Barbie opens today.

But you already know that. If your social media feeds look anything like mine, you’ve been inundated with Barbie hot takes and clickbait for what feels like years now. The Barbie marketing machine has been unrelenting: I’ve heard so much about and seen so many clips of its powerhouse cast (that includes not only the irresistible pairing of Margot Robbie and Rylan Gosling, but also lesbian actor Kate McKinnon and trans actor Hari Nef … and Issa Rae and Simu Liu and, and … and). This film has been extra since its inception.

Quick refresher: Barbie is a cultural icon turned media phenomenon. She has been played with (literally and figuratively), used and abused, in pop culture and fine art and everywhere in between for generations. And this is not simply child’s play.

Queer filmmaker Todd Haynes used Barbie dolls as actors in his experimental musical short Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1989), where he deals with the biographical details of Carpenter’s struggle with anorexia (the film has since been banned).

There’s Hole’s 1994 album Live Through This, which used the Barbie font for the cover and commented, in part, on Courtney Love’s self-representation as a Barbie-esque bombshell whose actions were meant to subvert surface beauty and the constraints of gender. “Barbie is not your friend,” she famously quipped.

Photographer Nancy Burson’s Aged Barbie (1994) was commissioned for a book of Barbie images, but Mattel excised it from final publication. There are endless examples in every genre of artistic interventions employing all manner of tone and tenor to transform/translate the plastic cultural icon.

Cue the present moment: There has been an incessant stream of memes about and dreams for what Barbie, in Greta Gerwig’s feminist hands, might be and mean. So, are you fan or foe? Filled with BBE (Big Barbie Energy), movie tickets in hand … or uttering an exhausted “Kenough already!” and ready for the discourse to die?

Spoiler alert: Barbie discourse will never die.

Unsurprisingly, Barbie and friends have been queer and queered from the outset. The signs and symbols (see Henry Giardina and Alani Vargas on Barbie and queer coding) have been there all along, and queer and trans artists have produced a plethora of interventions and inventions through the years. Here’s a quick and quixotic tour through some of the gayest offerings.

Playing Barbie herself

Nina Arsenault’s “I W@s B*rbie.” Credit: Courtesy of Summerworks

In 2010, trans artist Nina Arsenault wrote and performed a one-woman show called I W@s B*rbie, an autobiographical account of the night she was hired to play Barbie at Canadian Fashion Week. This marked the launch of a Barbie-inspired fashion line on the doll’s official 50th birthday. In her script, Arsenault plays up the central irony of being cast as a plastic doll who has been accused of “fucking up the body image” of millions of girls across generations, while she herself has been transformed by so much silicone. Arsenault mused that to truly embody Barbie, she had to vacate herself for the night (hello, Ativan) and endeavour to be as plastic and perfect as possible.

In the show’s program, scholar Judith Rudakoff mused, “Is Nina a reproduction, a representation, a reflection or a reinterpretation? Perhaps a regeneration? A reinvention?” The piece variously reflects on the state(s) of embodiment, the performance of identity, and the nature of art/artifice/reality. In her 2010 interview with Xtra, Arsenault asserts that “I am the most real when I am on stage.”

Welcome to the dollhouse

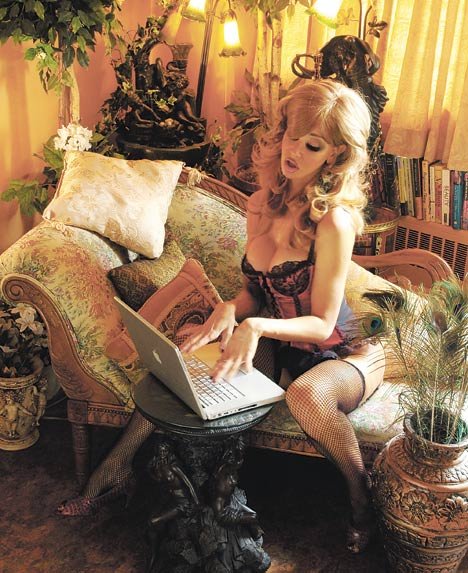

A still from “The Best Little Whorehouse in Toyland.” Credit: Courtesy of Robin Woodward

Robin Woodward is a designer and theatre artist living in Toronto. When she was still a straight-identified teenager in 1988, Woodward and her friends shot a porno “as a rainy day diversion”—on Betamax!—with multiple Barbies, plus a Ken doll fitted with a mini strap-on made of paper. The Best Little Whorehouse in Toyland would later make an appearance at a cabaret night dedicated to stuff queer artists made in their youth.

Woodward also co-owns, with her partner Ange Beever, the design outlet Barbie’s Basement Jewellery that offers all manner of glittery accessories and garments (now officially known as BBJ Pop Merch). Woodward came up with the company name in 1997. “I had quite recently exhumed a bunch of stuff from my childhood/teen bedroom closet and was struck by all the things I had made as a kid for my Barbies,” Woodward recalls to Xtra. “In particular, on the lowest-level of the minimalist Barbie-sized dollhouse my father had made for me, I had created a general store filled with art supplies, modelling-clay pastries, tiny bags of rolled-up cotton balls, packaged Ken shirts, etc. My studies and newly feminist ideas during university had made me uncomfortable with and dismissive of my love for those dolls, but finding all of the things my much-younger self had created made me realize that Barbie play was the primary outlet for my creativity. I thought invoking the name Barbie was a kind of reclamation.”

Super gay Barbie

Gunnar Montana’s life-sized art installation “Super Gay Barbie.” Credit: Courtesy of IG @gunnarmontana/

Gunnar Montana’s pandemic play recalls Woodward’s rainy-day diversion. A Philadelphia-based gay choreographer and performance artist, Montana garnered attention and acclaim during COVID-19 quarantine (we were all boxed up!) when, with collaborator Colin Burke and photographer Joe McFetridge, he turned himself into “Super Gay Barbie” replete with a seven-foot-tall box. Tagged with the catchphrase “Make your own rules, build your own box and always remember to accessorize!,” Super Gay Barbie’s accoutrements included, but were not limited to, a dildo, a douche bulb and a thong singlet.

Asked by Queerty about his motivations for the project, Montana claims that it was fun to collaborate with fellow artists during “bizarre” times, “fucking with gender norms and giving everyday society the middle finger.” Montana’s play evokes different sorts of super/action heroes via different iterations of the doll: the Leather Daddy Edition, Sexy Jesus, etc. (To see how the sausage was made, check out this behind-the-scenes video on Instagram.)

Barbie without borders

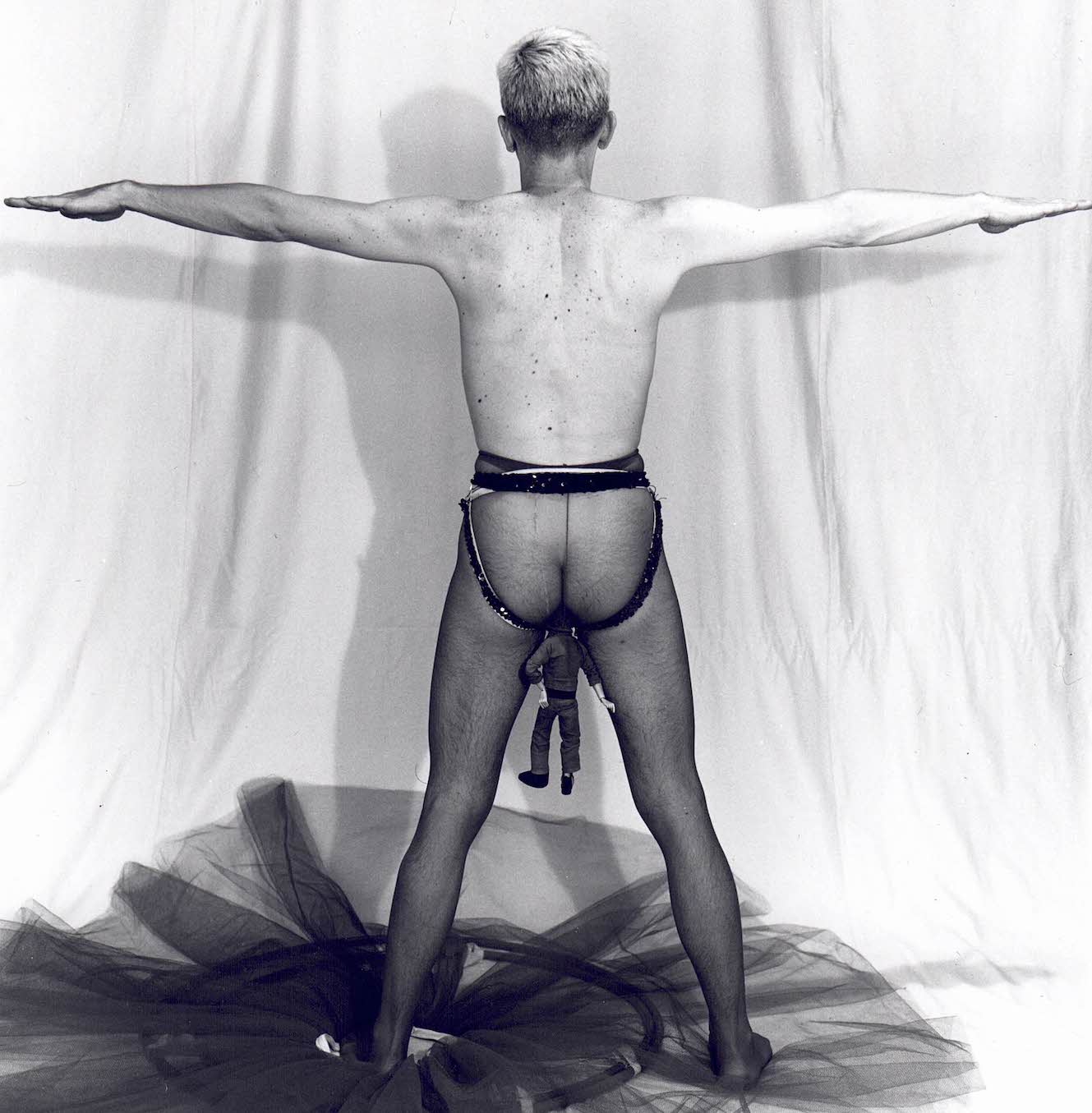

David Bateman’s “I Wanted to Be Bisexual But My Father Wouldn’t Let Me.” Credit: Courtesy of David Bateman

To promote his 1992 Fringe play, I Wanted to Be Bisexual But My Father Wouldn’t Let Me, performance artist and painter David Bateman roller-skated through Toronto Pride in a patio umbrella cocktail dress with a Ken doll stuck up his ass. He bowed frequently. Okay, it was G.I. Joe. What do you expect for a play that, in part, explores national identities? But Ken was often enlisted when Bateman couldn’t find enough of the action figure for the theatrical run. The original performance included the text: “you see, I never wanted to be a man, or a woman/ because I love borders/ crossing them, ignoring them/ borders between countries/ borders between sexualities.” In his 2018 residency at OCAD University, Bateman revisited the play and other pieces from the ’90s.

Dreaming differently

One of Wren Lively’s submissions to the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives’ “A Dreamhouse of Our Own.” Credit: Wren Lively

To coincide with Barbie’s summer release, the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives in Chicago recreated Barbie’s dreamhouse in their display cases, posing the dolls based on responses to their community call for LGBTQ2S+ stories of childhood play. Curated by Olivia De Keyser and designed by Steven Russell, the exhibition and accompanying zine, A Dreamhouse of Our Own: An Examination of Dolls, Play, and Queer Identity, showcase the ways in which creative play can dismantle conventional social structures and subvert traditional gender roles.

Plastic girlfriend

There is no shortage of queer reminiscences of messing with Barbie, of powerful memories of early play—whether safe, sanctioned, silly, secret, shameful (or some combination thereof). For my money, the most compelling of this genre is a moving personal essay by lesbian writer Kristen Arnett.

In her 2019 Buzzfeed piece, “Queering Barbie,” Arnett used Barbie figures to take us back to her girlhood experiences of gender, sexuality and class as expressed in her complex relationship with Barbie. A young Arnett embodied sundry desirous modes of being, having and wanting—of touching and being touched. “A good way to make yourself feel like you’ve got any kind of control over your life is to play with dolls,” she wrote, “because you can make them do whatever you want. Another good thing about owning Barbies if you’re a little queer girl is that you can look at their naked bodies and not feel like anyone will say anything weird to you for it, because if there’s anything we know about Barbies, it’s that they were manufactured for the purpose of taking their clothes off and putting new clothes on.”

Playing with Barbie was a way for Arnett to imagine her own future by fashioning it in her present. Even then, when sharing a room with her sister, the permission to dream was grounded in the reality that she would never inhabit a dreamhouse.

Dusty and Skye, the fashion-action dolls

In the mid-1970s, Kenner Products released the ill-fated dynamic duo Dusty and her Black bestie Skye. About the same height as Mattel’s Barbie, Dusty had smaller breasts, a wider waist, flat feet, movable joints and bendy knees. She donned sandals, sneakers and even cowboy boots. She wielded tennis rackets and fishing rods. Some of their limbs were even spring-loaded for the active throwing and hitting of all manner of balls (soft, golf, tennis). A realistic body, sensible shoes, sporty gear and action-oriented … ummmm, butch much? Often relegated to mere friend status, queers have long read Skye as more than: indeed, Dusty and Skye just might be an early butch-femme couple. Drag queen Trixie Mattel (named for her love of Barbie) is an avid Dusty collector.

SM Barbie

A scene from Maurice Vellekoop’s forthcoming memoir, “I’m So Glad We Had This Time Together.” Credit: Courtesy of Pantheon and Penguin Random House Canada.

Illustrator Maurice Vellekoop has just finished a graphic memoir entitled I’m So Glad We Had This Time Together. The book, in part, explores the conflict between his strict religious upbringing in a Dutch immigrant family in suburban Toronto and his queerness. In a chapter detailing how his emerging sexuality was shaped by ’60s and ’70s TV shows, young Maurice creates an SM-tinged sex scene with his friend’s Barbie and Ken dolls—the power dynamics imported from the Adam West–led Batman series. Published by Penguin Random House Canada and Pantheon in the U.S., Vellekoop’s memoir is due out spring 2024.

Since her 1959 debut, we’ve never stopped remarking on and remaking, reinterpreting and reinterrogating Ruth Handler’s creation. Barbie is a repository of history and fantasy. She’s the object of our desires and rejections. Barbie is the very definition of an overdetermined sign, signifying in sundry directions. Depending on who you ask, Barbie is the personification of harmful patriarchal beauty standards for women or she is the embodiment of global capitalism and mass production run amok or she is the epitome of queer camp. She is all or none or some combination thereof. And, and, and.

Why? Because, at heart, Barbie is all about desires and dreams, mirrors and reflection, play and role play. She’s the screen on to which we project our narratives: the stories we tell about Barbie are the stories we tell about ourselves.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra