Adele Bertei has a habit of showing up where you least expect. From her time in the late-’70s No Wave scene playing organ in the Contortions, to founding the first all-queer-girl band the Bloods in the early ’80s, to singing as backing vocalist for Thomas Dolby and Tears for Fears later in the decade, her trajectory as a musician was consistent only in its unpredictability. Meanwhile, her late-career reinvention as an author in the past few years has revealed new facets of her personality: music historian in Why Labelle Matters and candid memoirist in Peter and the Wolves (about her time with Pere Ubu/Rocket from the Tombs guitarist Peter Laughner).

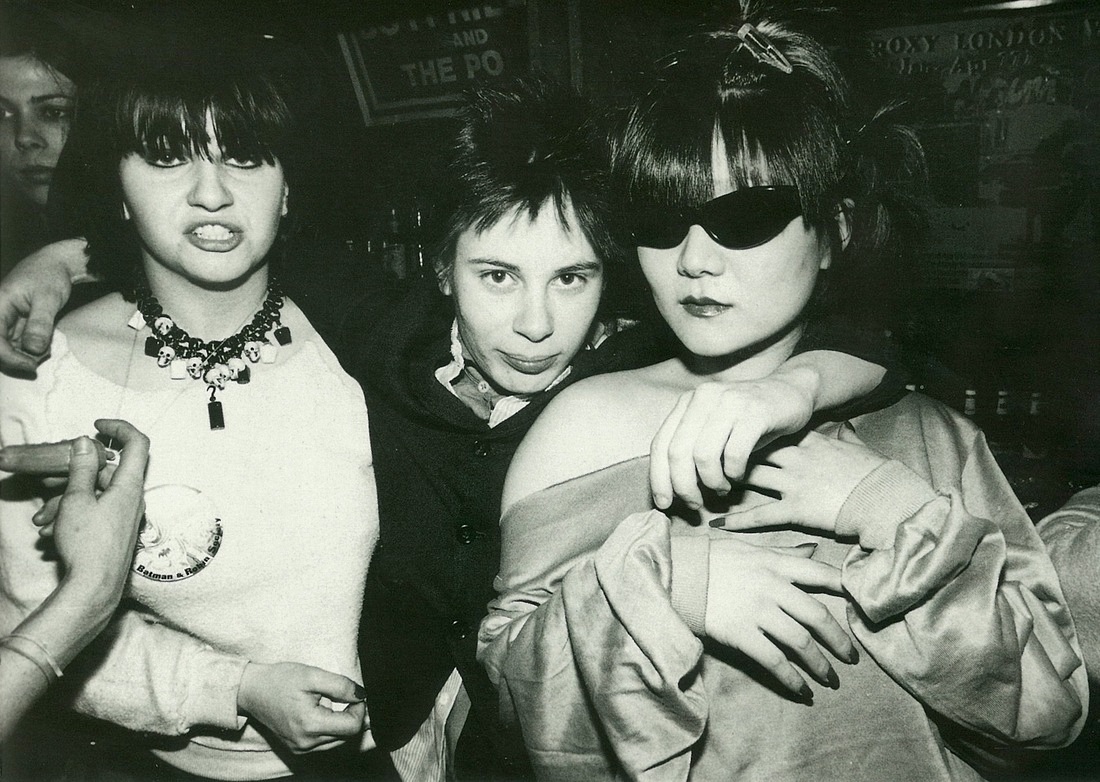

Credit: Julia Gorton/Courtesy of Ze Books

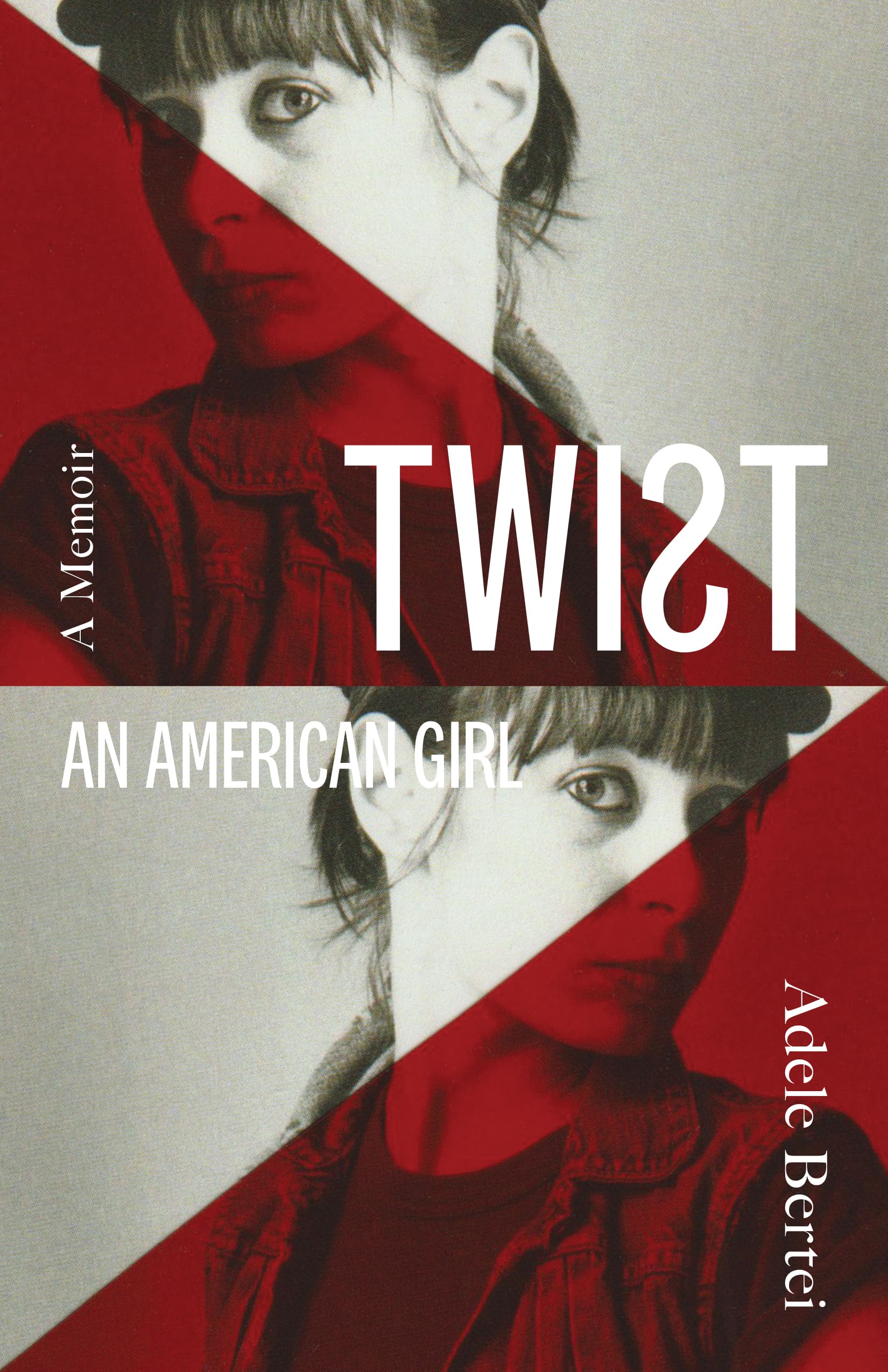

Yet more surprising still might be the story of where she came from. Her new memoir, Twist: An American Girl, out this spring, tells the story of Bertei’s childhood and adolescence, and is simultaneously both a deeply touching and starkly unsentimental account of growing up queer while trying to navigate an abusive home life, the foster system, juvenile detention and beyond. Throughout the book, we see a young Bertei fighting against the constraints of a system set up to fail her, sometimes even putting herself in life-threatening danger for scraps of hard-won happiness and a place to finally call home. “I wanted to write it from a very pure place of the child going through it in that time frame of the 1960s and early 1970s,” she says over Zoom from her home in Los Angeles. “In a way, [that was] to avoid the kind of adult analysis that would be put on it today.” Fellow queer musician Rufus Wainwright describes the book as a “harrowing voyage through the cultural tornado of America in the latter part of the 20th century as seen through the eyes of a thoroughly 21st-century girl.”

Bertei was eager to discuss how her own gay history might be relevant to our queer present and future.

Given the current political climate and the fact that you allude to an escalating war on women in the introduction to this book, did you feel a sense of urgency in trying to get this story out now?

I did, and actually, as soon as Trump was elected to office, I just felt like the guillotine was gonna come down on us all because he is such a blatant fascist, you know? So I felt it was really important for the younger generations of LGBTQ people to understand what we went through back in the ’60s and ’70s when being out of the closet was … y’know, you could basically lose your life over it! It feels so debilitating after having struggled for so long and having fought on so many different lines, with AIDS activism and all of the things we’ve gone through, to see this happening again. My one consolation is: gay people fight. We fight. The queer community will fight and fight and you will not succeed in oppressing us in the ways that you would like to, because we’re born fighters and will continue to be so.

One of the big talking points currently being used against queer and trans people is the whole “grooming” narrative, but your writing speaks to the impact that intergenerational queer friendships and mentorships have had on you. Do you worry about that dynamic specifically coming under threat?

Credit: Ze Books

I don’t, actually. The only thing I worry about is a commodification of identity politics that is feeding into the capitalist machinery. All of this branding feeds into the commodification, so they know directly how to attack us in each of our specific groups and how to sell to us. I feel that we need to become more aware of that and try to stop the divisiveness that’s happening within factions of our community, because the stronger we are together, the deadlier we are.

I guess one of the hopes in putting the book out there is crossing lines to see what our commonalities are, as opposed to what our differences are—to try and come together inside those commonalities to present a stronger front to fascism. I mean, who is the real enemy here? Not each other. It’s the fucking fascists. Excuse my language, but that’s who we need to be fighting against.

Swear all you fucking want.

[laughs] Thank you, thank you so much.

In the book you continually find yourself in groups of outsiders sticking together, whether it’s your fellow inmates at the Cleveland reformatory Blossom Hill, a hospital for the Vietnam vets, or the drag family you wind up in later on.

Yeah, it’s kind of the idea of family, and the family you’re born into not necessarily being a trap that you have to adhere to in terms of values, you know? You find your family with the people that you feel simpatico with, really, and that has always happened to be the outsiders for me. We live in a very punishing capitalist system, it’s very cruel, and part of my investigation in terms of writing is to try to really look into the threads of that systematic abuse that we deal with, and say—not in a pedantic way—that this happens to us all suffering under this system. How do we reach out to each other? Because I do feel like there’s a real spiritual yearning now, and we bury it because it’s uncool to think that way. But really, there is a spiritual yearning! We do want to connect, and I think a big part of art is us aching to make those connections.

The book is also, unsurprisingly, very musical, and it feels like there’s a song in the background of every important story beat. Are you someone whose memories generally have a running soundtrack?

Very much so! I mean, I’m sure there are moments in all of our lives where we can think of a specific song that moved us at a certain point and mirrored our emotional makeup at that time. I often talk about the ’60s song by Gerry and the Pacemakers called “Ferry ’Cross the Mersey.” I remember feeling the impending doom of the fact that I was gonna be a homeless kid by the time I was nine or 10 years old, and so that song gave me a mirror to what I was feeling, this longing for a place that I could call home, that actually loved me as well. So music has always done that for me, it’s mirrored feelings that I couldn’t necessarily express or parse out inside myself.

Is there anything you’ve been listening to lately that’s been leaving a similar mark on you?

I’m trying to think in terms of contemporary music … I’m kind of tending toward the more jubilant singers and performers. Lil Nas X, I adore, and I’m so happy to see queer people like him coming out and just being their authentic, wildly queer selves. It’s the wildness I remember when I was first going to gay bars in, you know, 1969. We were really letting our freak flags fly, as we called it back then, so to see someone like Lil Nas X, it’s so joyful. I just love Lil Nas X, what can I say? [laughs]

The music that inspires you is wildly eclectic. I also know from previous interviews that your own recording projects in the ’80s kept getting compromised by label interference. If you had had the creative freedom and the resources to actually realize a dream project, which of your influences do you think might have filtered into that?

I would have loved to have worked with a team like Wendy & Lisa, because I was very influenced by soul and funk music, as they are, but also their feeling for drama is so acute. I don’t know if you heard the last Grace Jones album, Hurricane?

Oh, I love that album!

That album is incredible! And they did that song, “Williams’ Blood”? That was Wendy & Lisa! So if I had been able to work with them and be my authentic queer dyke self … but that was not to be in 1988, you know? That was not happening.

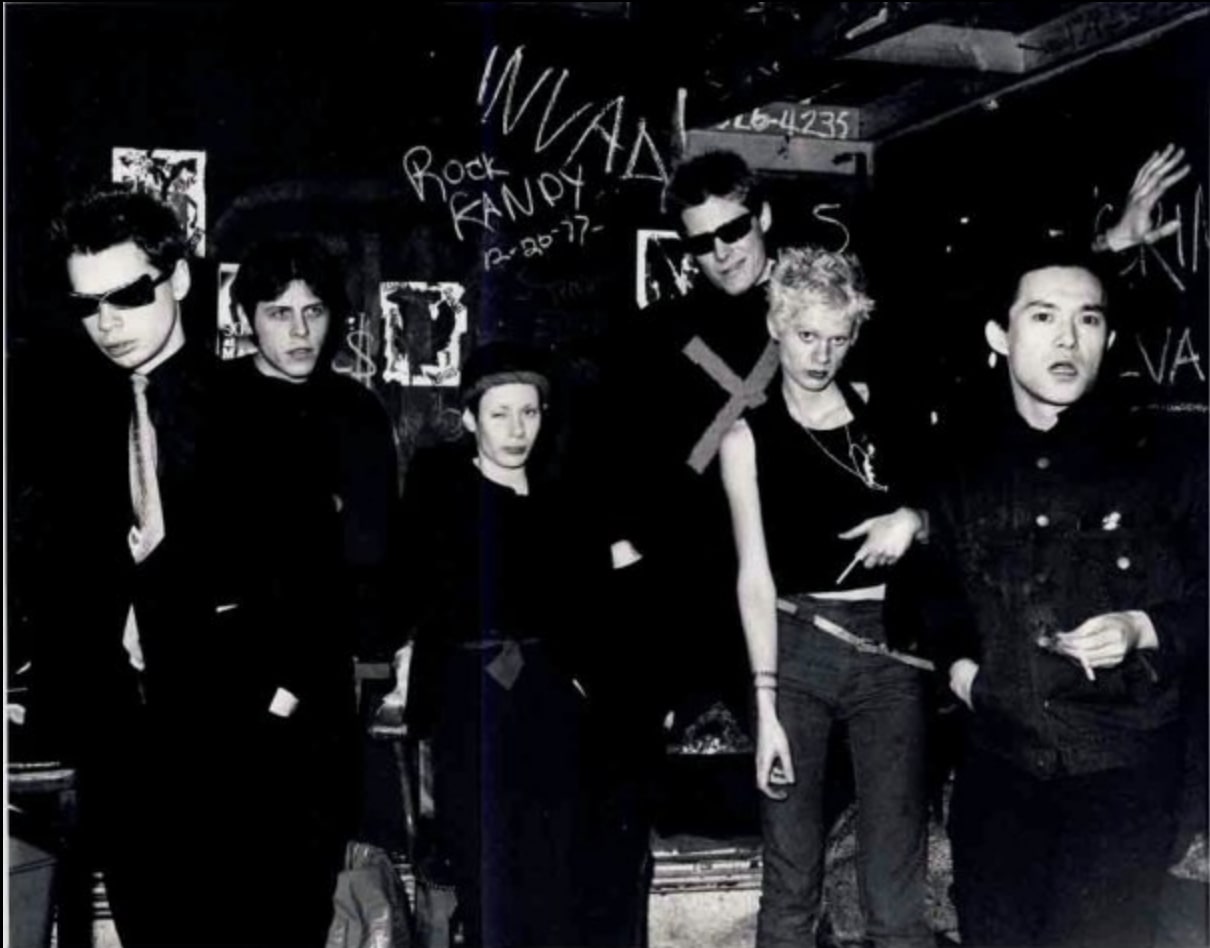

Credit: Patty Heffley/Courtesy of Ze Books

Do you see a continuity between those formative soul and funk influences and the music you wound up making in bands like James Chance and the Contortions?

In a way, we were approaching music from a very brutalist sensibility, like, let’s rip it all down, take the most primary, instinctual things about this music that we love and put it together in this mishmash. But also, my grandmother played honky-tonk piano in bars during the Depression, right? So she had a very Black sensibility in her piano playing, and when that was taken away from her by her husband, it really left a sore spot. So when I ended up playing organ in the Contortions—you know, you can’t beat rhythms on an organ, you press organ keys. Pianos you can beat rhythms out—so almost as an homage to my grandmother, I was going to beat the shit out of that organ, you know? [laughs]

Because I’m a Thomas Dolby fan who first heard of you through his song “Hyperactive!,” I’d love to know if you have any memories you’d like to share about working on that song?

I had a great time working with Thomas Dolby. I was living in London at the time, and he had a small boat, and I would meet him in Hammersmith and we would take the boat to Pete Townshend’s studio, Eel Pie Studios, which is right on the Thames. There was something very, very enchanted about it, you know? And people didn’t believe that I sang that high. People kept saying to Thomas, “Oh, you must have vari-sped her voice.” But no, I did sing that high, and I actually did a performance with him at that church in Islington [Union Chapel], and I sang it live about six years ago and people were astonished.

Do you do anything to keep your voice in that kind of fighting shape?

I sing in the shower [laughs]. Actually, I don’t know if I can still hit that high of a note! I mean, that’s up there, you know? But yeah, I’ve released two songs in the last six months, one is a protest song called “American Elegy” and it’s on all the streaming platforms, and then I just did another song called “Savage Is the Wolf” and it’s primarily a dance record. So, you know, one song at a time, I’m going back out there.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra