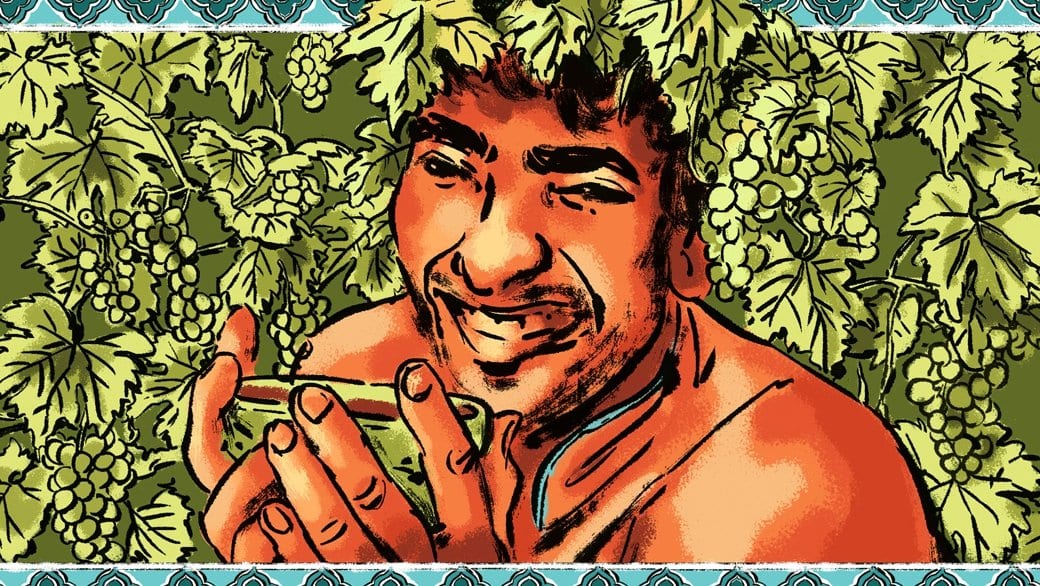

Poet and holy man Shah Hussain was the Punjabi-Islamic Dionysus of the 15th century, and a rebel in both his religious and love life.

The notorious poet was born in 1538 the cosmopolitan Punjab centre of Lahore, India, now on the eastern extremity of Pakistan (It was rebuilt in the 11th century by Malik Ayaz).

Hussain was the son of a weaver and Islamic convert at a time when Islamic rulers throughout the Punjabi region inspired lower-caste Hindus to convert; however, many of these converts became outcasts among Hindus and unable to move up, remaining as remained labourers and artisans.

As a child, Hussain attended the local mosque that doubled as a madrasa, a college of Islamic instruction, where students learned to recite the Quran from memory. Hussain’s studies eventually caught the attention of Sheikh Bahlol Dariai, a wandering Islamic scholar who had taken vows of poverty and austerity. Poet Naveed Alam translated Hussain’s poems in his book, in Verses of a Lowly Fakir. He says that the Sheikh, “broadened the parochial horizons of his young ward, daring Hussein to fathom the unconventional ways in which traditional texts could be interpreted.”

In 1574, while studying under another respected Islamic scholar, a 36-year-old Hussain was deeply inspired by Sura Al-Hadid 57:20 from the Quran: “Harken, Ye Folks, the world is a play and a show, a display of pageantry, pride, and boasting between yourselves, and competing with one another for greater wealth and number of children.” This quranic takedown of vanity and material wealth would resonate throughout the rest of Hussain’s life.

Hussain is also known for breaking out into a spontaneous dance and abandoning organized religion. Eventually his original master heard of the disgrace of his dancing pupil, who now led a pack of revelers through town, and returned to bring Hussain to his senses.

Hussain complied by leading a prayer, but upon reciting the verse, “Did we not open your heart, and ease your burden which weighed down your back, and exalted your fame?” (Sura Ash-Sharh 94:1-4) he burst out into laughter and ran away again. Alam writes, “In time, Hussein acquired quite a reputation: a rebel fakir dressed in all red, bearing a wine flask in one hand and an earthen bowl in another.”

His religious philosophy wasn’t the only way Shah Hussain lived an unconventional life. At some point he met a man named Madho Lal, and they became lifelong loves (which others say, lifelong friends). There’s very little biographical information about Madho Lal, or their relationship, save that he was a “Brahmin boy.” Was the relationship an intergenerational one? Pederastic as between a teacher and student? Were they more equals? “Brahmin” would suggest a Hindu teacher or priest of some kind, but the descriptor could simply refer to the fact that he was descended from working class, spiritually observant Hindu parents.

What is known is that Hussain loved Madho Lal so much he had his named officially changed to Madho Lal Hussain to signify their eternal unity. According to Manzur Ejaz, a Pakistani-American writer, Lal became the leader of Hussain’s followers after the free spirited poet-priest’s death at the age of 61.

A biography by Manzur Ejaz describes Shah Hussain as developing a following of more than a 100,000 devotees with 20 successors, but this did not inflate the irreverent holy man’s ego. Apparently, he disdained higher-ranking Islamic scholars, and if someone asked to be initiated by Hussain he would tell them to, “shave your head and drink an earthen cup of wine with me,” hence the Dionysian comparison.

Hussain also pioneered a genre of short Sufi-Punjabi poems called Kafis, which is made up of verses that are repeated at intervals throughout the poem, almost like a song. Hussain is considered by many as a pioneer of the Kafi form, and his are designed to be sung, with refrains and four to 10 lines.

The poems are beautiful, with small meditations on life, love, meaning and spirituality. Two freely available Kafis mention Madho Lal by name, one reflecting on the “unknown road” of the afterlife, another where the author is ostracized for drinking “the forbidden wine.”

A friend of mine from the region explained that during Hussain’s annual death anniversary called Mela Chiragan, or the “Festival of lights,” celebrants light candles and lamps, play drums, dance and smoke hashish. Hussain is regarded as a Sufi saint, and to this day, Hussain’s poetry-songs are still sung today, as our his praises for his non-conformity and valuable wisdom.

While Hussain made sure he and Madho Lal were symbolically unified in life, they would also not be parted in death. Even today, in Hussain’s tomb and saint shrine in the Baghbanpura district of Lahore, the two rest side by side.

History Boys appears on Daily Xtra on the first and third Tuesday of every month. You can also follow them on Facebook.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra