Black Hollywood keeps failing me.

Maybe it’s because I, a Black, queer, non-binary person of trans experience, have unrealistic expectations of what representation and inclusion should look like. Maybe it’s because I’m looking to cishet creators to shoulder undue responsibility in the stories they choose to tell that include, or at minimum reference, my communities. Maybe it’s because I just can’t take a “joke.”

But on the heels of the release of Coming 2 America—which includes a minor, tasteless and unnecessary reference to trans people—the continued use of our lives and bodies for comedic gain is tired and disappointing.

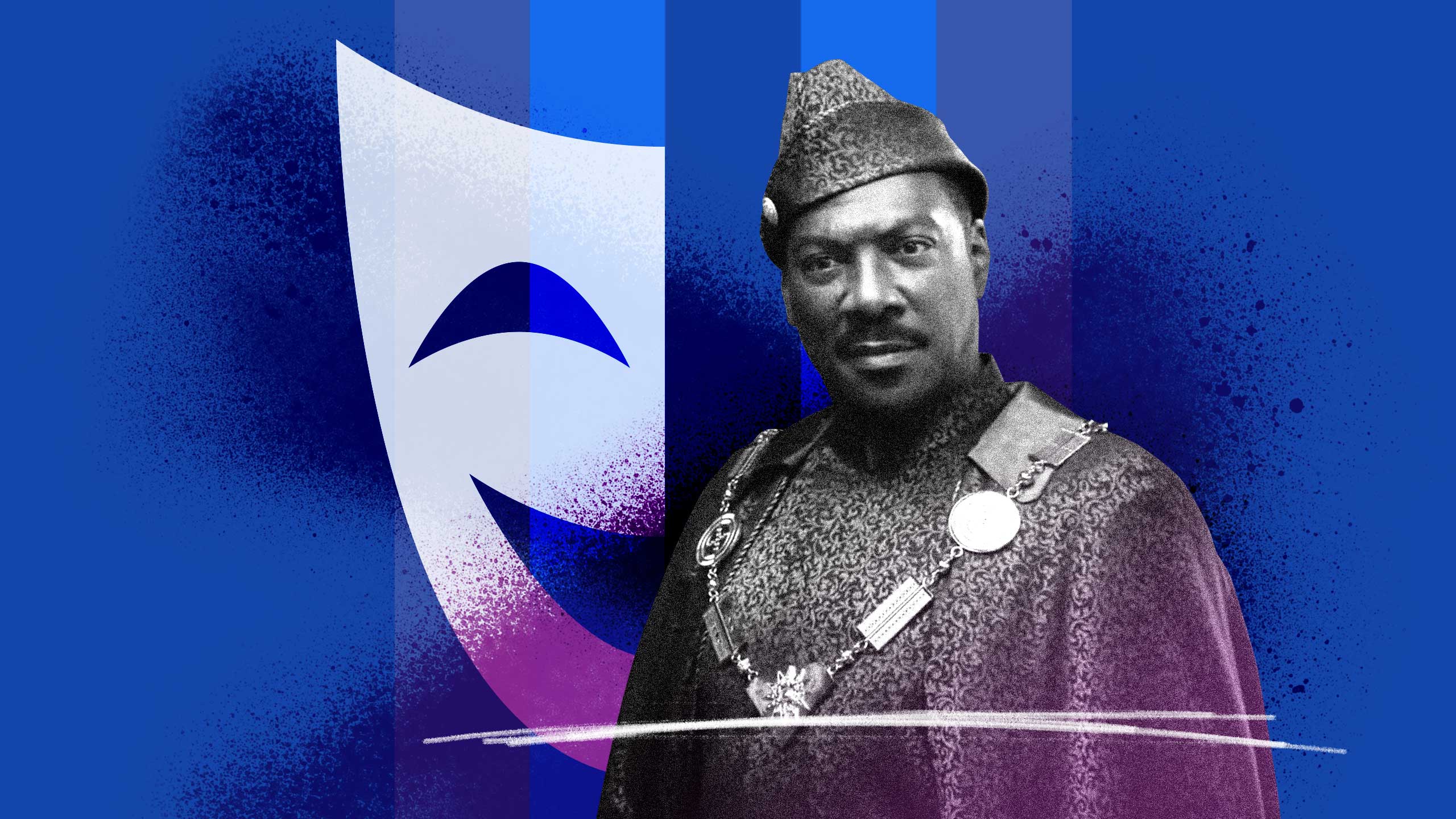

A sequel to the original 1988 film, Coming 2 America picks up decades later as Eddie Murphy’s Prince Akeem becomes king of the fictional African nation Zamunda. But because he only has daughters and no male heir to assume the throne upon his eventual death, the kingdom is in jeopardy of being overtaken by Wesley Snipes’s General Izzi. When Akeem finds out that he actually does have a son, conceived after a date-rapey one-night stand in Queens, New York, with Leslie Jones’s Mary Junson, Akeem sets out to find him and teach him (Jermaine Fowler) how to be an African leader. While I’ll let other critics and reviewers dictate the worthiness of the storyline and quality of the performances—spoiler alert: Eh!—I want to zero in on one scene in particular that, upon my first watch over a month ago, soured my viewing experience.

Relatively early on in the almost two-hour comedy directed by Hustle & Flow’s Craig Brewer (with writing credits going to Black-ish’s Kenya Barris, along with Justin Kanew, Barry W. Blaustein and David Sheffield), Akeem returns to Queens in search of his son. He makes a pit stop at a barbershop that his younger self (in the original film) frequented. The barbers and guests in that shop—most of whom are also played by Murphy and Arsenio Hall in prosthetics—make “jokes” when Murphy and Hall (as Akeem and Akeem’s best friend and aide, Semmi, respectively) walk in.

“Look who done come up in here,” one barber says.

“Kunta Kinte and ebola,” says another.

“Famine and blood diamond,” says the first guy.

“Nelson Mandela and Winnie,” says a third.

When the customer getting his haircut pipes in with “those hungry babies with the flies on their face,” the barbers are enraged. They kick him out of the shop citing the joke as “politically incorrect.”

After some humourless commentary on gentrification and the resurgence of Nazis, the main barber asks Akeem if he has kids. In doing so, the barber says, “I got one granddaughter who used to be my grandson. They can turn your penis into a vagina now.” Both Akeem and Semmi silently react in disbelief, or perhaps amazement, to which the barber quips, “It’s science.”

I had to pause the film for at least 10 minutes to process my disappointment. As the “joke” replayed in my head, I tried to suss out its necessity. I’ve come up empty. But what I know for sure is that folks have a habit of casually including trans people in a narrative unnecessarily as a means of demonstrating how of-the-times a project may be—a way to signal to the audience that the film is especially self-aware of the broader socio-political world in which it was created. In response to such inclusion, I, more often than not, hear trans people asking, “Now why are we in it?” à la NeNe Leakes.

To be clear, the issue is not necessarily that the character said his granddaughter used to be his grandson. The issue is that the “joke” could’ve ended there; but by referencing genitals and surgery, the comment essentializes and medicalizes transness in a way that, historically and contemporarily, leads to the sensationalization of our identities. And even though it’s a small mention, we can’t divorce it from the broader context that establishes such references as anti-trans. I’m also tired of filmmakers thinking such cursory, offensive trans “inclusion” is a sufficient way to acknowledge trans people exist.

Undoubtedly, all of Hollywood is complicit in this same behaviour, and I’m concerned when any transphobia makes it to screen, no matter if the perpetrator is white, Black or otherwise. Yet, there’s a part of me that expects those who benefit most readily from whiteness and cis-ness to be trash and self-serving. Hell, in many ways, it’s their birthright. But when Black and brown people, in and out of Hollywood, replicate the very -isms and -obias directed at us and use them in reference to the members of our communities who are not cis and not straight, it hits differently.

“When Black and brown people, in and out of Hollywood, replicate the very -isms and -obias directed at us and use them in reference to the members of our communities who are not cis and not straight, it hits differently.”

In 2019’s Little, for example, Regina Hall’s Jordan has a problematic jab involving a child she misgenders. When corrected by the child’s parent, she retorts, “Oh, he’s transitioning?”—a line that was called out by various film critics and moviegoers as an issue. Even Tracy Oliver—who is listed as co-writer of the Marsai Martin-led picture but said she did not write those words—found it “insensitive,” “unnecessary” and “mean-spirited.”

Just last month, Saturday Night Live’s Michael Che came under fire after he made a dig at the expense of trans people. During the show’s “Weekend Update” segment, he broached the topic of President Joe Biden’s repeal of Donald Trump’s ban of trans folks in the military. The punchline: “It’s good news, except Biden is calling the policy, ‘Don’t ask, don’t tuck.’” (Other parts of that John Krasinski-hosted episode were also called out for homophobia.)

Still, I’m hesitant to boil down all of these behaviours to simply transphobia. While they are certainly anti-trans in nature, I think something else is at play.

Writer Julia Serano’s work details more precise language used to distinguish between certain anti-trans attitudes and positions. There’s “trans-unaware” to describe the uninformed or under-informed; folks who may be “passively transphobic” but potentially open to giving up such attitudes upon greater education. There’s “trans-antagonistic” for folks who are “opposed to transgender people for specific moral, political and/or theoretical reasons,” for whom education and outreach is unlikely to make an impact. Then there’s “trans-suspicious,” a position that “acknowledges that transgender people exist and should be tolerated (to some degree), but routinely questions (and sometimes actively works to undermine) transgender perspectives and politics.” These are the folks whose cisnormativity and cissexism are so strong that they end up embracing the very misinformation and anti-trans behaviours of their trans-antagonistic peers.

While I’d like to believe that the aforementioned productions are the result of trans-unaware folks, knowing the cycle of outrage and attempted accountability that’s activated after each infraction and bigotry-as-comedy takes place removes naiveté as a potential defense. At this point, it feels intentional, like somebody purposefully wants to contribute to the ongoing marginalization and oppression trans folks experience—especially considering how so many of these supposed “funny” references to trans people are just cis people talking about trans folks’ bodies. I know it can be jealousy-inducing to see the ways we create ourselves for ourselves, but the response shouldn’t be to make fun of us; it should be to figure out how you, too, can access your own autonomy.

I just want cis people to stay out of trans people’s business—it really is that simple. Don’t include us in your narratives if we’re only there to make you laugh or be the punching bag. Stop creating things that reference us without us being involved in the creation process. Keep our names and identities out yo’ mouth. After all, in the words of Viola Davis’ Aibileen from The Help, “Ain’t you tired?”

We surely are.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra