Hanna Johansson’s award-winning novel, Antiquity, follows a lonely woman in her thirties whose desire for an older artist, Helena, leads her to spend a summer on the Greek island Ermoupoli. After the unnamed narrator interviews Helena in Sweden, she wedges herself into Helena’s life, part friendship, part work, part desire. Helena eventually plans a trip to Greece in order to relax, and the narrator wedges herself into that too. Also present on the trip, though, is Helena’s teenage daughter, Olga, whom the narrator initially sees as an obstacle to her potentially romantic intentions with Helena.

What ensues is a twisty web of lust and desire told by an unreliable narrator whose objective within this family dynamic seems unclear—even to the narrator herself. Antiquity brings up questions of longing, narrative and memory, all filtered through a queer lens.

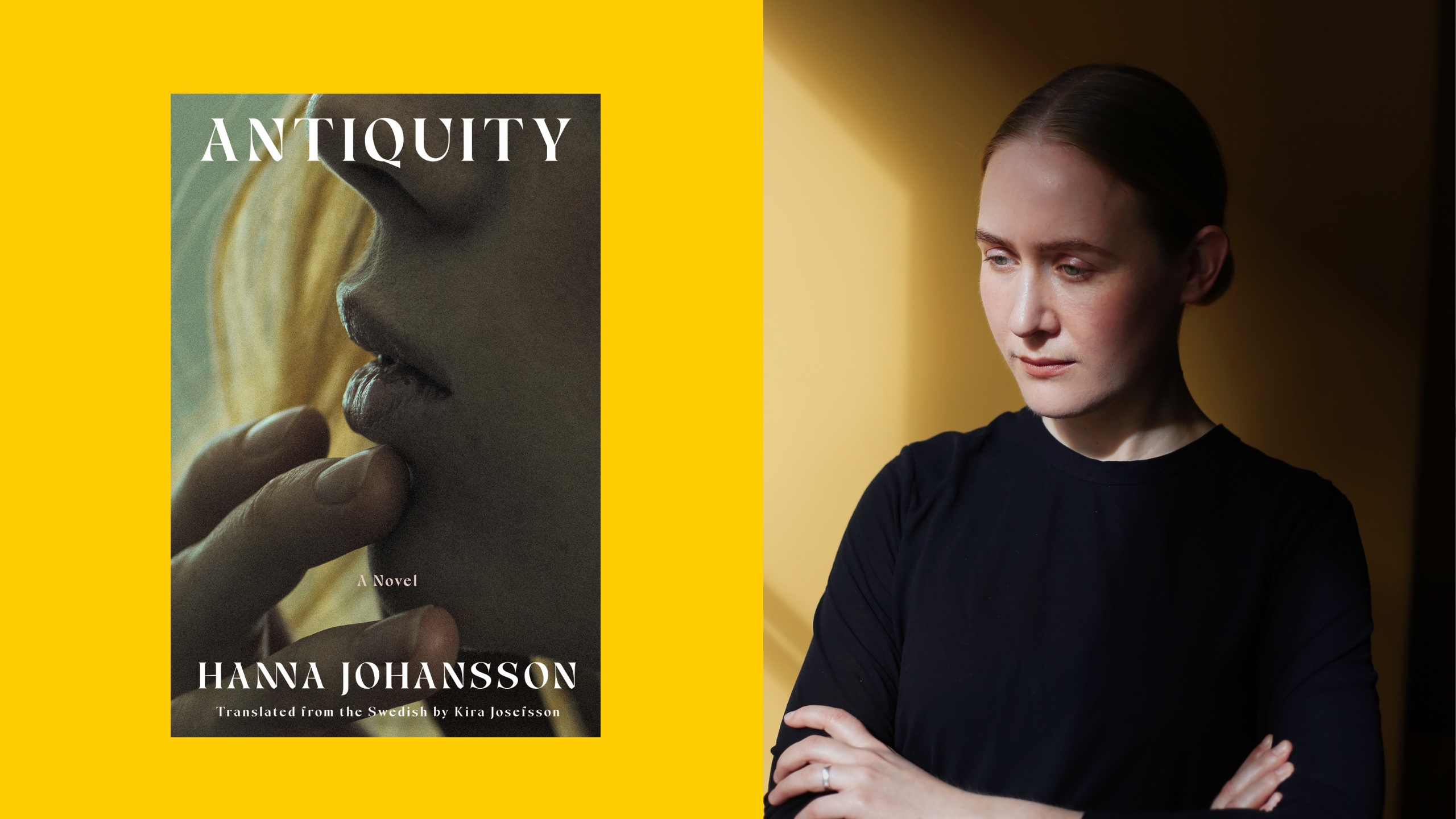

Antiquity was originally published in Sweden in 2021, and an English translation was released earlier this month. This translation was brought to life by Kira Josefsson, a process that Johansson describes to Xtra as “lovely.” Johansson is currently working on a second novel, which she describes as a “David Lynch movie directed by Éric Rohmer.” She speaks to Xtra about Antiquity’s English-language release, her interest in guests who overstay their welcome and unreliable narrators.

I’d love to hear about your inspiration for Antiquity.

I’ve always felt really drawn to stories of triangles and romantic stories, but also those about a guest who overstays their welcome. I read The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst when I was in my teens and I really fell in love with the concept of someone just kind of moving in with a family and staying for too long. Those kinds of stories I was really inspired by. It’s a fun way of following someone who’s peeking in. Another thing was that I spent some time in Ermoupoli and I was fascinated by the architecture of the city and aesthetic references from antiquity. I wanted to describe that place.

Tell me more about the structure of the book. It’s almost vignette-like and has very little dialogue.

I was really obsessed with the beginning of the novel, almost to a fault. I was working on the first part of the book for such a long time, and trying to figure out what would happen next. I wanted the structure to reflect the theme of trying to narrate your own memories and life. Making it feel really nostalgic even as things are happening. I love that you bring up the dialogue—that was also very important; I wanted there to be a little sense of doubt about what’s actually being said. Everything is filtered through this narrator whom I think of as a somewhat unreliable narrator. You very rarely hear people speaking in their own voice, which is also something that happens with memory. She’s in the process of creating this memory for later.

I love the interiority of it. As a reader, you wonder how much we should trust the narrator and how much she has manipulated the situation.

She’s really anonymous in a lot of ways. You don’t know much about her background. She’s sort of a chameleon or looking for own reflection in other people. I read Lolita, a very well-known, unreliable-narrator novel, where I feel like the narrator might be manipulating the reader a little more consciously. I think the narrator of Antiquity is almost manipulating herself. She’s almost aware of things, but she’s a little delusional.

I like that we don’t know much about her because you can see the ways in which she gloms on to other relationships—like the one between Helena and Olga—and even with other characters in the book, like her friend Josef and his boyfriend Alain, clearly looking for some sort of family, but also being unable to open herself up to create those relationships.

She seeks out this familial closeness with Helena and Olga, which is closer to a nuclear family. She’s looking for a mother figure in Helena. And I think that the relationship she has with Josef and Alain has the potential to be a chosen family. She has this friend and he has this boyfriend, but she’s incapable of making it work. It’s a really pessimistic novel in that sense because there’s no vision of queer liberation. I was preoccupied with friendship and the feeling that you have to be the number-one person for everyone at all times.

Throughout the novel, you explore mothers and motherhood using first the relationship between Helena and Olga, and then later through the narrator’s relationships with them both. The narrator sees Helena as a mother. With Olga, she takes on a mother role. Then there’s the whole queer element to it as well, which really feeds off ways lesbian relationships have been historically seen in culture.

Toward the end, the narrator almost weaponizes lesbian history in a really problematic way. I thought a lot about how motherhood is so sacred in a lot of ways and there’s so much emphasis on relationships between mothers and daughters. I was interested in how privileged that relationship is and how taboo it is to have a bad relationship with your mother. I was curious about exploring that taboo and also the fact that it is very weird that in lesbian relationships that you’re often taken for sisters.

Reading the first half of the book, you think something sexual is going to happen between Helena and the narrator—and then there’s that shift to the narrator’s focus on something sexual with Olga, who is a teenager. Why did you decide to incorporate that sudden turn?

I wanted to explore the way she handles wanting someone and they turn you away. The narrator is there and realizes that she’s not as desired as she would like to be and instead of just going home, she finds a way to stay in their life. She’s like, so if I can’t be her daughter, I have to take [Helena’s] place. I have to make a mark here. That was the logic behind her decision to [focus her desire on Olga] . It’s not healthy. I think her desire for other people doesn’t have that much to do with them.

I’m so glad you mentioned that because desire operates in so many interesting ways in the novel. Obviously, desire comes out of some sort of sexual nature, but it feels like the narrator is trying to make desire transform her into something else.

I was interested in exploring the power struggle or the sense that the narrator constantly feels very powerless and doesn’t realize when she’s the one in power. There is an obvious power imbalance between her and Helena at the beginning when she’s working for her. When it comes to Olga, the power imbalance is very clear. She’s older and Olga can’t go anywhere. She’s sort of trapped there, whereas the narrator can leave; she’s an adult. But the narrator doesn’t see that she has power in that situation. She sees it as the way that Olga has power as Helena’s rich-kid daughter.

There’s a scene when the narrator mentions an older man she often sees on the dock and what attracts her to him is that she thinks he’s truly alone, perhaps in the same ways she is. But also in that instance, she mentions that her curiosity about him stems because she thinks he’s also gay, but in a way that disgusts her. How does that reflect on her own queerness?

I do think that she’s a person with a lot of shame and someone who doesn’t have a lot of solidarity with other queer people. I feel like she has this image of herself as a tragic hero, to the point where the idea that you could be in community with other gay people is not attractive to her. She really is a bad gay.

Why was it important for you to explore queer characters for your debut novel?

Mostly because that’s close to me. I explore so many queer characters in my everyday life, in the group chats. I think that was just a reflection of how I live and what I like to read. In many ways it was the kind of book that I would want to read myself.

How did it feel winning Sweden’s Catapult prize for Antiquity?

I love awards season [laughs]. When you write your first novel, you’re kind of no one. So it’s nice that I got some recognition a while after it came out. The year that I was nominated, it was still COVID, so everything was really shut down, but I became really good friends with the other writers. We couldn’t have a proper party, so we hung out with each other. That’s been the best thing that happened since this book came out — that I got to know the other writers.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra