Trans girls writing about Greer Lankton’s art have a tendency to make her work about themselves. It’s a sentiment I encounter often as I’m researching her life, and it’s certainly true that trans women are often accused of rewriting our saints to fit our pet theories.

That’s not to say that she made it easy for others to rewrite her story. Lankton was a wickedly talented trans woman artist who created life-size dolls based on cult figures such as Candy Darling, Jackie Kennedy and Divine. “It’s amazing how well she documented her life. I think she did that knowing that she wanted people to know who she was and to be remembered,” says Sarah Hallett, an archivist at Mattress Factory, a Pittsburgh gallery that houses a significant archive of Lankton’s work. “I think that’s one of the most powerful things about [our] archive. It really continues for her to tell her story the way she wanted to tell it.”

Lankton’s interest in art was piqued early. She was born in 1958 and grew up in the U.S. Midwest. She was a sissy, crafting her own dolls at a young age. At her peak, she was featured in groundbreaking exhibitions like New York/New Wave at MoMA PS1, alongside Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Mapplethorpe and Keith Haring. But her work is still widely unknown among wider, cis audiences. Largely ignored by mainstream art critics, Lankton’s story has fallen on fellow trans women and archivists to tell.

Still, Lankton may finally be getting her due: in April of this year, the Mattress Factory made their vast archive of Lankton’s work available online, creating an expansive, accessible resource for new generations to discover her craft.

Credit: Courtesy the Greer Lankton Collection, Mattress Factory Museum, Pittsburgh, PA

The Mattress Factory’s archive—made possible through a large donation by Greer’s parents in 2014—houses a staggering number of letters, diary entries, photos, original artworks and, according to Hallett, a large collection of human teeth.

However, a second archive exists. The Greer Lankton Archives Museum (G.L.A.M.) is based on the opposite coast in Los Angeles. G.L.A.M. is run by Lankton’s ex-husband, Paul Monroe. He commemorates her work by selling T-shirts and screening films inspired by the late artist. G.L.A.M. has a variety of celebrity endorsements, including Lena Dunham and Jemima Kirke.

Trans women rarely control their artistic legacies. Lankton’s parents, trans women, celebrity admirers and ex-lovers all paint their own picture of her life. Each storyteller owns the Greer they knew, but it’s impossible to paint a full picture of the raucous, beautiful, filthy artist without exploring her paradoxes. Her complexity is most clear in the way she talked about her sex change.

“Well, see, I always have the identity of being a transsexual,” she began in a 1995 interview with museum curator Carmen Vendelin, “I have all these arguments with transsexuals about this because there’s a whole school of thought that you should just forget you were a boy … there’s this other school of thought where you accept the fact that … you’re not really a woman, but in your daily life you pretty much act like a woman and do what women do, but deep inside you know; you don’t forget that you used to be a boy … I can’t actually say that I am a woman.”

In the same interview she recounted a nervous breakdown that led to a “horrible” hospitalization where she was put on Thorazine and told to make a choice at 21: “Be gay, or become a girl.” Lankton dubbed her surgery “the Kmart of sex-change operations.” She had just completed a few years of art school in Chicago and was about to move to New York.

In interviews, Monroe has stated he believes this ultimatum was made by Lankton’s mother. According to Monroe, her mother wanted “a solution,” while her father never said a word. “How could he not stop her?” Monroe recalled Lankton saying of her father’s silence. “Just lately, I’ve started thinking he didn’t protect me.”

When I spoke with Lankton’s artistic mentee, Jojo Baby, they told a similar story. “Her parents gave her an ultimatum one summer. They said either you get a job or you get a sex change and she’s like, ‘I hate to work, so I got the sex change’… it was performed wrong and she never could be penetrated. She said that she always looked for boys with long fingers.”

Who controls a trans woman’s bodily autonomy? There’s something less than triumphant about this gender journey. Perhaps this is why everyone tries to speak for Lankton, to find their own authentic version of her shifting identity and the “truth” of trans identity. In his remembrance, the critic Hilton Als pointed out she was the daughter of a pastor whose congregation helped fund her transition. “How could Greer ever repay them?” Als asked. Must she? How much do trans women owe the individual GoFundMe donors who snap at their post-surgery looks, asking for play-by-plays?

Once in New York, Lankton studied at the Pratt Institute. She began exhibiting at Civilian Warfare in the East Village with solo and group shows that brought her some notoriety. In 1981, her work hypnotized audiences at New York/New Wave. She’d barely recovered from her surgery and was only just starting her meteoric career at 23. She soon met Paul Monroe, a jeweller who ran a store called Einsteins in the East Village. Lankton began exhibiting her dolls in the shop windows. They married in 1987. Peter Hujar, Nan Goldin and David Wojnarowicz all attended the wedding. Two tiny dolls of Greer and Paul stood atop their wedding cake.

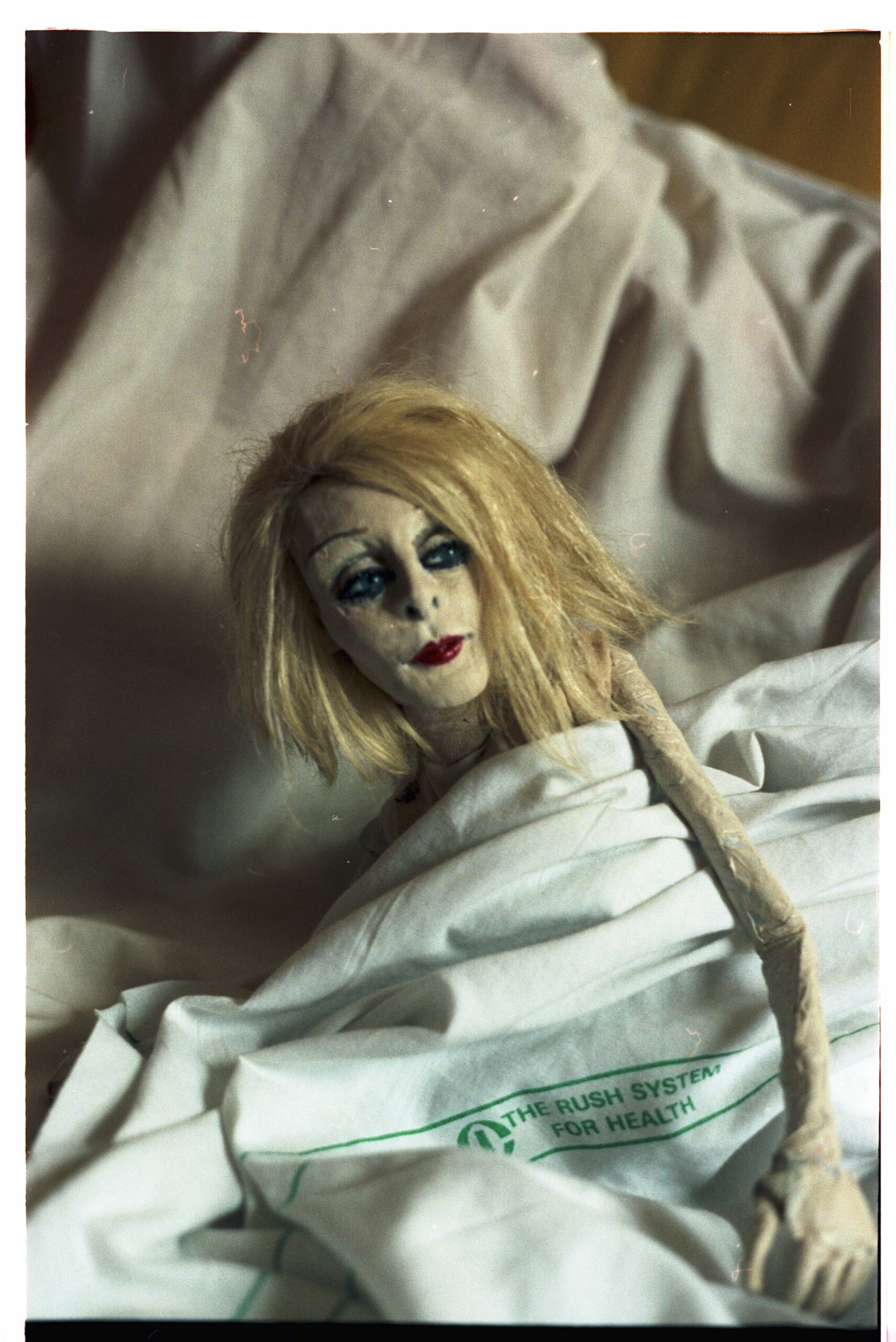

Around this time, Lankton assembled many of the dolls she’s most known for: Andy Warhol, Divine, Diana Vreeland and dolls based on people she saw in photographs or walking around the East Village, including Sissy and Princess Pamela (now owned by Iggy Pop). “They’re all freaks. Outsiders, untouchables. They’re like biographies, the kind of people you’d like to know about. Really interesting and fucked up,” Lankton told the East Village Eye in 1984.

Credit: Courtesy the Greer Lankton Collection, Mattress Factory Museum, Pittsburgh, PA

For most of her life Lankton struggled with heroin and disordered eating, ruminating on celebrity and the curves of her body. She modelled for friends Nan Goldin and Peter Hujar—often nude with her dolls. In her 2010 thesis, Karen Karuza stated it best: “We can clearly see Greer as one of her dolls.” That is, she too was constructed, both by surgery and anorexia.

Some of her work explicitly addressed her acts of transformation. “Some of them I change from like a boy to a girl or a girl to a boy,” she said. One of her hermaphrodite dolls gives birth to another.

Many of the dolls were wearable and Lankton would often walk around inside of them. Writer Gretchen Felker-Martin, one admirer of Lankton, remarked, “I think [it’s] so fascinating, for someone who so publicly struggled with anorexia to covet fatness and to use it to protect herself in public.”

To Lankton, the dolls were beautiful, living beings who evolved over time. They struggled with the same things she did: addiction, anorexia, dysphoria, love. Art critics often refer to the dolls as uncanny or grotesque, taking on an occult quality. But the dolls are clearly baptized in Lankton’s love. These are fabulous women with couture gowns and looks like stun guns. Defiant, gaunt, nude, corpulent—they laugh at our gaze. They’re over us. The dolls are a family, primping under their mother’s proud gaze.

In the ’90s, Lankton’s addiction worsened. She divorced Monroe and moved to Chicago to detox. Their divorce was finalized in 1993, though Monroe “insists that the pair never divorced and that Lankton’s mother forged divorce papers.” In letters and psychiatric evaluations from the Mattress Factory, Lankton stated: “Paul beat me up, threatens + tries to kill me.”

In Chicago, Lankton frequently decorated store windows with her dolls and artwork while mentoring Jojo Baby. The pair were introduced by their mutual friend Reagan, a lover of Lankton’s. They decided to meet for the first time at a bar. “I walked into the bar and there was only this suburban lady,” Jojo Baby recalls. “I walked up and we started to chat. ‘What’s a nice suburban lady like you doing in a place like this?’ She said, ‘I’m one of the girls too.’”

In one window display for a punk store called the Alley, Lankton scrawled a prophesy: “Hermaphroditic deity: ‘It’ lay in bed in a heroin haze. The make-up and hair, glamorous perfection, one thing that never let ‘it’ down … depression transformed into anger. ‘It’ would kill all the assholes who had stolen free entertainment laughing at the glamour only she-males possess.” Cis passersby beware. “Suicide or homicide,” the sign concluded.

Jojo Baby recalls Lankton’s time in Chicago as a difficult period. Lankton struggled with anorexia, attempted suicide and was sexually assaulted while taking out the trash. Jojo Baby knew about her eating disorder and always tried to get her to eat something. “I knew that she loved shrimp and broccoli, so I would always go to this Chinese restaurant,” they say.

But it was also a prolific period for the artist. The pair spent their time together working at a feverish speed while listening to Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God).”

“She pricked her fingers every now and then, and it was the dolls’ thirst for blood that brought them to life. So there’s a little bit of Greer’s blood in all her dolls,” JoJo Baby says.

Lankton’s career outlook was ramping up in 1995—she exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Arty and the Venice Biennial, and mounted her infamous solo show at the Mattress Factory. There was an intensity to this final exhibition, “It’s All about ME, not you,” a haunting one-for-one recreation of her living room full of Patti Smith memorabilia, headless crucifixes, troll dolls, hormone prescriptions and hints of addiction relapse.

Credit: Courtesy the Greer Lankton Collection, Mattress Factory Museum, Pittsburgh, PA

Lankton summed up her life in the accompanying artist statement: “I’ve been in therapy since 18 months old, started drugs at 12, was diagnosed as schizophrenic at 19, started hormones the week after I quit Thorazine, got my dick inverted at 21, kicked Heroin 6 years ago. Have been Anorexic since 19 and plan to continue and you know what I say FUCK Recovery, FUCK PSYCHIATRY … By the way I’m an artist and Andy Warhol was the dullest person I ever met in my life.”

Not long after the solo show opened, Lankton overdosed and passed away at 38.

Lankton’s legacy lives on in the work of trans women artists. Gretchen Felker-Martin is one artist who discovered Greer through a show at Participant Inc. “I first saw her work in New York … and these lovingly crafted simulacra of freaks immediately captivated me. I’m so hungry for images of deviant bodies.”

Jojo Baby also feels Lankton carved a unique figure in the art world. “I miss my time with Greer. I’ve never found the camaraderie or anyone else interested in the same work. I feel alone now … I went to a psychic and they told me, ‘Do you ever hear Greer’s voice when you’re working?’ and I said, ‘Yes’ and they said, ‘That’s when she’s the closest to you.’”

When I show cis people Greer’s dolls, they’re frequently enthralled, but have never heard of her. The trans girls I talk to all have stories. Zefyr Lisowski cut to the core of it in one of my favourite poems: “Listen: the more I punish myself, the more beauty I am allowed.” I said I wouldn’t tell my story, but I admit I too learned the value of self-punishment in the American Midwest: disordered eating and aborted attempts at heterosexuality, numbing drugs and an eventual move to New York. Before I knew much about Greer, I used to live down the block from her Pratt apartment. I bought baby’s breath from the nearby bodega in the late summer sun and prayed one day love would be easier for the girls.

Greer gave the girls the dolls we need. Her rage turns on true glamour. She built us a bedroom filled with freaky girls like us.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra