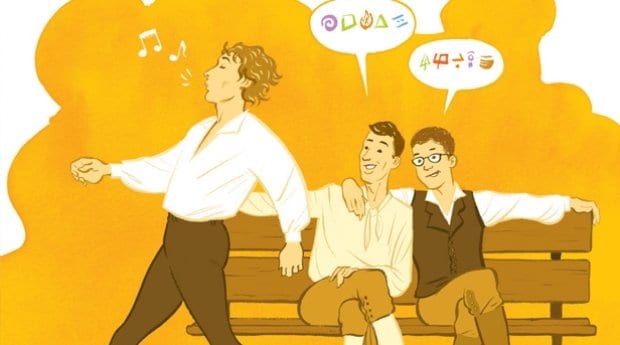

Picture this: you and me in a bar, a mixed crowd, mostly straight. I sidle up to you and shout over the din, “Bona nochy, my bijou bitch. Vada the dish on that dally gajo! Think he’d charver with this omi-palone, or is he naff … maybe bibi?”

Maybe you’d think I’m completely insane, or maybe you’re one of the few people in the room who understands. “Aunt Nell said he’s a dilly boy when the dinari’s bona,” you cackle, “but tonight he’s alamo, ogling you for a bold blag.” You and I have just parlayed in majestic Polari, the “linguistic mongrel” of thieves, travelling entertainers and homosexuals.

Polari — which can be traced back to at least the 19th century, possibly as early as the 16th — isn’t so much a language as an in-group lexicon; it’s a secret lingo that grew and evolved as it borrowed from a number of disparate groups and languages.

In her dissertation on the lost gay language, Heather Taylor explains that Polari likely grew out of cant slang: phrases or catchwords passed among travellers, vagabonds and criminals. Cant could be picked up quickly and was incomprehensible to outsiders, providing speakers a certain amount of secrecy. With its wide range of words for body parts, bodily functions and genitalia, cant was a true language of the demimonde.

Another likely influence is Mediterranean Lingua Franca, one of a number of bridge languages used to make communication possible between speakers of different tongues, which was cultivated by sailors and enriched with “nauticisms.” Injured or retired British sailors who had trouble adjusting to home life in the 18th and 19th centuries would join travelling groups and circuses, mixing Lingua Franca into the cant that was used within those groups.

An influx of Italian immigrants to England in the 1840s added to this growing lexicon, since they often worked as entertainers, too. Travelling actors and circus people were despised, even to the point of being denied Christian burials; they used a linguistic relative called Parlyaree. Influences from “gypsy” — a derogatory term for Romani people — lexicon added back slang (a coded language in which written words are pronounced backward — for instance, “boy” becomes “yob”) and rhyming slang. Other elements were borrowed from Yiddish, the Cockney dialect and Shelta, a cant of Irish travellers.

As gay scenes began consolidating in urban centres in the 19th and 20th centuries, police action against them grew, necessitating the insular community of which Polari was a key component. It reached its height as a secret gay language in London in the 1950s and 1960s, when police entrapment was routine. This was coupled with the rise of flamboyant “camp” culture, which the outrageous language is well suited to.

If the mid-20th-century’s state-sanctioned crusades necessitated a language that offered protection and secrecy from heterosexual culture, the rise of political and societal protections in the late 20th century was what killed Polari. After England decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, public opinion slowly started coming around for the omi-palones and palone-omis (mannish women, ie lesbians).

With gay pride on the rise alongside a zeitgeist of virile gay masculinity, Polari, camp behaviour and effeminacy — seen as irreverent and carnal symbols of prior repression — were denigrated and rejected. Only as it fell out of use within the gay community did Polari begin to be studied seriously and documented. Much was lost, as tracking the mostly spoken language proved difficult.

I didn’t even learn about Polari until late 2013, but I owe my newfound knowledge to the Polari Rosetta Stone program compiled by Damien Atkins for the Buddies in Bad Times production of The Gay Heritage Project. Atkins’s spoof reintroduced Polari to many gays who might have gone their whole lives without hearing nary a “cod cottage” or a “zhooshy shush bag.”

History Boys appears in every issue of Xtra.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra