By now, the It Gets Better campaign — spawned by sex columnist/gay avenger Dan Savage in response to a seeming rash of gay teen suicides — is an international phenomenon.

The user-submitted videos on its YouTube channel number more than a thousand. Both US President Obama and Hillary Clinton have weighed in; an official response from queer Canadian celebs has been added to the roster. More videos pour in daily. And this is to say nothing of the splinter campaigns: there are, in fact, some It Gets Worse videos.

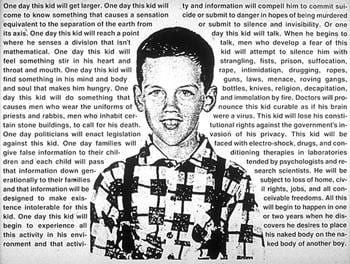

The more I look at these videos, the more I am reminded of David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (One Day This Kid…). I’ve seen it numerous times, in reproduction and “in the flesh.” And each time I see it, its brutal honesty and cutting simplicity shake me to my core (it’s one of the few works of art in front of which I’ve cried).

It’s a print: a grainy school photo of a young Wojnarowicz (he can’t be more than nine or 10), buck-toothed and gawky, smiling at the camera. The phrase “One day this kid will get bigger” appears on the upper left-hand corner of the page; that starts a litany of the systems of casual and institutional oppression that will be brought to bear on this kid as he makes his way through life. It ends with the phrase, “All of this will happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.”

Wojnarowicz’s work has been back in the news recently, after the Smithsonian pulled A Fire in My Belly, a 1987 video piece with religious iconography from its National Portrait Gallery. It only goes to show that Wojnarowicz still has the power to move people.

Wojnarowicz himself narrowly escaped a viciously abusive family life to wind up as a homeless, underage street hustler in Manhattan in the early 1970s. His artwork (film, writing, performance, painting, prints) channelled and attempted to exorcize the demons of his life; their chilling directness and hallucinatory power earned him success in the New York art world in the ’80s (he was included in the 1985 Whitney Biennial). He died of AIDS-related complications in 1992.

One Day This Kid… was made in 1990, and 20 years on, I can’t help but think that Wojnarowicz, in a single print, has eclipsed the totality of the It Gets Better campaign. For one thing, each of the horrors that Wojnarowicz enumerates are still true, 20 years later (as I read through it, I can easily think of news items from the past year that bear these phrases out). Given his art-world fame, one might be tempted to infer that It Got Better for Wojnarowicz. But that’s not the point, and he knew it.

There is much that is valuable about the It Gets Better project; I am heartened by its sustained success. But at its core, it makes an ultimately misguided argument: get through this immediate trauma so that one day, you’ll have the means to live a comfortable life, and those comforts will compensate for past suffering. This is a strange kind of hope to offer a teenager, and one of the more remarkable things about One Day This Kid… is that it offers no hope, and yet is not nihilistic.

It’s important to remember that it was made in the midst of the initial onslaught of the AIDS crisis, the heyday of ACT UP’s furious civil disobedience. Wojnarowicz can’t offer hope, because he knows that hope itself isn’t a guarantee, and more importantly, neither is it its own end. Wojnarowicz offers hope only tangentially, indirectly (certainly, we want This Kid to escape the text that surrounds and suffocates him). Crucially, the enumeration of harms to which This Kid will be subjected is meant to incite rage.

Finally, this is what I find missing from It Gets Better, and what I still find moving about One Day This Kid…. The former tries to soothe with the prospect of escape, and eventual isolation within domestic, urban comforts. The latter bears unflinching witness, and as such, is a challenge and a call to arms. Outrunning pain is only the first step; it’s what happens after that’s valuable.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra