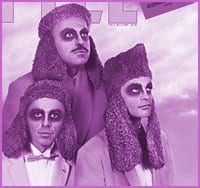

I think we’re considered sort of old masters of queerdom,” laughs AA Bronson, the surviving member of Toronto’s General Idea art collective.

The collective’s work is now showing in Vancouver at the Charles H Scott Gallery, in an exhibit that draws together the group’s multidisciplinary work on world health, beauty pageants, media, advertising, queer identity and much more. The retrospective spans 25 years, from 1969 to 1994, and captures an intersection of the campy, the confrontational and the subversive.

Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal first joined artistic forces when they started living together in Toronto in 1969. They were unaware then that their initially playful collaborations marked the beginnings of a huge body of work.

“The first thing we made were these fake storefronts with window displays and signs. We would have a little sign on the front door [that] said ‘back in five minutes,'” Bronson explains. “We were just entertaining ourselves. That’s how we developed our style.”

The partners’ ever-changing living arrangements soon affected their emerging style. “We were always living in various combinations at various times,” he recalls.

“A lot of our work came out of basically trying to figure out how to work together,” Bronson reflects. “We were continually processing both our private lives and our work.”

Beyond the mock storefronts, the group’s early work involved staging beauty pageants-and crowning at least one man as Miss General Idea-and subverting LIFE magazine with their own publication, FILE, from 1972-1989.

Though the collective’s bond was always fundamental to its work, Bronson and his teammates only publicly came out in the early 1980s, when they shoved their identity into the mainstream and refused to let go.

“We hadn’t been written about as being gay at the time; nobody had written about us from that viewpoint,” Bronson explains. “We were pushing people further and further [to] see how long it would take until somebody would respond.”

A series of images featuring fornicating poodles heralded the coming of their public queer identity. The poodles soon became ubiquitous and can still be found on many of their crests, and even in a later self-portrait.

“We always said we just heard barking at the door one day and we opened it and in they all rushed in 1981,” laughs Bronson. “The poodles were sort of a cliché and we made them as gay as we possibly could.

“It was only in ’85 that we got written about in terms of gay content or queer identity,” he continues. “Prior to that it was just considered embarrassing or something.”

Two years later, the collective subverted Robert Indiana’s LOVE icon and turned it into an AIDS icon.

It was “in such bad taste that we had to do it,” laughs Bronson. “It is sort of hard to forget once you see it. People were split down the middle and either hated it or loved it.

“There was a bit of misunderstanding in the US for the first little while. Indiana’s painting was taken to mean free love in the US while we thought of it as brotherly or universal love. So it originally got interpreted as ‘if you have sex you’ll get AIDS.'”

General Idea eventually exhibited its AIDS logo in at least 70 arts projects around the world and even projected huge images of it in public squares. Today, the logo covers one of the gallery’s walls. “In terms of issues, it is probably the biggest thing we are known for,” Bronson says.

The trio then turned its attention to ‘Playing Doctor’ and tackled the early AIDS medications (Azydothymidine or AZT), and their toxic side effects and high price tags.

“We did a big installation called “One Year of AZT” with five big pills a little larger than coffins representing a day’s dosage and 1825 pills on the walls representing a year,” Bronson describes. That installation is now in the National Gallery of Canada. Meanwhile, glass pills litter the floor of their retrospective exhibit at the Charles H Scott gallery.

General Idea’s work ended in 1994 with the deaths of Zontal and Partz from AIDS. The collective paved the way for queer artists in Canada and around the world at a time when there were few openly gay influences to draw from.

“Back then, it was very hard to figure out who was gay. Robert Indiana was, but Warhol had been the primary influence on us,” Bronson says.

Bronson himself now stands as a mentor within the art community, working in collaborative projects with younger artists, as well as producing solo works of his own (see sidebar opposite). “I’m the wise old man of queer culture,” he says proudly.

He is also one of three finalists in a project to create a piece of art on the subject of generic AIDS medications for Third World countries, to be unveiled at the G8 conference in London next year.

GENERAL IDEA EDITIONS.

A retrospective from 1967-1995.

Charles H Scott Gallery, 1399 Johnson St.

At the Emily Carr Institute, Granville Island.

Until Nov 7.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra