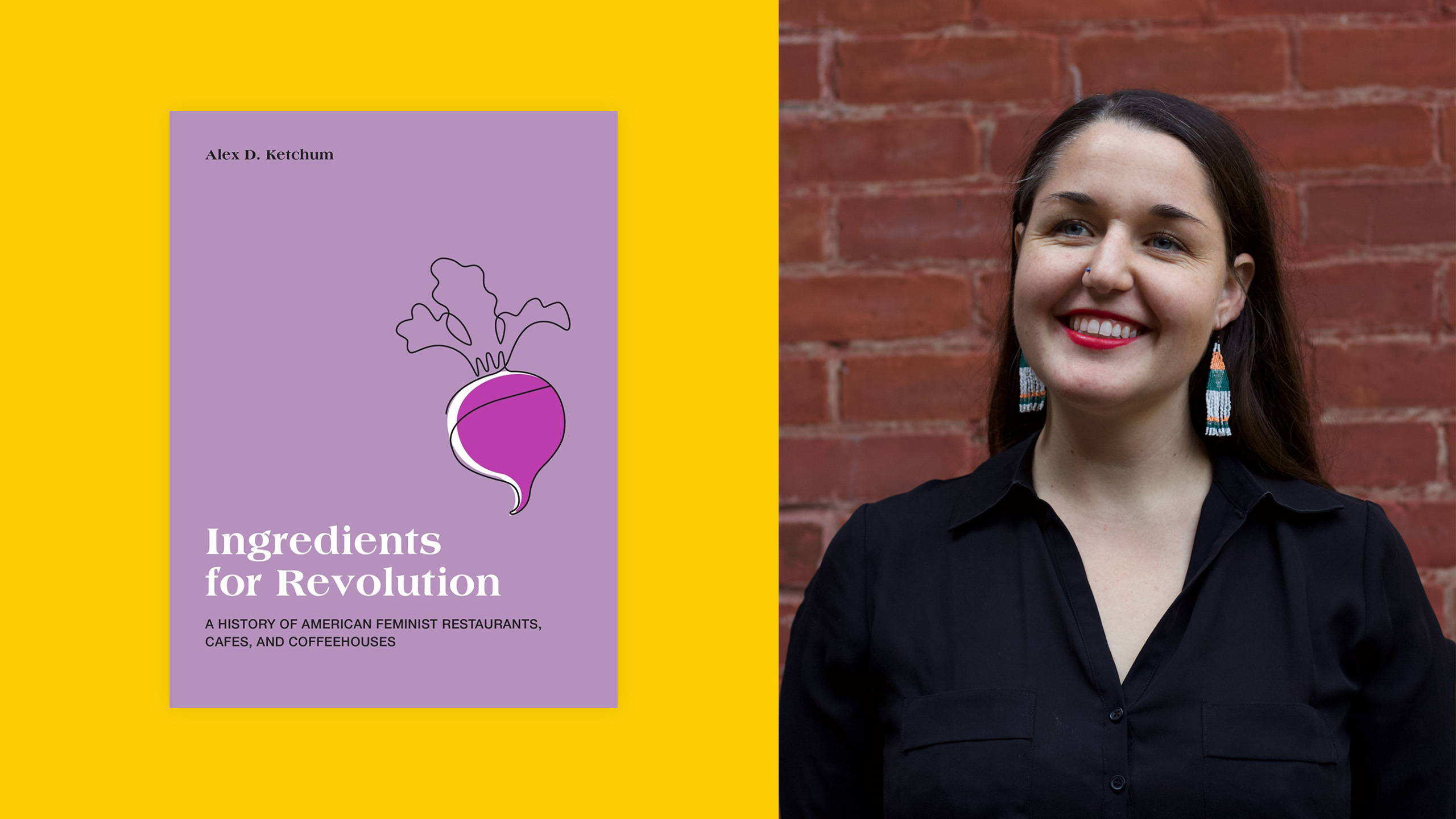

In her new book Ingredients for Revolution, writer Alex Ketchum explores the rich history of feminist restaurants, cafés and coffeehouses across Canada and the United States. Focusing on their heyday in the late 1970s and ’80s, when there were hundreds across the continent, she examines the motivations of the women who launched them and what they did for their communities.

“Feminist restaurants provided homes away from home,” Ketchum writes. “Though never utopic, for many women they were the first entrance to the world of feminism—a movement that offered a vision for a more equitable world. These restaurants, cafés and coffeehouses were places where they could meet other women to build lasting friendships, engage in activism, and find purpose in their lives. For others, these spaces were places to meet lovers and explore their lesbian identities in a new way or in a first way. Their legacy persists because these places were more than restaurants; they were centres of community.”

Though only a handful of the original enterprises exist—blaming the changing times, rising rents and squabbles among collective members—new ones have opened in this century, particularly after 2015. (Check out our picks below the main story.)

We talked to Ketchum about why these spaces were—and are still—important, and why we should be searching them out on our travels.

This book had me wanting to have a vegan meal served on a wooden table with mismatched chairs, while listening to Meg Christian play on a tinny speaker. What attracted you to this topic?

When I was an undergrad at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, I was co-running the school’s organic farm. I had founded a living community called Farm House, which was about food politics, and I was doing feminist studies and history courses and I was starting to work on my senior thesis. A friend recommended that I visit Bloodroot [in Bridgeport, Connecticut, founded in 1977], which was a 40-minute drive away. I was immediately intrigued by the space, the food, the community that they were able to build. I wrote a little bit about Bloodroot back in 2011 but continued looking at the history of feminist restaurants, especially ones that are run by lesbians and queer women. I’ve been out as bi and queer since the end of high school, but I didn’t fully realize until pretty late in the project that so much of my interest was about trying to find the kind of spaces that I wanted to go to and that I wanted to be a part of. Going through this history helped me figure some things out about the kinds of communities that I was seeking out.

If you spend any time in LGBTQ2S+ communities, the one thing you hear over and over is about the dearth of lesbian bars. But your book convinced me that maybe those energies went into cafés, restaurants and coffeehouses instead.

I think there’s a lot of really important work about the loss of lesbian bars and the important work lesbian bars do for community building. But especially for folks who didn’t want to drink, folks who were sober for different reasons, it’s nice to have alternatives to the bar space. A lot of the people in the book who started their own restaurant did talk about wanting to have spaces that weren’t just the bars. One of the advantages, too, is that they could be all ages; people could bring their kids, which was important—a lot of lesbians, for example, are mothers. This is part of the history that hasn’t been given as much attention and one big reason for that is because a lot of these businesses labelled themselves as feminist rather than lesbian, even if they were run by lesbians and women who today would fall under the queer umbrella.

You define the businesses you discuss as feminists because that’s how they defined themselves. Could you map out the relationships between the feminist label, the lesbian label, the lesbian feminist label for me?

There were some straight women who ran these spaces, but over time it became clear that the majority of them were lesbians or women who were in relationships with other women, but didn’t necessarily use the term lesbian. There were some in the 1970s that were run by women who considered themselves political lesbians—being lesbian as the embodiment of their feminist ideals, which is a different understanding than lesbian desire. But I wouldn’t necessarily use the term lesbian feminist because that’s become a brand of feminism connected to radical lesbian separatist feminism, which sometimes can get kind of TERF-y. There was some trans-exclusion in some of those spaces and some were trans-inclusive.

Were there any back in the 1970s and ’80s that were concertedly trans-inclusive?

Well, some were and some weren’t. I was able to find an example in Minnesota called A Woman’s Coffeehouse—it’s confusing because so many of them were named something like The Women’s Coffeehouse or A Woman’s Coffeehouse. I was able to listen to community events because someone put a tape recorder in the middle of the room and taped it. They had debates about whether or not it would be open to trans women. There was a sign that was posted that trans women could be asked to leave, but not everyone agreed with this policy, not everyone would endorse it. In other places, it was debated but they decided to be more inclusive. The places founded in the 2000s and beyond, they tend to be really, really trans-inclusive. Many of the staff in these places are trans and they make it very clear how trans-inclusive they are. You see these shifts in feminism and queer culture over time.

Many of these businesses were established as a political statement, a reaction to the restaurant industry being so male-dominated. How does that idealism flow through to the customer experience or the experience of the surrounding community?

In part, there was material support in that they created spaces where artists and musicians in the community, lesbians and other women, could have a place to showcase their music and their art. They hired women plumbers, women carpenters, women architects. They provided space for different community groups to meet and oftentimes they would also sell books and stuff, create other supports, create a space for information. They’d have bulletin boards so people could find out about community events, see job postings, housing postings and stuff like that. They also created social impacts because they provided a place for people to gather, to linger, to meet other people, to find friends and lovers and community. A lot of them were experiments by people who didn’t have a background in business management or restaurant work so oftentimes they would train other women in the community about lessons they had learned.

You write about whether these restaurateurs created an idea of “feminist food” or “queer food.”

I originally had a difficult time defining feminist food. Is it the business practices or is there something specific about the food? I looked at hundreds of restaurants and most of them tended to be vegetarian or at least have vegetarian options. As time has gone on, many of them have vegan options or are vegan only, and they often link this to environmental impact and ecofeminist principles. Many of them are really interested in the sourcing of their ingredients, trying to make sure that farmers are properly compensated. Many, but not all of them, are trying to use seasonal menus again because of environmental impact. It also impacts the cost of the ingredients. They often wanted to make sure that the labour of cooking the food was properly compensated, what we’d today call a living wage, although I would say that was the place where many of them failed the most because they’re also trying to keep prices accessible for customers. As an overall group, lesbians in the 1970s and ’80s tended to be overall poorer, so these places would have at least some really cheap menu items, so people could get a cup of tea or a cup of soup and stay in the space for hours. Some would have a sliding-scale menu. There was also this tendency to name dishes after famous women in history, feminist figures or lesbian figures.

In their heyday in the 1980s, were there things about the decor that would communicate to the desired customer? You’d look around and think, “Oh, I know what kind of place this is?”

I was looking at pictures because the vast majority of them have closed. But you’d see some consistencies. Because many of them were started with very little startup capital, there would be a lot of secondhand stuff, prints that might not match, mismatched furniture. Art on the walls supporting local women artists. There would be a lot of posters. The bulletin board would be a big indicator, with its changing political messages. Some of it was very ’70s: potted plants, tapestries. Whether there was a bookstore or not, there’d be books to read. There was also the sonic environment. A lot of attention was paid to the music, a lot of it then called women’s-movement music.

In the spaces still around today, especially the ones that opened after 2015, there’s more emphasis on queerness, there’s a wider variety of aesthetics.

You mentioned a kind of boom in 2015, 2016. Why do you think that happened?

Trump, the rise of Trumpism. It’s not that there weren’t queer restaurants and cafés opening throughout the 1990s and 2000s. But after Trump there was seen to be a need to market them as specifically feminist restaurants, making an explicit claim partly to counter the rise of Trumpism in the United States.

The new-generation of feminist restaurants and cafés tend to be more overtly queer-identified and their aesthetics are more up-to-date. What else has changed?

In the 1970s and ’80s, they pretty much were, with a few exceptions, run by women only. Even if men could come into the space, they were women-run. Now there are also a lot of spaces that are run by non-binary folks, gender-nonconforming folks, and some men are included in the collectives. They tend to have multiple streams of revenue, which helps them be more stable. A lot of them are bookstores-slash-cafés or bookstores-slash-restaurants,

Which of the remaining places have you visited?

Credit: Alex Ketchum

Bloodroot was my first. I’ve been outside of Big Kitchen Café in San Diego, but embarrassingly, I didn’t go in because I felt too shy. I was quite young. The Common Womon Club Restaurant in Northampton, Massachusetts, hasn’t been open for a decade, but it’s a Middle Eastern restaurant now and I went and ate there just so I could sit in the space. There are places that exist today that are kind of difficult to categorize, like Dear Annie in Cambridge, Massachusetts, because they call themselves a feminist wine bar. In New York, I’ve been to Bluestockings and Lagusta’s Luscious in New Paltz. Lagusta’s businesses are amazing.

Describe what it’s like going into Lagusta’s Luscious.

She recently changed the colour aesthetic, which used to be blue and pink—now it’s green and gold. When you enter the space, there is a beautiful chocolate counter because she’s a feminist vegan anarchist chocolatier. There is explicitly queer and feminist art on the walls. There’s a wall of mitzvahs, from Jewish culture, which represent a good deed that you’re doing that day. It’s basically paying it forward, like: here’s $5 towards the order of someone who is having a bad day or here’s something for a cup of coffee for a black trans woman who just needs a smile, here’s something for a new mom. There’s this feeling of encouragement. Then there are bookshelves with feminist books, queer books, books about food. There’s a zine library. The food is vegan. There is socialist soup, which is basically pay-what-you-can soup. Then Lagusta herself, if she’s in the space, she’s usually wearing brightly coloured clothing and she has a dog that sometimes wears an outfit. It’s staffed primarily by queer people from the New Paltz area.

Sounds great.

It is.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The feminist eatery tradition carries on

In California

The Cheese Board Collective Bakery and Pizzeria (1504 and 1512 Shattuck Ave., Berkeley, California). A worker-owned co-op since 1971, they don’t use “feminist” in their current description, but remain a delightful place for well-made baked goods and, of course, cheese.

Newcomer A Seat at the Table Books (9257 Laguna Springs Dr., Suite 130, Elk Grove, California) was founded in 2021. Avocado toast and smoothies? Check and check.

Big Kitchen Café (3003 Grape St., San Diego, California) has a few rules including: do unto others as you would have them do unto you, do not deliver your baby in my café, don’t keep score and do use the phrase “très bien” often.

In Connecticut

Bloodroot Feminist Vegetarian Restaurant (85 Ferris St., Bridgeport, Connecticut) was founded in 1977, making it the oldest surviving member of its species. The menu is likely more varied than it was four decades ago: think Thai curry, Jamaican jerk tofu chicken and asparagus with Vietnamese scallion sauce.

View this post on InstagramAdvertisement

In New York

Café con Libros (724 Prospect Pl., Brooklyn, New York City, New York) declares itself to be an Afro-Latinx- womxn-owned intersectional feminist community bookstore and coffee shop which hosts regular events.

Bluestockings Bookstore, Cafe and Activist Center (116 Suffolk St., New York City, New York) is a collectively-run activist centre, community space and feminist bookstore that has been operating in the Lower East Side for more than 20 years. More about books, events and politics than food.

Advertisement

Lagusta’s Luscious Café and Lagusta’s Commissary (25 N. Front St. and 11 Church St., New Paltz, New York) was founded in 2003 around artisanal chocolate and “a deep commitment to social justice, environmentalism and veganism.”

In Ohio

Iris BookCafé and Gallery (1331 Main St., Cincinnati, Ohio) holds book events and exhibits work by local artists. The food is locally sourced.

In Washington

Wildrose (1021 E. Pike St., Seattle, Washington), operated by lesbians since 1984, might best define itself as a bar—but it has food and lots of posters for community events so it’s got its heart in the right place.

This story first appeared on our sister site Pink Ticket Travel.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra