The first movie poster that ever intrigued me had a girl’s eyes floating over curtains billowing outward from a window. I tried to piece together what the film was about but finally asked my mother. An exorcist, she said, is someone who extorts money from you. Memo to Warner Bros marketing department: If you can’t make your message clear at least make it pronounceable.

If you’ve seen a lot of movies (or worked in the publicity end of the business like I have) you begin to really appreciate the slow, erotic anticipation of the movie-going experience over the actual sitting-through of the film. If the best thing on television these days is the commercials, the best thing in movie theatres is the promotional posters. Marrying marketing and art, they bottle that built-up optimism into 27×41 inches of glossy paper stock.

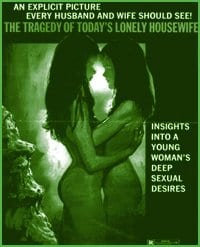

Jenni Olson’s The Queer Movie Poster Book captures a lot of that excitement. Oscillating between images and taglines that are alluring (“What he inherited was a sexual awakening…”) or lurid (“A scorching drama of the most un-talked about subject of our time!”), its posters are often poignant memory-lane statements about the social mores of the time and the on-going struggle for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender equality.

That battle continues today because many of the movies about queers, for queers or afraid of queers are still produced by straights. Sexual orientation is disorienting for most of these filmmakers and it shows in their movies and on their posters-and always has.

“Uber-butch Wallace Beery,” the book reports, “first made a name for himself” in Sweedie’s Hero (1915), one of a “wildly successful series” of drag follies starring a fey man-child character. (Another title in the series was Sweedie’s Suicide.)

Around the same time, however, silent film star Alla Nazimova’s tribute to Oscar Wilde, Salome (1923), was said to have had an all-gay cast and sets and costumes designed by Nazimova’s lesbian lover (who was also the wife of Rudolph Valentino).

But overall, the genealogy of queer cinema is surprisingly simple-mostly because US censorship restrictions made it impossible to release an overtly pro-queer film until the 1960s. Only a few dozen films made before then had overtly queer themes, though their posters rarely admitted it. More often they contained subtexts that generations of lesbians and gay men have claimed for themselves.

While straight mainstream movie posters target their market outright, depicting their characters and story lines, queer movie posters still deal with mixed messages of don’t ask, don’t tell, just sell.

Most early queer movie posters featured lush, florid full-body Harlequin illustrations of pretty women and too-handsome men giving each other that indefinable queer eye. Ironically, when photographs became the norm, the images were from the neck up, literally bringing you the (tormented) head of a queer: Al Pacino’s clenched face from Cruising; the merging heads from The Consequence; Mariel Hemingway about to give her wet-lipped Personal Best.

Subtext finally became text-literally-with the classic handholding, print-heavy, photo-came-with-the-frame poster from Making Love (1982). If you didn’t know how to be queer, this film would teach you: it’s as easy as acting straight.

The book also includes posters for films marketed towards bisexuals (Score, Sunday Bloody Sunday), queers of colour (My Beautiful Laundrette, Tongues Untied) and the transgendered (Tootsie and Victor/Victoria, the book says, ushered “in the genre of bad mainstream drag movies for straight audiences” like Mrs Doubtfire). And its gallery of “dykesploitation” posters features lots of torrid girl-on-girl action-and a million exclamation points!

Meanwhile, its posters of Guys With Their Shirts Off show exactly that and the chapter on the “one-handed amusements” of Early Gay Porn posters could easily parallel the evolution of the photocopier and fanzine.

It may sound like camp-and much of it is-but queer readers are going to see a lot of themselves in this book.

These are the movies we heard our parents make fun of when we were children, these are the films that cued our first exhilarating little shocks of queer recognition, these movies are the miscellany of cultural signifiers that ultimately helped us carve out a queer identity.

The book ends with a poster for 101 Rent Boys and a prediction of more “gay movies with campaigns that are genuinely mature and not sophomoric.” It also forecasts “more skin and sex in indie gay film marketing than ever before, whether the films themselves are sexy or not.”

And lesbians, the author warns, “will continue to get a steady stream of so-so features with really cute girls on the posters, and the occasional brilliant masterpiece that makes us hold out hope for the future.”

THE QUEER MOVIE POSTER BOOK.

Jenni Olson.

Chronicle Books.

132 pages $27.95.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra