Jonathan Kelly (Robert Kersey) doesn’t fit in at his new high school.

His pale Goth look has the local bullies calling him a “fag,” not realizing that he really is gay; and his pompous history teacher derides him for his homoerotic reinterpretations of Egyptian mythology.

He does manage to attract the attentions of one boy, though — the tall, blond David (David Snyder).

Standing too close in the hallway, and making the first overt moves of a long and complicated flirtation, David wants to know if Jonathan is a witch. If he is, there are certain mysteries that David would like to explore with him — starting with a visit to the town graveyard, where a local Satanic coven has been harvesting skulls for a mysterious ritual.

Thus begins a rather unusual first feature, The Sacrifice, a “gay-themed horror film” by New Hampshire-based filmmaker Jamie Fessenden.

The film is the essence of DIY cultural production, shot for $10,000 over the course of a year on a single digital camera, a Panasonic DVX 100. It is Fessenden’s first feature, though he had already scored films for his filmmaker brother, Bret, and written a couple of screenplays intended for him.

While supportive, Bret wasn’t particularly interested in gay themes, and had his own projects to work on.

“I started writing The Sacrifice back in 2004,” Fessenden says, “and I was like, ‘Well, here’s yet another screenplay that’s not going to get made into anything.’ But my boyfriend, Erich Rickheit, was like, ‘Well, we’ve been hearing about these new digital cameras that aren’t too expensive, why don’t we just get one and make it ourselves?'”

Fessenden was skeptical, but Rickheit — the film’s eventual producer — persisted.

“He nudged me forward and we started putting out a casting call and we actually did find a bunch of actors who were willing to do it. We lucked out getting the camera used from a company that does digital media in the area. I happen to know people who work there, so I got a bit of a break on that. We paid for the rest of it out of our paycheques.”

For a homemade feature film with bottom-drawer production values, The Sacrifice has done remarkably well. It’s played several conventions and festivals in the US and is now listed on Amazon.com.

“A lot of people who focus on the look of the film have hated it,” Fessenden tells me, “but it’s played well for gay audiences. We played at a gay science fiction convention, Gaylaxicon, in Boston back in 2005. We didn’t even have a completely finished cut, but we got a packed room of about 50 people there, and they gave a standing ovation. They loved it, and chatted with us for about an hour afterwards. We’ve played well for Goth kids, too — we’ve shown it at some Goth clubs. Those seem to be our target audiences: gay and Goth tend to like it.”

Straight horror audiences, at events like the Necronomicon in Florida, haven’t been as receptive.

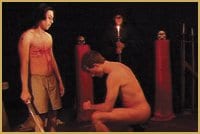

“We only had about 10 people there and they weren’t so enthralled — until the end. They loved the end,” he says. The film’s conclusion features both its most overtly homoerotic and horrific sequence: a blood-spattered ritual conducted in the nude.

Most of the film is much subtler.

Worried that young local male actors might not be comfortable “touching or kissing each other,” Fessenden deliberately underplayed the homoerotic elements in his first cut of the film.

“There were little hints, but you could miss that there’s any kind of sexual tension between them, and they never actually kissed. It was the boys themselves who said, after the Boston showing, ‘We’ve got to kiss in the movie,’ because they wanted the audience to be satisfied with the film,” notes Fessenden.

“We actually went back, a year to the day later, and re-set up the room and the clothing exactly as it had been before. If you watch that scene closely, you can see the quality of the film changes, because a year after we had filmed the first part of it, we actually knew how to use our camera. It’s much nicer photography when they move in for the kiss!”

Fessenden chuckles when I ask if both his male leads are gay. “The blond kid, David, is very straight, but he’s also very professional, and it was mostly his suggestion to put the kiss in. The other kid is bisexual — he’s out on our website so I guess I can say it — but because of that, he had a little more trouble with it, because it was a little bit more fraught for him. There was a bit more sexual tension there.”

Some straight audience members have had difficulty with that moment, too, says Fessenden. In Florida, “one kid, a teenager, ran out of the room. He did come back afterwards, about 10 minutes later, and finished the film, and seemed to enjoy the rest of it. But we asked him, ‘What happened? Why’dja take off?’ And he’s like, ‘It was too gay for me!’ At least he came back and finished the movie!”

Somewhat surprisingly, Fessenden himself has been accused of homophobia. As the plot thickens, David turns out to have much darker secrets than Jonathan initially suspects. “It’s not that David’s the villain because he’s gay,” Fessenden explains. “It’s just following a classic story arc. He’s sort of the equivalent of the femme fatale. I would compare him to Kim Novak in Vertigo, or Barbara Stanwyck’s character in Double Indemnity, who fools Fred MacMurray into believing she’s in love with him so he’ll kill her husband for her.

“As a gay man, Jonathan would be unlikely to fall for ‘feminine wiles,’ so the traditional, heterosexual femme fatale would fail utterly,” he continues. “In order for him to be snared in the trap, David must be an attractive male, who can convince Jonathan that there is a romance budding between them. And Jonathan is gay simply because I happen to be gay, and most of my stories feature gay lead characters.”

Fessenden concedes that femme fatales do have a misogynist element to them (“they reflect men’s fear of women taking advantage of them”), but adds that “if both characters are the same gender, and one is manipulating the other, I think that changes things, especially if the author/director is gay, as well. Then it’s no longer related to gender-based phobias.

“It could be based upon some kind of deep-seated self-loathing that the author has for his or her own sexuality,” he acknowledges, “but that isn’t necessarily the case. I’m quite happy being gay, and have been lucky enough to never have any issues with my friends, family or co-workers over it.”

Fessenden’s awareness of genre is one of the things that makes The Sacrifice a fascinating film experience, adding a third G to its target audience: movie geeks.

As Jonathan and David use occult lore and details remembered from horror movies to further their investigations — often, rather amusingly, giving them equal weight — it becomes obvious that the filmmaker has watched a lot of horror movies himself.

He lists films like Rosemary’s Baby, a “dreadful” Pamela Sue Martin film called Bay Coven, and Eye of the Demon as inspirations for The Sacrifice; all involve protagonists who discover their friends and neighbours are really Satanists.

“I also really love another Polanski film, The Ninth Gate. I wanted to get the feel of searching through ancient tomes and finding all this stuff, and I actually did not succeed on that level,” he confesses. “That’s something that I want to do more of in my next film, to get this feel of these really ancient books that have dark secrets in them.”

Fessenden explains that the occult books that do appear in the film are “an in-joke: the antique dealer in the film, Eli, says, ‘I have a few books upstairs’ and Jonathan walks up the stairs into the largest occult bookstore in Maine and New Hampshire, Weiser Antiquarian Books. There are thousands of books there, dating back to the 1800s, many of them original editions, and they can be very pricey.”

The Sacrifice has a few other small in-jokes to reward the savvy. When, at a crucial juncture, Jonathan calls on Anubis (the jackal-headed deity who “opens the way” in Egyptian lore) to show him the path, audience members who understand the reference will get a chuckle out of how his prayers are answered. Knowing who Set and Osiris are also opens a rich vein for interpretation of the film, and its sequel, The Resurrection, which Fessenden is currently shooting.

The Resurrection, Fessenden tells me, is “much more of a horror movie. There’s much more violence, much more blood — it’s much gorier!”

That doesn’t mean The Resurrection isn’t gay; it does overtly table the theme of homosexuality a couple of times, like when Jonathan comes out to his mother. “But that’s not the focus of the film, and it’s not a big deal,” says Fessenden.

“There is a character in the film who is much more sympathetic, who is starting to get a crush on Jonathan,” he notes, “but it is a horror film… and everyone dies horribly!”

I ask Fessenden if, given the very dark themes of both these films, he was consciously trying to navigate any of the fear surrounding homosexuality in our culture. While he concedes the films are dark, he says his intent is just to make good, scary movies that gay audiences can find themselves in.

“Right now, there’s a lot of this ‘we’re just harmless and funny, so don’t be afraid of us’ movies, and there’s also a lot of films dealing with the trauma of coming out. I think we need to get past that. I enjoy a lot of those films, but from my perspective where gay film needs to go next is good films that tell a good story and the characters just happen to be gay, and that is not the focus of the story. If my characters were straight, they probably would behave pretty much the same as they do in these films,” he concludes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra