Content note: This review contains a discussion of mental health, sexualized violence and trauma.

“There is nothing writing cannot cure. As soon as one is almost well, one becomes able to write—writing is the deep breath before full recovery.” —Lai Hsiang-yin, as quoted by Li Kotomi in Solo Dance

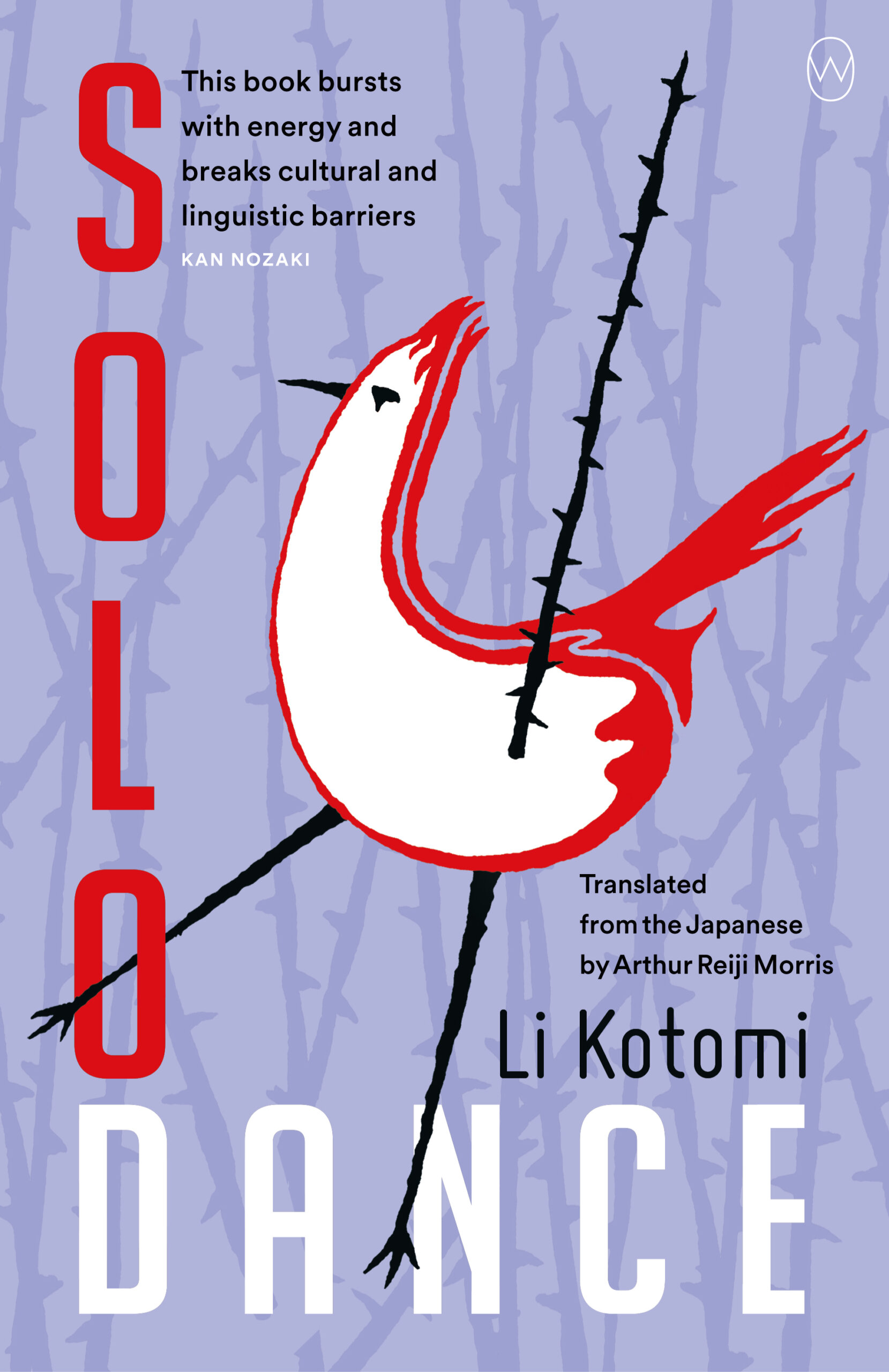

Loneliness is a sentiment that defies borders and linguistic barriers, as made evident in the Japanese novel Solo Dance by Taiwanese-Japanese author Li Kotomi.

First published as Hitorimai, Solo Dance is now available to read in English in a translation from the Japanese by Arthur Reiji Morris. The book, Kotomi’s debut, follows the fictional story of a queer Taiwanese woman as she survives depression and early adulthood in the “queer desert” of Japan. This novel provokes discussion around issues of queerphobia, mental health, sexualized violence and trauma.

Credit: Courtesy of World Editions

Solo Dance has received widespread acclaim in Japan, earning the Taiwanese-born author the prestigious Gunzō New Writers’ Prize for Excellence, an award previously won by the likes of Haruki Murakami. Readers are introduced to Cho Norie, a 27-year-old woman who struggles to live her life as an office worker in Tokyo. The thought of death is constantly on her mind, following her as she clocks in and clocks out at the end of each workday.

“While she still had breath in her lungs, she would do her best in life, yet should it ever reach that point where it was no longer bearable, she would choose death without hesitation.” Norie feels as if she does not fit in among her co-workers, nor does she know the right thing to say in the presence of others.

Readers come to learn that Norie’s experiences as a social outcast began at a young age while growing up in the rural Changhua region of Taiwan, where she was known by her birth name, Yingmei. She has long preferred the comfort of books and stories to other people. As a child, Norie is severely affected by the sudden passing of her first crush, a school classmate. This incident propels her to begin considering death and dying at a young age. As a means of processing this death, she begins to express her feelings of grief and sorrow by writing poetry:

“One day I will remember

Your story that ended before it began

Your face that lost all warmth before I could touch it

Your hardened blood that I failed to scoop into my hands

Just as the river runs towards the sea, the birds flock to the forest

Light flows onward; the way you left behind a pacifying melody for your soul”

Norie begins to experience her first queer joys as she gets older: dating, dreaming of a shared future with a partner and forming friendships with other lesbian and gay people. These meaningful connections offer her solace and comfort to persevere through her chronic feelings of loneliness and depression. However, after a violent event severely affects her life, her relationships to herself and others are completely turned upside down.

Norie’s traumas and depression continue to follow her as she attends university in the city of Taipei. She starts building a relationship with a psychotherapist and eventually begins chronicling her reflections in a journal. Readers glimpse her daily thoughts through first-hand written accounts documenting her poetic observations, the weather, reflections on medical appointments, interactions with university classmates and her eventual decision to change her name from Yingmei to Cho Norie and move to Japan. By moving to a new country, Norie hopes to disappear into a new life and leave behind what her friend Sho describes as Taipei’s “suffocating mass of grey clouds.”

“It was strange how writing about death had allowed her to keep living,” writes Li. For Norie, novels and poetry, as well as her own writing practice offer a lifeline. Throughout the story, she expresses a reverence for Taiwanese, Chinese and Japanese literature. These are the literary canons on which Li’s book builds. The writings of late author Qiu Miaojin (1969–1995), one of Taiwan’s most renowned queer authors, are particularly significant.

“Through her stories about self-loathing, death and suicide, Qiu’s books provide Norie with a tangible queer pathway to survival.”

As a teenager, Norie is fascinated with Qiu’s life, suicide and experimental books, which address the experiences of young queer misfits in Taiwan and abroad. During one scene, a line from Qiu’s book becomes the first words Norie recites to catch the attention of a love interest: “‘I hope happiness and health await you,’” she recites to Xiaoxue in their high school library’s reading room. After she flags her romantic interest, “the frozen space between them thawed.” In this moment it is clear how Qiu’s unapologetic writing breathes possibility into Norie’s world. Through her stories about self-loathing, death and suicide, Qiu’s books provide Norie with a tangible queer pathway to survival.

Thematic and craft elements from Qiu’s haunting works echo throughout Li’s Solo Dance. Within the novel, Norie notes the similarities in her life with that of Qiu’s. Meanwhile, Norie’s girlfriend Xiaoxue compares author Qiu’s short life and lasting legacy to the myth of the thorn bird, a bird that sings only once in its lifetime. Xiaoxue tells Norie about how the thorn bird spends its life searching for a particular tree, covered in barbed thorns. Upon finding the tree, the bird impales itself against the sharpest thorn in order to kill itself. In its last moments of life, the bird sings the most beautiful song, transcending the pain of its death and enthralling all.

Norie comes to the sorrowful realization that she has outlived her role model, Qiu. She decides that she wants to find meaning in her life before she dies, considering the lasting cultural impact of Qiu’s acclaimed work. As she contemplates these ideas, the thought of “blooming beautifully first … for a moment before dying … like the thorn bird” stays with her for a long while. She comes to feel a sense of urgency and artistic responsibility to write “the story of a solo dancer, alone in the dark.” Fittingly, this is an accurate description of this novel.

Solo Dance is a story with incredibly heavy subject matter. In all likelihood, it will be difficult for some readers to engage with, considering its inclusion of queerphobia, suicide ideation, rape and the forced outing of a queer character. At times, it can feel like too much all at once.

Li herself acknowledges the harsh seed of truth that lives within the novel. “The pain and suffering that Cho Norie experiences is very real,” says Li in an interview promoting the book. “That isn’t to say her experiences are based off my own, but I fully understand her pain and suffering. The only way for me to process and liberate these feelings was by writing this novel.”

Considering this is a translated work, I can’t help but wonder what the experience of reading this book would be like if I could read and understand Japanese, too. Would the writing be any less dark or heavy? Would it need to be? Regardless, I appreciate how Morris captures Li’s lyricism, providing a sense of beauty in the work, despite its bleak address of dying and depression.

As the book ended, I found the story’s pacing to be somewhat rushed in reaching its resolution. Amidst the intense subject matter, I felt there was more spaciousness surrounding the darkness of death when Li’s writing switched its craft approach from a third-person perspective to Norie’s first-person journal entries. I am curious to see how Li’s writing craft has developed and grown in her subsequent books, which have also been well received in Japan.

“In a society where the tradition of marriage is often expected, I learned it is common for queer people living in Japan to lead double lives.”

This novel provides an opportunity to consider the narratives of queer life beyond the bounds and limitations of Western-dominated English literature. As I don’t have any personal experience of growing up as a queer person in Taiwan or Japan, I was intrigued by the queer cultural elements Li included, such as the places where Norie finds community as she looks to build friendships through online forums, Pride parades and lesbian bars in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ni-chōme neighbourhood, which is said to be home to the largest concentration of gay and lesbian bars in the world. In a society where the tradition of marriage is often expected, I learned it is common for queer people living in Japan to lead double lives. This is seen within Norie’s friend group, who often go by nicknames inspired by their online alter egos.

Solo Dance’s biggest strength is its encouragement for readers to consider the power of literature in shaping life from the margins of society. Like Qiu and so many other authors before her, Li’s work may provide readers with the necessary sense of inspiration, representation and reason to continue living.

While at times a difficult read, this book still contains many truths and I have much respect for Li’s accomplishment in receiving critical acclaim in Japan for this poignant queer work, written in her second language, no less. I hope this novel will find a fitting audience in the English literary world, too.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra