“She wanted to play Mame on Broadway so badly she could taste it,” Lorna Luft famously said about her mom, Judy Garland. It’s a shame that it never happened, because the classic 1966 musical of the same name has it all: a brassy but vulnerable leading lady, a colourful milieu, glamorous costumes and a high-kicking ensemble. It’s also stuffed to the gills with brilliant songs. Jerry Herman’s score swings, croons, belts and struts for miles, giving its star every opportunity to endear herself to the audience.

In many ways, Mame is the prototypical Herman musical — and from Hello, Dolly! to Mack & Mabel to seminal gay favourite La Cage aux Folles, his formula hasn’t changed: plant a fabulous lady of a certain vintage centre stage and let the audience do the rest. But is there more to making a classic? What is it that gives certain musicals a legendary status while others flop? A fabulous lady of a certain vintage who is used to being planted centre stage has an answer.

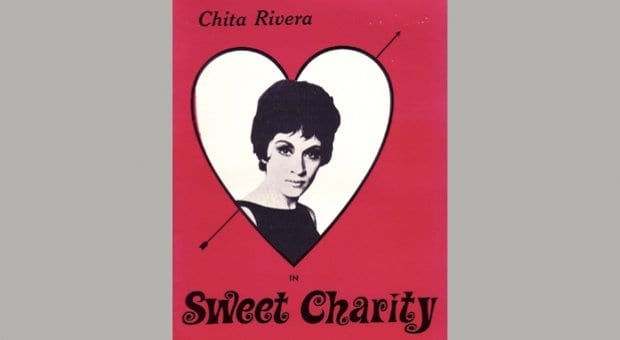

Chita Rivera is a beloved Broadway star with a long list of both hits and flops under her belt. Toronto audiences might remember her best from her Tony-winning turn in Kiss of the Spider Woman, climbing around a massive spider web and slinking through the show in a series of ever-more-spectacular costumes and tangos with her Canadian co-stars (Brent Carver, Jeff Hyslop and Juan Chioran, respectively).

I was 12 when Rivera came into my life, and one of the first things she taught me was that a good musical must wear its humanity on its sleeve. I remember her barking, “You’re wearing the wrong shirt!” when I showed up in a Cats T-shirt. Never one to mince words, she then told me her opinion of the show; needless to say, she wasn’t a fan.

The era of the mega-musical (Phantom of the Opera, Miss Saigon, Les Misérables) was then still in full swing, but now she says, “I’m from the golden age, when every theatre had a hit in it. Helicopters and falling chandeliers are great, but not as great as the human body.” She’s definitely someone who would know, with classics like Chicago, West Side Story (“Imagine being a young Puerto Rican girl from Washington, DC… and she finds herself in a New York City rehearsal hall watching Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents and Jerome Robbins create a masterpiece!”), Sweet Charity (directed both onstage and onscreen by Bob Fosse, thank you very much) and Bye Bye Birdie on her resumé. In every case she credits the human element of those shows as an important aspect of what made them great.

Bye Bye Birdie was revived on Broadway a few years ago, but the new technology used in the show didn’t sit well with Rivera. “The people who try and change Birdie tend to mess it up. It’s anchored in a particular time and place.”

The director of the original production, Gower Champion, would go on to direct and choreograph such smash hits as 42nd Street and Hello, Dolly!, but in 1960 he staged an ending for Birdie that was uniquely human and personal for the time, an ending that helped the show earn its place in the history books. “In my opinion, the original ending that Gower gave it is inspired. The musical theatre that I came from always ended the same way: after all these big numbers, the whole cast comes downstage and sings whatever was supposed to be the show’s hit song in this big, overblown fashion. What Gower did to end Birdie was to have two people, Albert and Rose, singing this very simple, very sweet song called ‘Rosie’ and just walking into the sunset. It couldn’t have been more effective or more beautiful.”

For better or for worse, musical theatre has evolved from the vision that directors like Fosse and Champion envisioned. Roles aren’t even called roles anymore; they’re called “tracks,” a clinical and dehumanizing term that implies robotic precision and a total lack of individuality.

In order to be successful, a musical can’t just be a classic anymore; it must become a theme park. Oscar-winning composer and lyricist Stephen Schwartz gave us Wicked in 2003. It’s a wickedly popular show, but for seemingly all the wrong reasons. We want to see Elphaba go up in the cherry picker and Glinda enter in her bubble so badly that we ignore the uninspired choreography and all but the two or three most popular songs. There’s no getting around the fact that much of his score is, to put it mildly, not great.

Writing about Wicked’s 10th anniversary on Broadway, Kevin Fallon said in The Daily Beast, “As anyone who’s seen the show once knows, the minute that teacher starts bleating and turning into a goat while singing, it’s time for a bathroom break.” While there are many ways to play a character like Chicago’s Velma Kelly or Gypsy’s Madame Rose, the characters in Wicked seem part of a prepackaged offering. It’s musical theatre by way of frozen TV dinners, indicating to me that it’s the total experience of Wicked people cherish, not the craft of creating theatre.

Is there a happy medium? Andrew Lloyd Webber thought so in 1995. The man who ushered in the era of mega-musicals brought us Sunset Boulevard, his version of the 1950 movie about Hollywood, greed, vanity and delusion.

We can all identify on some level with the central characters of Norma Desmond, who sees her youth slipping away and can’t let go of yesterday, her boy-toy Joe Gillis, who takes what seems like a good opportunity but gets in over his head, or Betty Schaefer, the naive innocent girl who just wants to be happy. The human elements of Sunset Boulevard were in place, but don’t forget, this was a Webber show. Instead of focusing on relationships, he gave us onstage pools! Hollywood film sets! A gargantuan flying house! Glenn Close, Betty Buckley, Diahann Carroll and Elaine Paige all headlined the show at some point, but in every one of their reviews, the set changes seemed to get top billing.

Of all the artists mentioned in this article, none have been only successful or only failures. Herman had flops like Dear World, and Schwartz wrote wonderful scores for Pippin and Godspell. Webber crashed and burned hard with his Phantom of the Opera sequel, Love Never Dies; you’d think he would have learned from Rivera’s Birdie sequel, Bring Back Birdie, which ran for four performances on Broadway in 1981. In her deadpan words, “He just didn’t wanna come back.”

Ultimately, musical theatre is two things: a) an insane gamble and b) an impossibly unique art form. More immediate than cinema, more ephemeral than literature, more emotional than ballet and more fluid than music, musical theatre is what happens when it’s no longer possible to express a feeling in words; it must be danced, sung and acted, full out. It’s storytelling to the nth degree. It’s bodies and voices. It’s blood, sweat and tears mixed up with sequins, greasepaint and feathers. I’m in total agreement with Rivera on this: whether the show runs for years or for less than a week, musical theatre is at its best when it’s wonderfully, artfully human.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra