In the early days of my transitioning in 2020, I clung dearly to Charlie Jane Anders’s A City in the Middle of the Night. I initially read the book in 2019, appreciating its messages about climate change. The novel also profoundly dealt with the trans experience and the awkwardness of transitioning. As an awkward 20-something-year-old trans person, I felt seen. I related to the principal character, Sophie, a human who slowly starts to inhabit a non-humanoid body after coming into contact with the Gelet, a telepathic and highly intelligent native species of a planet called January. The process of change was depicted as beautiful, albeit clumsy, as Sophie got used to her new body. I no longer felt scared and uncomfortable about the initial months of HRT.

Anders, an American fiction writer, has won several awards over the course of her career, including a Hugo Award for her novelette Six Months, Three Days, a Nebula Award for her novel All the Birds in the Sky and a Lambda Literary award for her debut novel Choir Boy. Over the past 16 years, she’s earned a reputation for witty prose and weaving complex relationships into innovative science fiction stories.

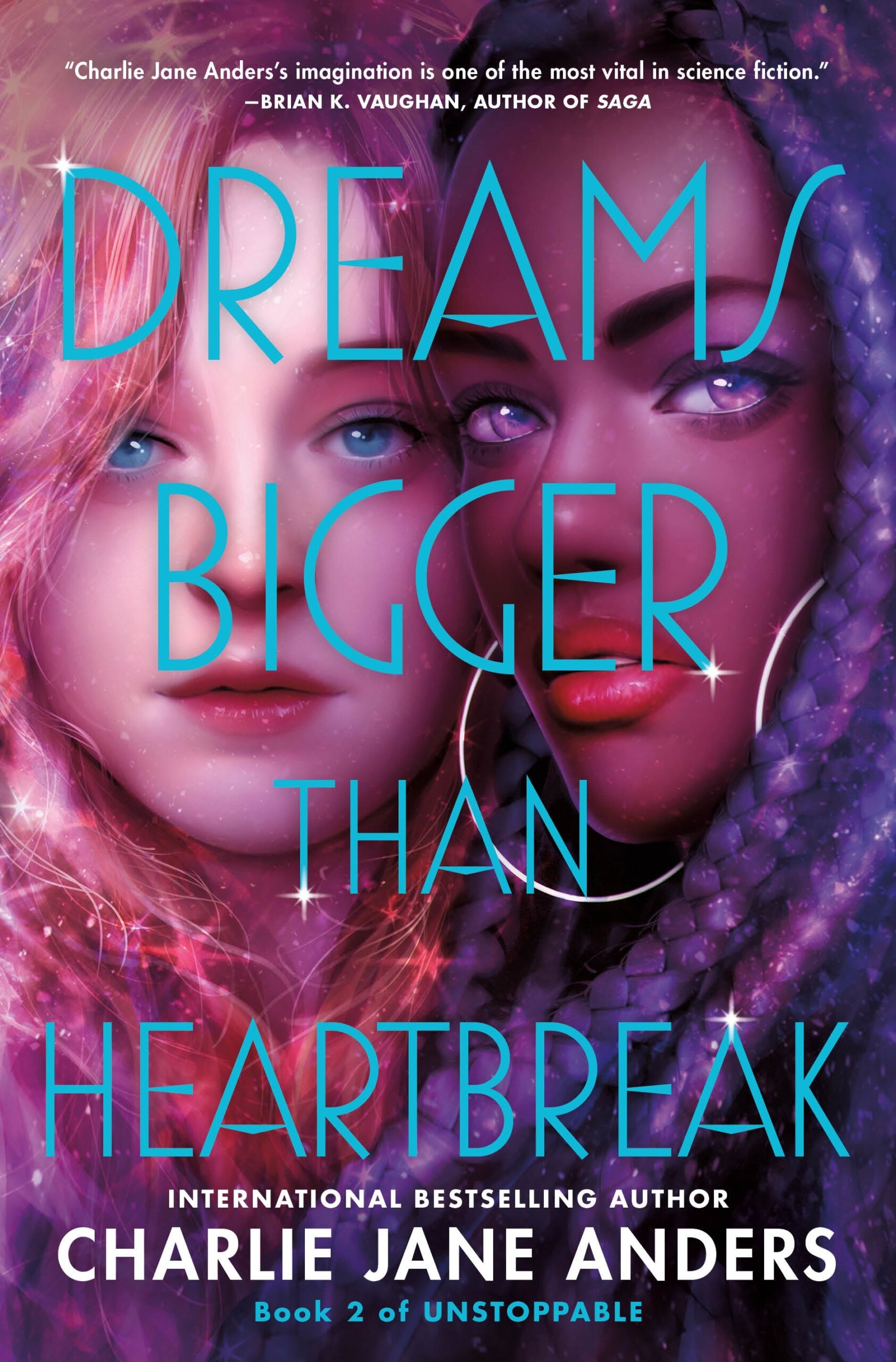

Credit: Courtesy TOR Teen

This spring, Anders published Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak, the sequel to Victories Greater Than Death in the thrilling Unstoppable young adult trilogy. The new book is a high-octane space opera that sees her protagonists, a fiery group of queer kids from Earth, struggle to make sense of their new roles within the Royal Fleet, a loose alliance of several different species plagued by court politics, in-fighting and the ongoing threat of the genocidal fringe group known as The Compassion. They are thrust into a high-stakes fight against a growing authoritarian galactic force and must carry out tense spy missions and make impossible choices between their sense of duty and their sense of self. For some characters, fighting to save the galaxy might mean leaving their friends behind.

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak also nods to the looming climate crisis by situating the story against the backdrop of an existential threat from an ancient alien race’s abandoned technology called the Shapers. The Shapers threaten to destroy the known universe, presenting readers with ideas about the legacy of a previous generation in manufacturing the climate crisis, only for it to impact future generations. Themes around trans identity are again present. One of the primary protagonists, Elza, is a trans girl from Brazil. This may be a YA novel, but Anders does not shy away from grappling with the intersections between class and gender identity through her nuanced depiction of Elza’s character.

During a stop on her book tour, I had a chance to talk to Anders over the telephone from a small café in Chicago about Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak, about why hopeful trans stories are so important and writing about finding one’s identity.

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak is set in a universe where the protagonists are fighting against authoritarian forces. What was the motivation behind making the main villain of the story xenophobic fascists?

That’s a massive concern for all of us right now. Authoritarianism is on the rise, and it’s a terrifying thing. So in my first book in this series, Victories Greater Than Death, I tried to gently seed the idea that the Royal Fleet isn’t perfect. They’re not as great as they think they are. The Compassion are a splinter group from the Royal Fleet that has taken their ideas in a much different direction.

This is something that I love about big space stories like Star Trek and Star Wars. You get to tell these big political stories about empires and the fight for control and domination within those empires. That is a thread that runs through a lot of science fiction, and especially with space operas. It’s about who controls resources and who gets to control the fate of worlds. On the other hand, these big space opera stories tend to be about America in one way or another. When you watch Star Trek, it is undeniable that the Federation is meant to represent America. Starfleet is the U.S. military, and they’re coming to fix everything with their superior values. Star Trek has moments when it waves its hand at being internationalist and tries to be inclusive of other nations. Still, the original structure of the show is very much about America. It speaks a lot to ideas about the American experiment and the notion of manifest destiny created around the formation of America. When you write a story like that, you write about America and America’s place in the world.

It’s incredibly interesting to see this developing trend in science fiction—novels that position the internal politics of the United States as the villains, rather than the long history of the villains being a vague allusion to Soviet Russia or some variant of the latest “threat” to the American way of life.

These stories often get America’s worst impulses. Many of them are about the worst and best versions of America in conflict with each other. I write a lot about identity and trying to find your own identity alongside ideas about violence, and whether violence is ever justified or whether it’s the best option. I write about these ideas because I feel like there are things embedded in many of these heroic stories that we don’t always think about that are shaped by a very particular set of values. Something that has made me happy in recent years is seeing some heroic stories about building community. So many people talk about choosing family as a heroic act, but I think finding a community and building a community that can raise everyone is heroic. The same goes for being your true self. So I feel like I’m trying to question our heroic narratives, and hopefully in a fun and not a sermonizing way, while also giving people other ways of thinking about heroic stories.

Rest assured that it is an entertaining read. You spoke about identity earlier and have written about identity in your creative writing memoir Never Say You Can’t Survive. You spoke about how you cannot divorce politics from identity. Was Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak a way to build out that idea further? The book has a lot of moments where it hints at the idea that simply existing and fighting for your survival is a form of politics and activism.

I think that that’s true. It comes down to who gets to have a voice and who gets to be represented. A throughline through the book, and a lot of my other work, is the question of who gets to be a person, who gets to be kind of considered a person and who gets to be considered a non-person. It’s not even an examination of humanity, because you can be considered a person without being human, but rather, who gets to have all those constituent parts that embody personhood. It’s the idea of who gets to be a person that counts within the world, and who gets to have a say in what happens to them.

Given everything going on in the world right now regarding anti-trans legislation being passed all over the United States and the anti-trans rhetoric that is coming out of the United Kingdom, what were your hopes with writing something that allows queer kids to find joy, happiness and solidarity, even while existing in an oppressive system?

Everybody is getting bombarded with so many negative messages. And even the supportive messages are very often very reactive about the negative stuff. In reality, they’re not monsters. They’re not scary. They’re not the force of evil. They’re just kids. I want to show that they can thrive and be joyful and have amazing relationships with people who see them for who they are, like showing that you can thrive and that you can be joyful, and that you can, like, you know, have amazing relationships. All of that is something that many people need to read right now, especially younger trans people. I did an event in Seattle, and two young trans kids came and wanted to ask me how to deal with everything that is going on right now. It was heartbreaking and intense, and I tried to be as comforting as possible. Thinking about that, stories like this are so important right now.

The books are at the forefront of queer science fiction that discusses the intersection of queer joy and trauma. It is really important to have a book that acknowledges that the world can be awful, but you’re allowed to be happy and to find a space to exist as a person.

Exactly! We can’t just be fighting all the time and be in a defensive crouch. If we do that, we won’t survive. We have to have joy, and we have to have fun. There have to be fun and good times and laughter, or else what is the point of fighting for liberation? I have been super influenced by stuff like Steven Universe, She-Ra and Legends of Tomorrow, which foreground joy in the face of world-ending circumstances.

Race and species have been incredibly unimportant in both books in the Unstoppable series—except to the ugly racists. This is a refreshing approach to writing science fiction, especially given how many books within the genre fixate on interspecies conflict.

I’ve thought a lot about the hierarchy of humanoids and non-humanoids and the whole narrative of humanoids versus non-humanoids that people keep trying to impose in these books. It’s a big thing in space opera. When you watch Star Trek or Star Wars, everybody is a human. This was probably for budgetary reasons at the time, but besides some prosthetics or some fake fur, they are humanoids. Whenever they meet an alien species that is a blob or something like that… it’s scary and weird, and not something humans can deal with. Of course, many of these episodes follow a narrative of learning to recognize that this is a living creature with its own point of view and a right to survive. These episodes were pretty provocative at the time. But the bottom line was that [these non-humanoid creatures] had the right to be treated like anybody else. If everybody is humanoid, then how are we going to interrogate that?

A thing that stood out to me in Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak is the strong emphasis you place on positive friendships amidst a high-octane space adventure. What was your intention behind doing that? And what do you want people to take away from the way you’ve written those scenes?

I kept thinking about that. It is very easy to just write, either getting to the next plot device or dealing with the logistical stuff of getting to the spaceship and doing the thing or blowing up whatever the characters need to blow up. It is easy to have the characters always be in conflict because conflict is inherently interesting. We’re living in an upsetting time, so I kept coming back to wanting to write a story where the characters check in on one another. It is the kind of story I enjoy as a reader. I wanted to write about people who pay attention and are there for each other in a fundamental way. I wanted characters to check in, take care of each other and be mindful of each other. I feel like people throw around all the tropes about chosen family, but for me, that’s what it is: you prioritize one another’s well-being. It comes back to respecting everybody’s identity and personhood because you have to be mindful of other people, or it’s all just words. It ties back to building a community and maintaining a community.

And building alliances across partisan lines, which is sort of something we need in the real world.

Right. And building alliances. I’m interested in writing about building alliances. That is the kind of thing that grows over time. You end up working with the idea of what kind of alliances are we going to build and how are we going to include people who have been left out before.

That is something I tried to do to the best of my ability. In the second book, we want to make peace, and we want to avoid a war. But are we gonna make peace with the fascists? And what does that look like? How far are we willing to go to make peace? One of my favourite things in Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak is when Elza arrives at the place for the first time, she is on her own. She immediately looks for the other outcasts so that she can bring them all together, which is the thing you should do in that situation. I wanted to model that kind of behaviour.

Before becoming a fiction writer, you were a journalist. What caused you to leave the field of journalism for fiction?

I’ve always had a weird imagination. When I was doing journalism, I would always try to find the weirdest stuff to write about and then get sad because it wasn’t weird enough, or because I couldn’t include the weirdest parts or because, you know, in journalism, things did have to make sense, which is a huge restriction. I always wanted to write fiction, and journalism was just a thing that I did. It was a way to get paid for writing while trying to break in as a fiction writer. It took me a long time to break in as a fiction writer. However, journalism let me learn a lot of really different stuff. It exposed me to a bunch of tool sets for doing research. I just learned a lot about how the world works by doing journalism. It was just more fun to make up stories. I know many people who’ve become refugees from journalism in fiction-writing or creative pursuits. At a certain point, it’s kind of just liberating to get to make up stories. I feel that you can’t tell the truth about the world with nonfiction in the same way you can with fiction. Fiction allows you to streamline things and get to a deeper truth.

We have seen this massive explosion of trans authors publishing science fiction stories in the past few years. What are your thoughts on how trans authors are given more space in the genre?

It’s been amazing to watch new waves of trans, non-binary, gender-fluid and genderqueer authors coming into genre fiction. There’s just so much weird, imaginative, bizarre stuff being published now. There are a lot of retellings of mythology that break the genre in interesting ways like Wrath Goddess Sing by Maya Deane. And then other stories break the genre even further. For instance, some amazing body horror is being written, like Hell Followed with Us by Andrew Joseph-White. There are just so many books that are off-kilter and tell stories in so many different ways. You can tell that people have a lot of pent-up energy and that authors are just excited to finally get out and write the stories they’ve wanted to write for a long time. We’ve experienced a lot of stuff differently than other people in some ways. For instance, we’ve had a different relationship with our bodies, technology and the medical profession. There are just many ways in which we have had to have a different relationship with the world. I think it leads to stories that are slightly different and speak about queer liberation and resistance. There are a lot of marginalized groups that are just getting to take these stories that have always been there and find a new spin on them, but also just find entirely new stories to write. And it’s just it’s so great to see.

Speaking of emerging trans authors, I have had the pleasure of talking to a few recently. Your name comes up a lot. How does it feel to be so prolific?

I don’t feel like I’m prolific. I feel like I write incredibly slowly—my publisher always tells me to write faster. But at the same time, it is so great to get to be part of a community. When I started out trying to write speculative fiction, people, including some trans people, told me, “You know, if you’re openly trans, you will never be successful in science fiction and fantasy. It’s just not a thing.” Sure, we did not have many openly trans authors when I was starting. We had Rachel Pollack and that was about it. There were authors who we thought could have been trans, but we did not know for sure. Due to the handful of authors, I was told that my identity would keep me out of mainstream science fiction and fantasy. That has changed, and it’s been so great to watch.

There’s also the fun game of figuring out which authors in the 1960s or ’70s were trans, but you can never say for sure.

You can’t. You can’t impose identities on people who aren’t even here anymore, but there were authors around who were openly trans. It is not surprising that we can’t identify many openly trans authors from that time. There were not many, and the few that existed were pushed to the margins most of the time. The reality is that there’s always been more of us than people realize in speculative fiction. Jean Marie Stein, who published books like Season of the Witch in the ’60s, only transitioned 20 or 30 years ago. She was an author in the ’60s, but everything is under her deadname. Some of her science fiction short stories have been compiled in Herstory and Other Science Fictions.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra