Sarah Blakley-Cartwright’s Alice Sadie Celine might just be the sexiest and cruellest book of 2023.

After a local performance in a production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Alice, a burgeoning young actress, ends up in the bed of Celine, the mother of her childhood best friend, Sadie. What initially might be a one-off roll in the hay ends up becoming a full-blown affair between the two women, both of whom are terrified that Sadie might find out. Sadie, on the other hand, is on her own journey. She’s attempting to forge a life outside the chaotic one she experienced growing up with Celine, a feminist theorist rock star who insisted on living a non-traditional life. Sadie is also navigating understanding her own sexual autonomy when trying to decide whether to lose her virginity to her longtime boyfriend Cormac.

As their affair deepens, Alice and Celine grapple with their own growing pains—Alice tries to decide whether or not she has what it takes to make it as an actress, or if she even has any talent at all. Celine, whose illustrious academic career has stalled, tries to think of what she can do to make a splash once again. They both find a kinetic energy in the sheets (it’s hot!) and when it all comes to a head—between all three of them—a delicious cruelty erupts, changing their relationships.

Blakley-Cartwright previously wrote the novel Red Riding Hood, and has worked as an editor. In this novel, she deftly explores sex and sexuality, feminism, motherhood, relationships between women and the particularly poignant cruelty we can inflict only on the people we care the most about. She spoke with Xtra about creating the triangle of Alice Sadie Celine, how she was inspired by Anne Sexton and getting rid of a male gaze.

What was your initial inspiration for Alice Sadie Celine?

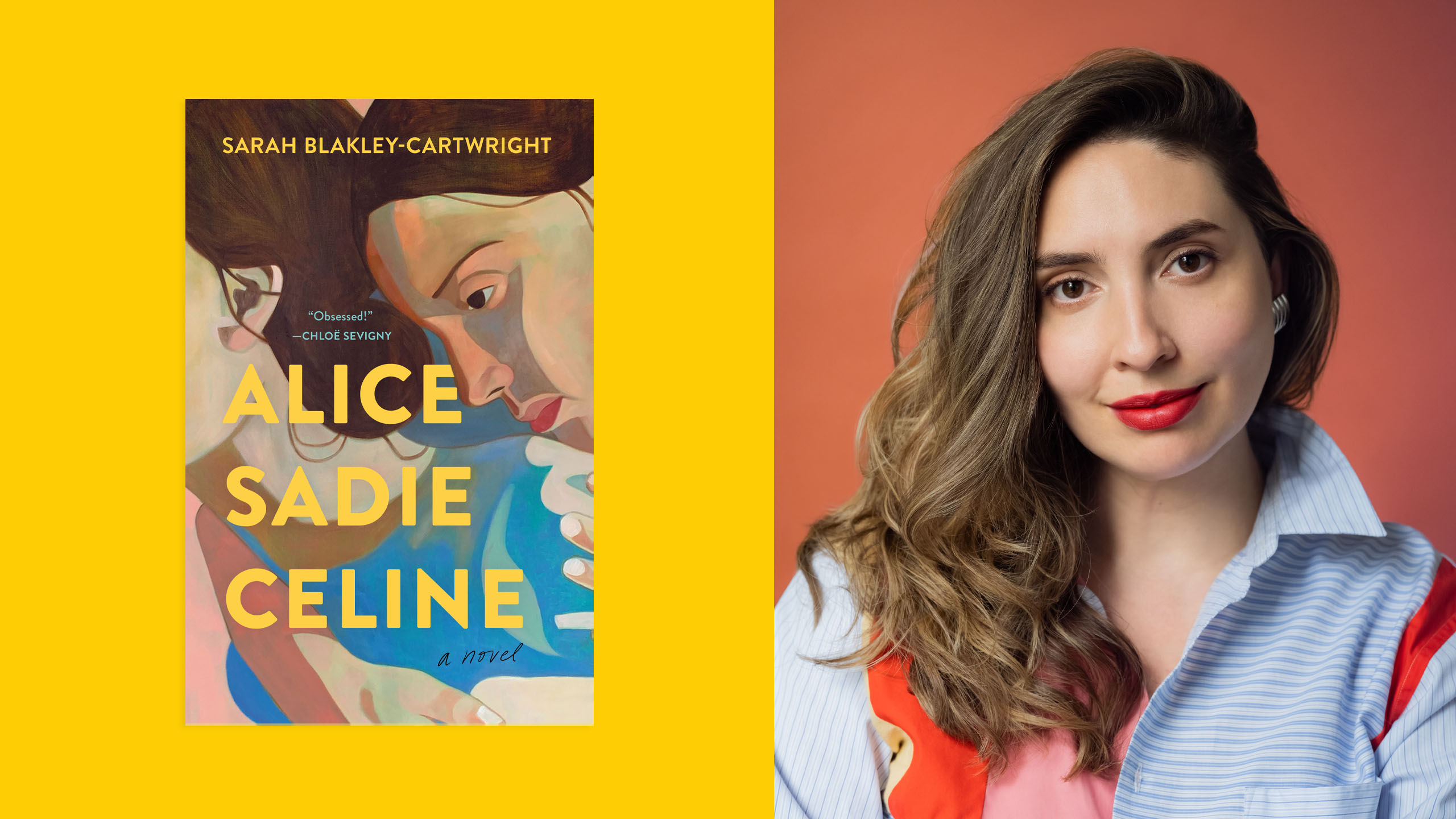

The first thing that came to me on day one was this triangle, this closed triangle, a mother-daughter relationship, a friendship and a love relationship. And that alone could provide everything I needed for the story. I’m not a writer who’s great at plot. That’s not my first strength. So that was really wonderful for me because I realized that just the threats to those three relationships could be the organizing principle of the story. And I think that’s part of why the cover is what it is in the end, why there are only two people on it—the entire architecture of the novel is around the fact that there are always two. It’s always a mother-daughter, a love relationship, a friendship—and one person is left out of the embrace.

I’m interested in the ways you explore queerness and feminism throughout. How did you go about thinking about those concepts in the context of the novel?

I think Celine uses feminism to justify her narcissism. She actually came to me on minute one too, and she was such a whole character. Women in their forties and fifties can feel so unseen in society. She’s so determined not to be dismissed that she thrusts herself into the centre of everything. But I do think her activism is very partial. It’s mostly in service of herself. She relates her experience with everyone else’s. If she’s feeling something, then everyone must be feeling it as well.

Sadie, on the other hand, really wants to protect her body by not sharing it. She doesn’t want anyone writing all over her body. Sadie is much more normative. Her mother sees every social, legal, familiar structure as a punitive kind of matrix, forcing us to adhere to heterosexual standards of behaviour.

In the novel, sex is really important. I think the daughter is really trying to work through her mother’s sexuality to get to her own. She feels fundamentally disconnected from her body. As someone who gave birth to a daughter last year, it felt more important to me than ever to see women enjoying their bodies on the page. I think especially in an era where reproductive freedoms are under such threat, it also felt important to me to reaffirm that a sexual body is nothing to be ashamed of.

Despite being a heterosexual couple, I feel like Cormac and Sadie’s relationship is very queer in the ways they emotionally interact.

I really wanted to explore women’s identities and how much we will allow women to depart from those identities.

Sadie gets nurturing from Cormac that she doesn’t get from Celine. Sadie really wants her mom to be a mom. She doesn’t want her to be her friend, but Celine treats her daughter like a friend. She certainly doesn’t treat her as someone worthy of protection or someone that she needs to protect. And even Alice, she’s trying to get into the family. She’s almost a sibling by having this affair. She’s trying to be loved by Celine in the same way that Celine loves her daughter, in strange ways. Everybody’s going about it sideways, but we all go at the things we want sideways. In a lot of ways, Celine, with this affair, is trying to close the gap between her and her daughter. Of course, Sadie is trying every day to widen the gap between herself and her mother. And I think the affair was really useful. It does both—brings them closer in a pretty wild way, but also drives them apart.

I never put Cormac in that closed triangle, but I love that you’re bringing him in. He’s really a participant. He is kind of bringing her up in a way. She’s coming of age thanks to him.

He is the stability that she’s craved for so long.

There’s a line in the book that essentially says, “Convention for Sadie had the ring of the exotic for her.” I grew up with a very unconventional childhood: I had two single parents who had never been together and who had gotten accidentally pregnant when my mother was 43 and father was 32. So for those of us who were raised that way, I feel like convention can sometimes sound good. I think all of us long—like Sadie—to have an itinerary, a route. And then also sometimes like Celine, we wake up and think, “I’m going to throw a bomb into all that.”

I don’t think identities are as established as we like to think.

I felt very drawn to Alice throughout a lot of the novel because both Celine and Sadie are so undermining of her constantly. So it felt so euphoric when Alice achieved success.

Something that was important to me is that she’s been dismissed from the beginning. I think she does have genuine self-doubt, but she’s also just someone who’s much more able to express self-doubt freely than the other two are. The other two really like to believe that they know exactly who they are.

Alice’s convictions are less identifiable at first glance, but they’re no less strong. And while Alice expresses a lot of self-doubt, I think she may be the most solid of them all. It’s just that she’s very supple, she’s flexible, she’s easygoing, she’s curious. There’s something very intrepid about someone who allows herself to be caught up and carried. She’s not rigid. And that’s how she ends up in this relationship with her friend’s mother. I want to give her credit for that. It’s quite daring. She’s forced to meet herself head-on, and she goes for it.

I really wanted to write a sexy book. And I think Alice is a huge part of that. Alice is a person for whom things are easy and that’s just hot.

Actually, that’s the epigraph of the novel—the great confessionalist poet Anne Sexton has a line: “I lived like an angry guest.” I thought it really fit the novel because it’s kind of playing with that idea of, “Does everything have to be hard?” These three women, their lives are pretty good. They’re being quite fabulously hosted at the party of life and they’re unhappy in a lot of ways. And then they keep making themselves unhappy. And it’s like, why do we do that to ourselves in life? Why can’t we just enjoy the party? But then at the same time, it’s really hard to be a guest in life. You’re on other people’’s turf, living on their terms. You can’t just do everything you want.

I really loved that Alice’s sexuality never ends up being defined, especially in the context of both Celine and Sadie who are so staunchly one sort of thing.

I think Alice is the most contemporary of the three women. She’s someone who is like, “You can’t put me in a box.” People can try to box her in, but she has enough self-possession to be like, “I don’t need to define myself for anybody else.” Whereas the other two are really seeking to be like, “This is who I am.” The other two are always trying to put boundaries on each other. And Alice is free of some of that.

I feel like among women, male-perpetrated sexism is ever present. I think women often participate in patriarchal and sometimes homophobic apparatus. One thing I was thinking is that after all Celine has been through to get to this point [in her life] is her own daughter going to be the one who’s coming for her head?

Exploring motherhood and moms feels like the backbone of a lot of the novel.

I have a mother who was a big personality and had a big career. So I know this dynamic of Sadie and Celine. So much of everything is determined by our mothers.

I think that the sexuality of motherhood has been on my mind a lot, in the way that the pregnant body is both totally sexual and totally nonsexual. Of course, they go hand in hand in every way, but there’s just this idea of the female body always being inhabited

There are also very few men in the book aside from Cormac, who in some ways almost serves as a vessel for Sadie to discover herself. Why did you want to do that?

For me, there are next to no men in the book. There are no men of consequence in the book. I instinctively wanted to keep the male gaze out of it. Once there’s a man in the scene, I think you really start to see female characters through a different lens. You kind of appraise them differently. You can just be naked in a much different way. I feel much closer to women in my world.

Without getting too spoilery, I love how the ending changes perspective to let us know what has happened between the three women years later.

When I first wrote the ending, my wonderful editor, Olivia Taylor Smith, said she would take the book with the caveat that I would have to change the ending. Once I wrote my new ending, I realized that it let these very autonomous women live off the page. These three women could have some privacy, and the reader would appreciate not being led by the harness from checkpoint to checkpoint.

I rewrote the ending five times because it didn’t feel like what I wanted to say. It was kind of amazing to have a moment of really asking myself, “What do I want to say?” In the end, it felt important to me to show these women able to climb over the mountain past division … to offer an affirmative view of women and of human beings.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra