Samuel L Jackson challenged his mortified interviewer, Jake Hamilton, to say nigger, but he just wouldn’t go there.

“Try it,” Jackson thundered last year after Django Unchained hit the screen, but Hamilton mustered only a meek refusal. So Jackson rightfully refused to discuss the sanitized in-law of “nigger” — the “N-word.”

I may have missed that Intro to Slavery and Colonialism elective, but I don’t recall hearing of plantation owners and whip-cracking overseers saying, “Hey, N-word,” as they herded, separated, whipped and otherwise abused African people.

Watching the squirming Hamilton and the gleeful Jackson was viscerally entertaining — and irritating. It reminded me of an exchange I had in 2009 when I attempted to retrieve my tickets for Berend McKenzie’s one-man show.

“Two tickets for Nigger Fag, please.”

“Easy for you to say,” the attendant shot back, after recomposing himself.

Yes and no. For one thing, calling the show “N-word, F-word” is a political-correctness bridge too far, and I had no intention of crossing it.

For another, nggrfg is meant to inspire discussion about words and people’s experiences with their power. Or, I should say, the power we give the words we use and how that perceived power continues to evolve.

After covering a white pride march in Vancouver a few years ago, I found a photo of myself labelled “Aunt Jemima” on the website of a white power activist. I couldn’t stop laughing. That was the best he could do, all these eons after that image was slapped on a pancake-syrup bottle?

And yet, I did feel the sting of insult because his intention was to hurt, denigrate and dismiss me. He would have that power only if I let his intention seep into my blood and rattle my sense of self, which he knew nothing about and didn’t care to know.

“There’s nothing wrong about language. It’s what people do with language that hurts and incites panic and fear and anger and resentment and hatred. It’s the people behind the language,” McKenzie once told me.

However inflammatory the words nigger and fag are, they are an intrinsic part of our heritage that still resonate with and affect us. Trying to make them innocuous by refusing to name and confront them makes them more sinister than they should be — and increases their power to injure and incapacitate.

Many of us call ourselves gay, but there are students walking school corridors who recoil when they hear the putdown “That’s so gay.” It won’t stop us from calling ourselves gay — at least, I hope not.

We have bent, shaped — reclaimed, if you prefer — the words we use to name our desires, declare our presence and describe who we are. Fag, queer, queen, bitch, slut, nigga, dyke, she-male, tranny — all have been slurs and, for many of us, still are, even as some of us embrace them.

You may decide all this “reclamation” is not up your alley. Nothing wrong with that. I’m not particularly fond of “nigga” or “Hey, nigga, what up?” and I don’t foresee adopting them. But others have, and I’m okay with that. It’s in their comfort zone, context, maybe even identity — like queer, and even fag, have become for others, who may eventually decide they don’t fit anymore.

We have queer film festivals, queer arts festivals, queer resource centres, the activist group Queer Nation and — wait for it — the contentious Queers Against Israeli Apartheid. We have slut walks, dyke marches, and I remember a pub that had Fag Fridays.

I get that we can be an incohesive, cantankerous community, passionate — often offensively dismissive — about our disagreements, but we have more urgent issues to tackle at home and internationally than getting bogged down, snippy and snarky over names and labels.

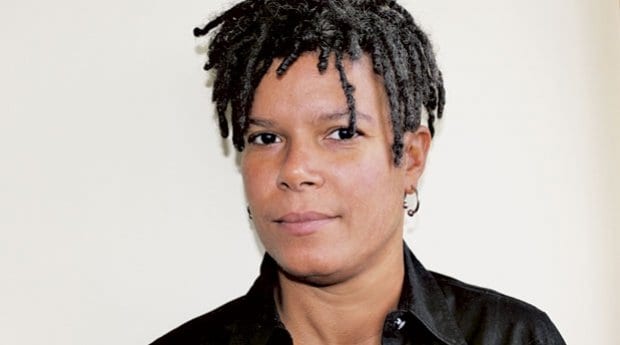

Natasha Barsotti is the staff reporter at Xtra Vancouver.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra