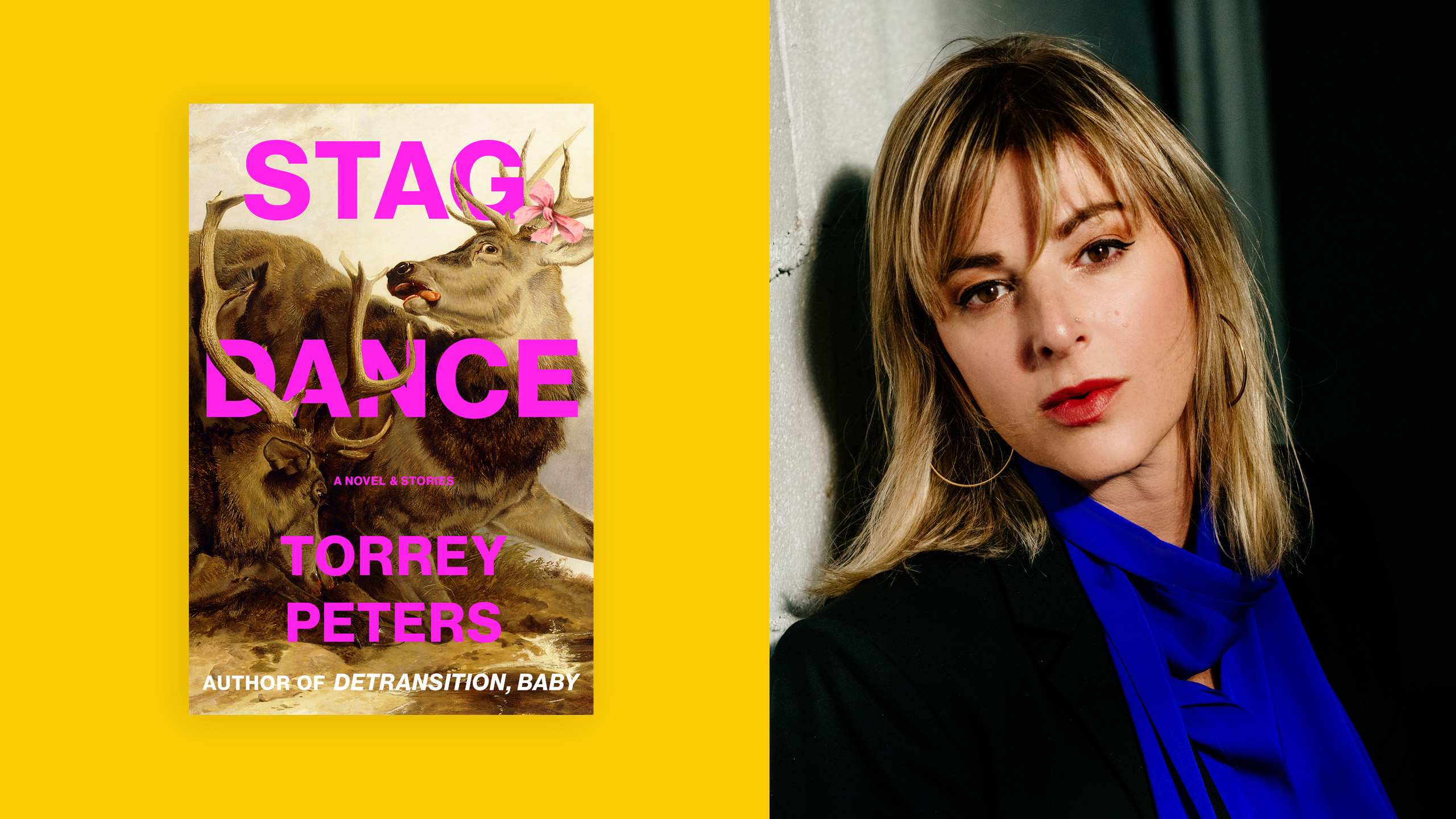

Of all the delightful surprises that await a reader in Torrey Peters’s latest book, Stag Dance: A Novel & Stories, perhaps the biggest one is this: a writer best known for penning Detransition, Baby, an endearingly hysterical, comic novel following the life of a flawed-but-lovable Brooklynite trans woman, has now given us a highly mannered, Cormac McCarthyian sliver of a novel chronicling the lives of transfeminine lumberjacks in the early 20th century. And I absolutely loved every word of it.

That novel is titled Stag Dance, and it is the centrepiece of Peters’s new book, which unites it with three other prior works. Altogether, the collection Stag Dance brings together roughly 10 years of work—two pre–Detransition, Baby novellas that helped establish Peters as an audacious and fascinating voice, and then a new novella and Stag Dance itself, both written after Detransition, Baby. Taken together, these four works bring into focus Peters’s substantial creative talents, as well as the through lines of what has so far been a remarkable career. They are not to be missed.

The title novel is based around historical dances that lumberjacks actually held in which some of them would be deemed women for the purposes of the night. It centres around Babe, an ox of a man who suddenly begins to piece together a trans identity when he takes the opportunity to be a woman in such a dance. The book is breathtaking for how Peters imagines her way into the consciousness of a person having a trans awakening long before any modern concepts or terminology around gender would have been available to him; she creates for him a masterful internal monologue that mixes actual historical lexicons with the strangeness and assertiveness of Peters’s authorial inspiration. It’s also the first time she has ever depicted a gender transition on the page.

The rhythms of Stag Dance bring to mind a work like McCarthy’s Blood Meridian for how it brought Shakespearean metre to the blood-soaked desert of the Old West. Peters’s novel is carried forward by the carefully conducted ups and downs of Babe’s voice, and at times the word choice is inspired. When Babe describes her groans of pleasure during her first female orgasm as “hadopelagic,” as well as her use of “degloving” as a metaphor for how her imagined vagina felt during that experience of intercourse, we are in the presence of awe-inspiring writing. It conveys the trans experience in ways I did not know were possible.

It’s easy to get carried away by the sheer aesthetics of this novel and forget the key detail: this is Torrey Peters writing about trans people. One of the startling things about Peters’s writing is just how aptly she apprehends the transfeminine experience in words, even when they’re the words of a lumberjack living one hundred years ago. To see Babe express what is now commonly called “gender euphoria,” for instance, is to feel a very meaningful space open up in my own brain as a trans reader, even though our experiences are so very different. To see what I mean, take a look at this moment, when a fellow lumberjack-cum-trans woman declares that she and Babe are “sisters” after getting made up for the dance, and Babe sees herself for the first time ever in a mirror. Peters perfectly expresses the feeling of release that comes with this transfeminine rite of passage:

I know, perhaps, that he meant it in jest—in reference to our matching mangled brows and the family relation inherent to that pairing. But it didn’t enter my ears that jestful way. The word enterest my head like a pin, to burst some terrible balloon that had been there always, obstructing clear passage. In the reflection, my face near to popped from bashful pride.

And yet, in Stag Dance, Peters is writing very much before words like “transgender” and “gender dysphoria” existed in any meaningful way. In this way, Stag Dance reveals one of the greater concerns of Peters’s project as a writer—namely, to address the ways in which the concept of “gender dysphoria” has prevented trans people from talking about the things that we really need to discuss. For whatever utility this one-size-fits-all term has brought to trans people as a unifying concept for our distress, it has also made it more difficult to disentangle the nuances of our own experiences as humans. In Stag Dance, Peters is very much undermining the centrality of this concept in order to trouble what she calls “the binary between cis and trans.”

An operative example is one of Stag Dance’s three novellas, The Chaser, a kind of campus novella involving two teenage boys away at a discount boarding school. Penned after Detransition, Baby’s big success, the story follows the seduction of the more masculine of the pair by the more fem, with either, both—or neither of them—being a closeted trans woman. Asking whether the seduction and the resultant romantic complications are driven by gender dysphoria would be absurdly simplistic, leaving out, at the very least, questions of maturity, human development, family, shame, loneliness, curiosity and desire. Declaring whether either of these characters is diagnosable with gender dysphoria would be like driving a sledgehammer through the elaborate emotional layer cake that Peters develops through her story—it’s to essentially impose a simplifying ret-con that renders moot everything beautiful about this tale.

In a similar way, gender dysphoria may be said to be the nuclear reactor that powers everything that happens in the pre-DT novella The Masker—but having said that, I’ve said nothing that isn’t completely obvious. The Masker is in fact an incredibly provocative, even potentially dangerous work, that is hardly about gender dysphoria, and instead is all about the consequences of it.

The Masker began its existence as a small-scale, self-published chapbook, a lovingly handmade, DIY piece that hearkens back to days long before people could print their own books on demand via Amazon. It was the kind of thing that an ambitious writer with very little to lose and everything to gain would bring into the world, and then—years later and extremely successful—hope that no one ever uncovers. The fact that Peters chose to place it before a Random House–size audience in the year of Donald Trump’s hyper-anti-trans second presidency shows just what a determined writer she is—and what a brilliant, necessary piece of writing it remains. (Great literature, it must be said, never gets old.)

The story involves a teenage trans girl with a fetish for sissification who attends a crossdresser convention in Las Vegas, there discovering two stark options for her future—to follow in the footsteps of a somewhat didactic older trans woman who assigns herself as her mentor, or embrace the hedonism of the utterly grotesque Masker, whose silicone woman suit is disgustingly sexualizing but also alluring. The novella, which mimics the careful structure and the subversive charge of a horror-drenched, gothic Edgar Allan Poe tale, engages the reality that prior to coming out many trans women process their untreated gender dysphoria through forced-feminization fantasies (unsurprisingly, these completely disappear during transition).

It needn’t be said what the likes of Donald Trump and associated hatemongers would make of such information, or even what some pearl-clutching New York Times reporter might. Even in 2025, it is still so easy to slander so much of the trans community by holding us up before a straight audience and asking, “Do you want your kids involved in this?” (As though the exact same couldn’t be done with any number of things that straight people regularly do.) A work like The Masker feels as impactful today as when it was first written exactly because Peters is unflinching and prophetic in how she looks at the parts of our experience that we probably least want to talk about in front of outsiders, if we want to talk about them at all.

With Stag Dance, Peters shows herself to be a writer who for over a decade has delivered a series of game-changing examinations of the inherent tensions, contradictions and joys of trying to exist in this world as trans. She has a knack for posing the questions that trouble us in ways that get right down to the root of the matter, and that show us that any answers will be extremely complicated and ongoing in their resolution. To put it plainly, her voice is substantial and necessary.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra