re addicted and miss one, a junkie’s remorse sets in. I caught a cold just before their Animals Of Prey show last year. I lay at home bedridden and sallow, like a plucky vampire who’s discovered there are no virgins coming for the weekend.

Gibb, 27, grew up in Mississauga, amidst the power lines and the hiccup of townhouses lining the landscape. His pensive, nostalgic blend of literate, lampoon pop examines sexual longing, social lethargy and isolation.

Nuances are revealed through a lattice of instrumentation; a witty perversity counters the candy sound. On “That’s When The Ceremony Starts,” Gibb’s varnished vocals are offset by matte-finish strings and perky glockenspiel. Clappable melodies and adolescent antics aside, it’s the incisive narrative writing that rescues the band from the too cute syndrome. Packed with bouncy rhythms and buoyant harmonies, when the band hits the chorus of “I Believe In The Good Of Life” they explode like a kindergarten rhythm section on crack.

Gibb’s thesis poses that even if your thrush clears up and your crabs crawl off, the boy-addicted body still betrays. His sonic landscape is littered with failing bodies, fallible and frail. Lust is an idle pinch, a lazy bite. With such limber anatomies of malaise as “Music Is My Boyfriend,” Gibb’s wallflower wit hints at the wilted salad bar of gay suburban natural selection. The social Darwinism of Gibb’s universe privileges the oxymoronic man: the balding preteen, the jock with a woman’s thighs. It’s such images that suspend me in milk and honey, which I find most beautiful and beguiling.

With such hits as “Golden Streams” – Gibb is perhaps the only musician who can sing about pee with such a puritanical straight face – many songs could be shelved in the young adult section.

Just as many could be classified as an ode to a boy. I ask him pointblank if he’s boy crazy. To my surprise, he actually blushes. Moreover, he resists spinning off an affected readymade retort. He pauses, then carefully sighs, “I can’t help it. I was practically celibate in high school; I never got any action. But lately it’s been quite good.” It’s a pretty modest response, considering this is the boy who has brought new meaning to the concept of “boy pop idol.”

Since The Hidden Cameras’ debut

album The Smell Of Our Own, the wunderkinds have played cathedrals, porn cinemas and posh charity balls. After touring North America and Europe to critical acclaim, the band-cum-socialist-commune faced the challenge of hitting the big time, signing with Geoff Travis’ legendary UK label, Rough Trade. Travis is credited with discovering The Smiths, and was an early proponent of the practiced guilelessness of Belle And Sebastian. If the impresario has his way, the Cameras will be top of the pops by Christmas.

Despite the veritable subculture that has exploded around the band, Gibb shies away from such sticky monikers as Pied Piper Of The Dispossessed or Minstrel Master Of The Maligned. “One of the reasons I love Toronto is because of all the interdisciplinary artists living here,” he says. “I don’t see myself as the leader of anything. It all happens because we all live here.”

In the genesis of The Hidden Cameras, Gibb wrote all instrumental arrangements and lyrics, then taught friends to play the parts. Despite the phenom-factor of the band’s meteoric rise, Gibb remains committed to hand-painting invitations and handbills. He still makes the collages and overhead drawings that accompany live performances, remaining monomaniacal over every aspect of the band. He’s an egotist in the best possible way, self- centred in the way that gets the job done – as art by consensus or committee is often boring and incoherent. The music stays bright and tight because despite their stance on inclusion, the collective acknowledges there must be a bandleader.

In a time when boasting an absurd amount of people onstage remains de rigueur, the way in which The Hidden Cameras blur the divide between performers and audience is glorious. It’s more intellectual movement than mere excess. Many talented Camera members practice art, academia and activism as much as music, which gives the group a truly unrivalled and exceptional pedigree.

In their reinvention of a new kind of pop life, every converted soul translates to a minor miracle. They get it; they get what pop should be. This is the subconscious soundtrack of national projects like Youth Assisting Youth and Free To Be You And Me. This is truly the music of kids sharing their toys.

* The Hidden Cameras’ new album Mississauga Goddam, will be in stores on Sat, Aug 7.

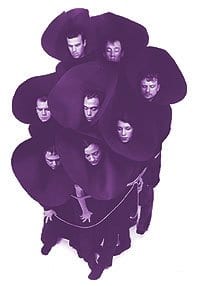

THE HIDDEN CAMERAS.

$10. Fri, Jul 23.

Trinity-St Paul’s United Church.

427 Bloor St W.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra