Heterosexuality reigns supreme in the legends of gallant knights. Romantic stories of the chivalric warrior, à la King Arthur, were first put down in the High Medieval period, around the 12th century onward. We have an image of virile, gallant young men courting many a swooning noblewoman — and it’s a total myth.

So let’s tell our own story about the life of a medieval knight named William. Born around 1147, William was the second son from a second marriage of John, the royal marshal — a protector of the King of England. As was the tradition for youth aspiring to knighthood, especially for sons who wouldn’t inherit their father’s land and had to seek their own fortunes, William was sent to the household of the Count of Tancarville in Normandy, France.

William, a strong, well-made young man, dark of hair, swarthy of skin, and described as having quite a sizable “enfourchure” — crotch — squired for his lord’s chamberlain, a high honour. After eight years of training he was knighted in 1167. As was tradition for knights of his time, William left Tancarville and, after protecting King Henry II’s wife from Spanish rebels in her homeland, came into the good graces of the English royalty. Henry II set up a maisnie (a “household”) for his 15-year-old son (who is of course also named Henry), and asked 25-year-old William to oversee the prince’s training.

William’s life was devoid of nubile young maidens. The world of knighthood was a man’s world, especially when it came to these non-inheriting sons. Noble, virgin daughters were the concerns of fathers who wanted to arrange decent marriages and pay their dowry.

There was also a lack of roaming bands of Christians condemning medieval sodomites to burn at the stake. The church was constantly scrambling for a foothold in medieval Europe, especially early on, and it took a very long time for their anti-sex teachings to take hold. William’s world was one inherited from Germanic tribal life, where the only major laws related to sex were about protecting the virginity of daughters. Homosexuality mostly didn’t factor into laws, and there was even a Germanic tradition of love between warriors and their initiates. This continued well into the High Medieval period — among many clerical testaments to knights’ overwhelming homosexuality, the clergy decried that knighthood was awash in “the vice of Sodom.”

William would go on to have an extraordinarily successful career as a landed knight in both England and France, and as a court diplomat and royal leader (he would eventually inherit his father’s position after the death of his older brother). He also had a number of great loves throughout his life, none of which were women. At 43, he did marry 17-year-old Isabel de Clare, as he’d promised the Pembroke Earldom, but his true loves were always men.

Chiefly amongst these was Henry the Younger, a deep and life-long love in the style of a great romance. At one point, jealous courtiers attempted to spread a rumour that William was sleeping with Henry’s wife. Henry, in anger, “withdrew his love from” William, and the knight left Henry’s court . . . but not before competing in a tournament as part of the prince’s household, winning numerous matches and saving the prince from defeat. At one point, William confronted Henry’s father, the king, in front of the royal court and challenged his accusers to confront him in trial by combat, even offering to cut off a finger as a handicap to make the fight fairer. No challenger would come forth, and the prince wouldn’t involve himself, so William left. But after two weeks, the prince had gotten rid of his wife and sent word to William, begging him to return.

William loved his squires as well, especially a teen named John D’Erley, described as his “bon amour.” Their relationship would last more than three decades, and D’Erley was at his lord’s bedside for the months leading up to his death. The story about this heroic knight, William the Marshal, doesn’t describe his nightly proclivities with men or women. What’s clear, as one historian explains, is “only men are said to love each other in a narrative from which women are almost entirely absent.” How’s that for a knight’s tale?

(History Boys appears on Daily Xtra on the first and third Tuesday of every month. You can also follow them on Facebook.)

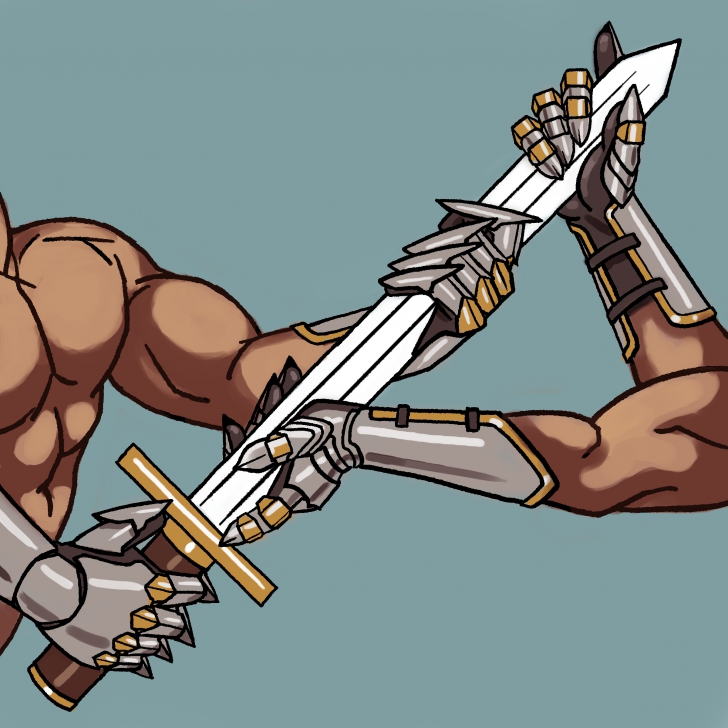

Original illustration by Yigi Chang.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra