Having grownup gay in a city there aren’t very many things I envy about my suburban sisters, except this one apparently fundamental event of rural teenage life: finding porn in the woods. I’ve been told that this is a common chapter in the narrative of suburban adolescent sexuality and I find it irresistibly romantic.

Like Lucy finding the magic wardrobe in CS Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles or Alice spotting the white rabbit, porn in the woods seems to be a key to a secret world of desire, excitement and experimentation. That world acts as a refuge from the chaste, smiling façade of everyday small-town life and its controlling and repressive ways. It’s this refuge that Kris Knight paints in his show of new work at Katharine Mulherin Contemporary Art Projects, entitled How We Quit the Forest.

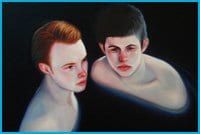

Knight presents a suite of paintings that are premised on the idea of the forest as sexual refuge, a world of secret swimming holes, comfy grottos and clandestine paths and clearings just beyond the curtain of the forest border. This is a universe untouched by the legal, social and cultural advancements of the Big City, where the toxic bigotry (to paraphrase Knight’s artist statement) of the small town forces its youth into the literal margins of the forest. It’s a world of teeming desire, covert and fragile, where the sweep of a pair of car headlights represents imminent danger. As this is a society that can’t exist by any kind of light, be it high beams or harsh daylight, Knight’s paintings are all plunged in the dark end of the spectrum: midnight blues, glossy blacks and deep forest greens. In the darkness the faces of the lonely, frightened, horny boys who populate this netherworld shine like the moon.

The characters of Knight’s rural melodrama all look the same: china-doll skin, pouty scarlet lips, glassy eyes, reddened button noses. There is a kind of every-lad quality to them, lending the paintings the surreal aura of fable. That generality is one of the strengths of the work as it allows the viewer an entry into what is meant to be a private space. There are weaknesses here as well. Some paintings are more accomplished and deliberate than others; there is some faltering drawing and careless painting here and there —which wouldn’t be an issue if Knight didn’t strive for a polished, seamless look.

But there are some lovely paintings: The Lone Wolf, in which a fit young lad in a fur cap and a Hudson’s Bay-coloured scarf howls against a pink backdrop; Branches Break, where two pale boys emerge like islands from a pool of deep Prussian-blue water; The Lull, which captures that charged uncomfortable pause where the intimacy of a conversation can lead to… other things.

In its best moments How We Quit the Forest comes off like a pop song: direct, yearning, accessible. Certainly Knight’s titles — Long Way Home (for a Ghost Like You) — sound like something off of an old Smiths’ album. At the end of the day I feel like, despite the toxic bigotry and the “small-town hell” (according to the artist’s statement), there is a lot of nostalgia in these paintings. However painful the circumstances that provoked them might have been, there’s nothing quite so electric as stealing that first awkward kiss and that first fumbling grope in the basement or in the forest, away from the prying eyes of authority.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra