For the past eight years, I’ve watched the Super Bowl with my friend H–. We alternate between her house and mine, and have included the various partners we’ve had over these years.

H– and I have shared so much of our adult life together. We’ve shared more meals than I can count, some cooked by her, some cooked by me, many cooked by strangers (ramen, noodles, pizza, Thai, dosas).

H– is vegetarian, and I take the task of making yummy veggie foods for her very seriously. She’d never had gravy, so for one Thanksgiving I made her one, veggies with a mushroom base.

“Oh,” she said later, “I get it now,” as she heaped another spoonful on her potatoes. I love people’s dietary restrictions, which make the meal a challenge. Every year for the Super Bowl, even though H– can’t eat them, I can’t help but make my absolute favourite Super Bowl snack: the mighty, the perfect, the Buffalo Wing, even if I’m the only one, between H– and me, who can actually eat them.

It’s a Sunday night in Brooklyn, it’s January and it’s raining. Super Bowl 2023, which we officially call “The Rihanna Concert,” is only a few weeks away. Devon and I moved recently, about a 15-minute walk from the neighbourhood’s one decent grocery store, but we do have a Discount Foods around the corner. Closed. The other Discount Foods four blocks up? Closed. The only remaining options are: 1) order food, but it’s Sunday and I am committed to cooking on Sundays; 2) walk my ass 15 minutes to the Pioneer Grocery by the Parkside Q in the rain; 3) see what’s on option at the fancy corner store with a small grocery section. I pick the corner store. The only protein they have: chicken wings. But they’re on sale, half off. I buy two packages, around 25 wings.

Amuse Bouche: Single Chicken Wing Drumette Lollipop (on a spoon, in-house-made pickled Fresno pepper

“Chicken wings, babe,” I say to Devon, as I walk in from the store. “It’s all they had.”

“Guess I won’t be bottoming tonight,” he tosses back. I know my own routine could withstand the greasy dinner, but it was a Sunday, after all, and who has the energy for that?

An hour later, between the wings’ first and second fry, I find myself whisking cold butter into a saucepan of warm Frank’s RedHot sauce under medium-low heat, until just over 50 percent of the liquid is butter and the sauce holds together in one perfect layer. As I explain to my biochemistry students a week or two later, it takes energy to hold water and fat in perfect emulsion, together in tiny particles and not separating back into pure layers of uncharged fats and partially charged water. One form of energy is heat, the stovetop, and another is movement, my whisk, and I whisk until I feel it in my triceps, a soft burn, and then I keep whisking.

“Bitch, you know what this is!” my muscles tell my brain. “Honey, you have been here before!” they scream.

“Buffalo sauce,” my brain says, catching up with the movements of my body, “is a beurre monté.”

Appetizer: Hands! (a collection of small bites from around the world)

Haute cuisine, the French term that roughly translates as “fine dining,” is a culturally French import, not just in the techniques—like making a perfect beurre monté that hasn’t split—but in terms of the organization of labour in high-end kitchens: The French Brigade. French chef Georges-Auguste Escoffier refined this system in a kitchen (ironically) in London based on military hierarchies and a commitment to cleanliness, order and perfection. Escoffier also defined the five French “mother sauces”—béchamel, espagnole, tomate, velouté and mayonnaise—although I prefer the non-gendered French grandes sauces, which I would translate as essential, important or maybe foundational sauces.

You can thank Escoffier for your fucking eggs bennie, you brunch-loving idiots.

“Susan Sontag, in her classic 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” defines that quality—camp —as a quality of “the degree of artifice, of stylization.” High-end kitchens are, by this definition, absolutely camp”

A beurre monté, or a mounted butter, usually involves a small volume of water heated to a soft simmer, into which cold butter is briskly whisked. This emulsifies the fat in the butter such that a thick liquid is formed, perfectly combined.

Susan Sontag, in her classic 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” defines that quality—camp —as a quality of “the degree of artifice, of stylization.” High-end kitchens are, by this definition, absolutely camp, from the stylized uniforms (those hats!) to the procedures of a boss (sous chef) shouting out comments or orders in a call-and-response with the ensemble returning a “Yes, Chef!” or “Heard!” or (best of all), “Oui, Chef,” borrowing the French entirely.

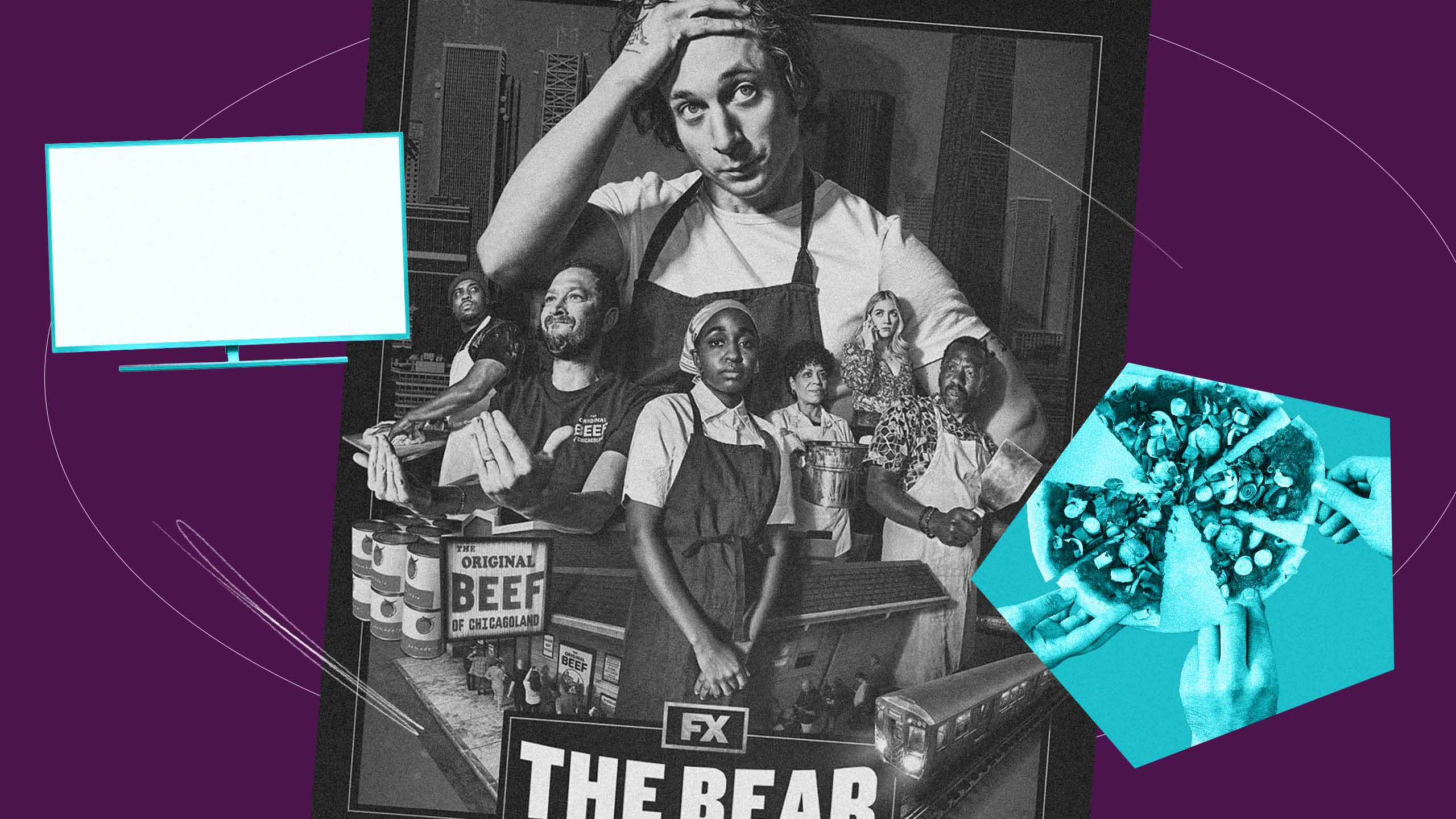

The FX show The Bear renders this ironically gritty, a kitchen brigade instituted in a struggling dive. It is a good show. The disconnect between the expectations of a high-end kitchen and the reality of their Chicago Beef hole-in-the-wall drives the interpersonal chaos we’re thrown into to the next, tension-filled level.

The 2022 movie The Menu is pure camp (but self-aware camp, more on this later), with the orchestration of the kitchen extended perhaps beyond even the obscene reality. The Menu brings us into a satire of the world’s best restaurants, with guests arriving on a boat, staff members lodging at the site and artifice inhibiting the soul of the cooking, even as the food is mindlessly gobbled up as perfect for its gimmicks (house-made tortillas, for example, with images printed on them of scenes from that evening itself). It is not a good movie. Its stylized satire and mockery of the film’s big stars and slick production somehow embodies the very consumption and precision (and lack of soul) that the movie is purporting to critique.

Haute cuisine kitchens, for their degree of artifice and stylization, are absolutely camp, and pure camp as defined by Sontag because they are absolutely not aware of it; for chefs, the kitchen is a serious place of battle. And yet, Sontag’s pure camp is stylization over substance (“to emphasize style is to slight content”) and the haute cuisine kitchen is camp to render content, the stylization and performance, the hierarchies and “Heard, Chef!” and “Behind!” are to serve, ideally, the food produced. Camp is “style over substance,” a common enough critique on The Great British Baking Show (very camp, very good).

Embracing the camp better than The Menu is the various iterations of the show Iron Chef, where an actor playing an eccentric rich person has accomplished chefs “Do Battle!” with a themed ingredient, utilizing extremes of scoring and production (so much fake fog). But the chefs here, unlike The Menu, generally make food that you’d love to eat, and I’ve been introduced to so many great techniques that I now use routinely (want to make tender short ribs in under an hour? Get them in the pressure cooker as soon as you can!).

The Bear works because of its ironic approach. Artifice out of place can make great art. We get one long flashback of Carmy, the head chef at the show’s centre, played by Jeremy Allen White, and his time in a high-end kitchen; while The Bear generally has that blue under-tint of edgy TV, this scene almost glows with whiteness to the point of overexposure. Carmy is plating; a chef (a saucier, I imagine) brings him a sauce to check.

“Broken sauce, Chef, make a new one,” he says.

“Yes, Chef,” she replies, with pain on her face.

She makes a new sauce.

“Still not there again, Chef.”

“Yes, Chef.”

“Thank you, Chef.”

The scene devolves into a nightmare, with the chef de cuisine humiliating Carmy over that very broken sauce.

A broken sauce is a mounted butter that has de-emulsified, its water and fat components splitting back into their natural order.

“Say ‘hands’!” the chef shouts at Carmy, and he does.

“Hands!” and a server comes to pick up that plate, bright red raw salmon on a perfectly white plate. “Hands!” an off-white ice cream with drops of a pink sauce in a perfectly white bowl. “Hands!” an orange dish, what looks like small rounds of sliced tomato, raw fish again perhaps, over alternating orange and white sauces on a perfectly white small plate.

And suddenly we’re back in Chicago, in the beef shop, soiled old call tickets littering the work space, with Carmy rolling up a greasy beef sandwich, slamming it onto a plate– not all white, calling for “Hands!,” or servers, to take the plate away.

The Bear shows the high-end camp kitchen Carmy quit to come home to Chicago as the stuff of nightmares. That a place so camp is also so often full of toxic masculinity reminds us that gender performance—masculinity, for example—is a cultural artifact; in the professional kitchen, masculinity is enacted in ways that could not be more different from the tiny logging town where I grew up. Perfectly white, perfectly starched, wrinkle-free clothing is the mark of the man in charge; back home, dirty blue jeans from a day in the forest cutting down trees was the supreme marker of masculine labour. And yet, the common denominator of toxicity—threats, impatience, demeaning language, bullying—remains so constant, from a logging site to a Michelin-starred restaurant.

“I make my own masculinity in a kitchen, in service of nothing but my joy and the pleasure of making and eating food, perfecting the foods I grew up with with the techniques I’m learning from the camp TV kitchens I can’t stop watching.”

Great kitchens are camp, then, in service of the process of making great food. And my love of cooking shows, from The Bear to Iron Chef to various viral YouTube channels, comes from the double joy of learning how to cook better myself while I am also entertained, challenged and emotionally engaged.

Where I grew up, haute cuisine does not exist. We are Hamburger Helper (which I love), not Jacques Pépin’s French-style burger et frites (which I learned later in life I also love). I make my own masculinity in a kitchen, in service of nothing but my joy and the pleasure of making and eating food, perfecting the foods I grew up with with the techniques I’m learning from the camp TV kitchens I can’t stop watching.

Primi: Anywhere, Anytime, Dive Bar

When I think of Buffalo wings, those perfect spicy bites, I think of two bars: The Rueb ‘N’ (Northfield, MN) and Bakersfield Bar (Upper East Side, NY). In college, the Rube had a special: buy beer at happy hour and all the wings you could eat were free. “All the wings we could eat” were never that many wings, because we would spot a fresh chef’s tray of wings coming from the kitchen, and, like vultures to the kill, a few dozen hungry college kids would rush to get in line. We all got a few wings, a dinner’s worth if we were lucky. In grad school, Bakersfield Bar had a Monday night special: 25-cent wings. Ten wings for a couple bucks. Here, we got what we ordered, as many wings as we wanted. Here, though, beers were around $8 a pop, not like that little Minnesotan college town, so we had to be careful.

Both bars had floors that were vaguely sticky. Both bars had lights that stayed low, a few tinted red to light up the walls for a mood. Both bars brought in patrons with the promise of low- or no-cost proteins designed to be spicy and salty enough that they would buy plenty of booze to make a profit.

Buffalo chicken wings are sauce-all-over-your face, napkins and a little wet wipe after. Buffalo chicken wings are made with a beurre monté, that workhorse of the kitchen brigade.

In a dive bar, you could be anywhere. A group of PhD students, all 20-somethings, mostly from families with some money and access, on NYC’s Upper East Side. Or college students, feeling special for one meal outside the dining hall. New York City, even on the Upper East Side, in a dive bar, could be Washington state. Walk through those doors and smell the light beer and faint touch of bleach, sit near the bathroom and the bleach gets stronger with an undercurrent of urine; these bars defy geography. That smell, now, transports me through time, confronts me with the child I was at 21 and the child I was at 25, who I do try to keep on nodding terms with, as much as I wince at his naiveté and the choices he was making then and would make in the years to come.

I’m 40, I don’t go out much anymore. At home, I can eat as many wings as I can cook, without worrying about the 25 cents adding up to an amount I didn’t then have in my bank account. Making wings at home invites all these memories inside, all those old friends and the people we were together at 20 or 25 years old. The chicken wing, a Proustian madeleine I can make myself whenever I want to remember.

Secondi: Pizza Margherita

The Bear is playing a game with expectations of high and low cuisine. Later in the season, when Carmy is showing his co-workers how to make a fancy version of the Italian American classic, chicken piccata, he even stops himself as he begins to say “You mount the butter.”

He stops, corrects himself: “You whisk in cold butter.”

For the last few years, since the COVID-19 lockdown, I’ve been incorporating more restaurant-style skills into my own home cooking. I’ve bought a kitchen scale to measure ingredients in grams; a mandoline to make my favorite coleslaw. I was gifted a stand mixer, and I’m convinced of the absolute and clear superiority of King Arthur’s flour, both bread and all purpose. Two weeks ago, I messed up my mental math and added too much water to my baguette dough, even though I’d been working on a starter from sage and lemon peels for days. The bread was flat, and I was pissed at myself, but, as my friend Ngofeen said, it was delicious, the lemon subtle but clear, and look at that crumb! A+ on the crumb.

For my mounted butters, including my Buffalo wing sauce, the “Keep Warm” function on our new electric range is the perfect temperature to let the sauce sit, even for hours, without splitting.

Learning these techniques, what they’re called and how to do them, is joyous for me. There’s pleasure in it, and not just the eating. When I get it wrong, I know I can and will try again. When I get it right? Like my pressure-cooked lamb shank over red lentils topped with parsley and a parsley foam (blanched parsley, blended, strained, mixed with 0.6 percent w/v lecithin and foamed with a whisk). Oh, honey! That’s a restaurant-quality home-cooked meal for under 10 bucks a plate. I beam with something like pride. My mouth pops with flavour, the cumin, the herbaceousness of the parsley, the almost nutty red lentil stew (cooked, of course, in the lamb stock from the braise, itself hearty with red wine, soy sauce and white miso).

In this house, that’s a good night.

This discussion of the proper use of French-style haute cuisine cooking isn’t just confined to those of us willing to triple-fry chicken wings and make foams at home. As The Bear and countless reality TV shows have demonstrated, the professional kitchen can be a horrifically toxic place. The recent announcement that Noma in Copenhagen, the—quote—“best restaurant in the world”—unquote, is closing, in large part because of the amount of unpaid labour that type of cooking requires to churn out its nightly dishes. The headlines all read things like “Is fine dining sustainable in 2023?”

The Menu was arguing that fine dining is not; there’s something rotten in the core. The Bear wonders what fine dining could look like when connected to community and with mutual care in the kitchen. Carmy and his sous chef Sydney—the stunning Ayo Edebiri—slowly win over the rest of the old kitchen staff with their talent, hard work and care. They’re hardasses, yes; as a teacher, I know what it can be like to expect a lot from yourself and others.

The Bear shows that food cooked in restaurants by the staff, for the staff, is called “family meal” for a good reason.

Fine dining, in my kitchen, is an experiment that usually works, but sometimes doesn’t. But these techniques, in my kitchen, are sustainable, precisely because they give me joy and sustenance. Most nights, I’m feeding no one but me and my boyfriend, but he loved that lamb shank and kept saying, “Wow, babe. Wow.” And I couldn’t help but smile.

Dessert: Family Meal

Super Bowl, 2023, H– is here, and I’ve made my chicken wings. Borrowing a Chinese technique from Lucas Sin, I use saturated potato starch as my batter and fry them three times in increasing oil temperatures, letting the crust set at room temperature between fries. When mixed with the sauce—that spicy beurre monté—they stay crisp for hours, even the next day. These wings, with techniques borrowed from restaurant cultures in France and Northern China, are the second best thing that day.

Walking through the kitchen as Devon makes a drink, I touch his lower back and say, softly, “Behind.”

“What, do you think you’re in The Bear,” he lobs my way, his eyes rolling, but his stomach empty and ready for wings. For H–, I’m making homemade pizza margherita, with dough that’s been cold-fermenting for 48 hours. I tried to dehydrate the full-fat mozzarella this time, leaving it out to dry for a day on a wire rack so it doesn’t exude so much water and make the crust soft and floppy.

I’m wearing the apron my friend Andrei got me for Christmas; it’s just like the one from The Bear. I have a tea towel at my left hip and over my left shoulder. The pizza is beautifully charred and rich and I couldn’t be happier. The wings, crisp and bright and spicy. We watch the game and, as always, play a game with the commercials, each picking a theme (“America!” “Equality!” “Women!” “Pets!”) and counting how many ads fall into our category. I lose. H– wins, as ever.

I don’t work in a restaurant. I don’t want to. The time I put into cooking is nourishment for me and my friends. It’s camp, yes—my dumb apron and my little scale—throwing flour on my fancy cutting board like in a French bakery. These techniques, learned from YouTube and Top Chef and The Bear, make me closer to the cook I want to be, better able to nourish my body and delight my friends. My food was the best thing that night.

My friends were the best best thing that day. This is my family meal.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra