Poster from the 1912 Olympic Games. Credit: Xtra file photo

Figure skater John Curry was the first openly gay athlete to win Olympic gold. Credit: Xtra file photo

Poster from the 1952 Olympic Games. Credit: Xtra file photo

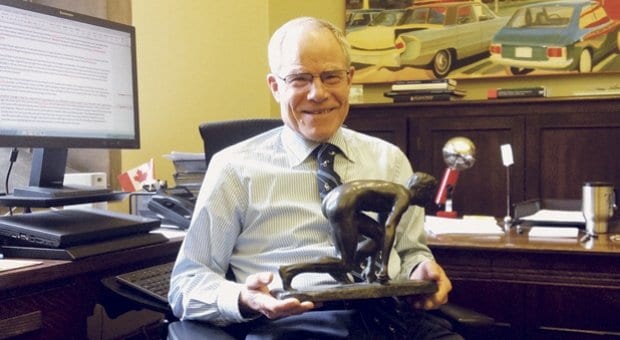

Professor Bruce Kidd, of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, says sex has always been a part of the Olympic Games. Credit: JP Larocque

There is no room in competitive sport for homosexuals.

That was the basic message of Russian legislator Vitaly Milonov in an interview earlier this year. Ardent in his support of his country’s anti-gay laws, he dismissed the International Olympic Committee’s assurances that international athletes and tourists would be exempt from arrest. “The federal law is valid throughout the territory of the Russian Federation and no one has the right to suspend it,” he stated. Meanwhile, Russian athletes were “traditional, normal people with big families,” whereas gay and lesbian athletes were framed as inherently weak because of their sexual preferences.

“I just think that if an athlete is normal … everything is normal. And if [they are gay], there should be some excuse they come up with — “I’m not running because I’m not a man or a woman.”

Milonov’s comments provide fascinating insight into the way in which Russian lawmakers have shaped the conversation on sexuality and gender in their country. Perhaps most interesting, however, is how his statements about sexuality and athleticism reveal an utter lack of awareness about the origins and traditions of the Olympic Games — namely, that from their very inception, the Games have always maintained a strong link to same-sex desire.

“Eroticism and sexuality have always been part of athletics, sport and other forms of physical activity, even though some institutions have sought to channel the discipline and exhaustion of sport and physical activity into sexual abstinence,” says Professor Bruce Kidd, of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education. “In the ancient world, homosexuality was closely associated with athletics and celebrated as such in poetry, sculpture, vase painting and other representations. The ancient Olympics began as an integral part of the system of power by which male aristocrats garnered a disproportional share of the social surplus for themselves. The cult of homoeroticism was closely bound up with that system of power.”

Between 776 BCE to roughly 260 CE, the Games were considered to be the most prestigious event in ancient Greece. Every four years, the sacred site of Olympia was flooded with spectators from the surrounding regions for an event that was a combination of both religious ceremony and pure voyeuristic spectacle. And key to that spectacle was the celebration of the male body, considered to be the physical embodiment of the perfection of the Greek gods.

Aristocrats and labourers were brought together under a strict exercise regimen and stripped of their garments. Foot races, discus throwing, boxing and wrestling were just a few of the sports performed in the nude, and while women did participate in the games as athletes and trainers, their competitions were kept separate and were less popular. In fact, many of the surviving depictions of female athletes often have them clothed — suggesting both propriety and an intentional separation from erotic display.

While many historians are reluctant to classify the ancient Games as gay in the modern sense of identity and sexual orientation, they do acknowledge that the athletic competition was a reflection of the prevailing attitudes of the time. And in Greek culture, pederasty was common between men of the aristocracy and prepubescent boys. Far more than a mere sex act, this union was seen as a mentorship that had as much to do with an exchange of knowledge as sexual desire and that often ended at the onset of adulthood, when the young men would settle down with female partners and start families.

“Champions were rewarded with lavish cash bonuses, lifetime pensions and generous gifts of merchandise,” Kidd says. “Not infrequently, their victories opened up the doors to successful careers in politics and business.”

And, in certain cases, victorious athletes would become objects of sexual desire, profiting from their newfound fame by becoming lovers to the wealthy.

The ancient Games remained a popular draw until 393 CE, when Christian emperor Theodosius banned all pagan festivals. Aside from a few regional athletic competitions in the centuries that followed, the Games remained mostly dormant until French educator Pierre de Coubertin launched a version of the Games in 1894 that would foreground more modern concepts, such as fair play, bureaucracy and an overall adherence to rules.

And in many ways, these modern Games were also a reflection of the predominant cultural anxieties of the time — namely, that men were becoming too feminized as a result of modernity and the Industrial Revolution. With farming communities broken up and fathers separated from their sons, many feared that a lack of male influence in homes and in schools would lead to a “softening” of Western males. Organized sports were viewed as a means to reestablish the gender binary by separating men and women and reinforcing masculine values.

Still, even with this newfound focus on shoring up masculinity, homoeroticism at the Games has continued to prevail in both overt and covert ways.

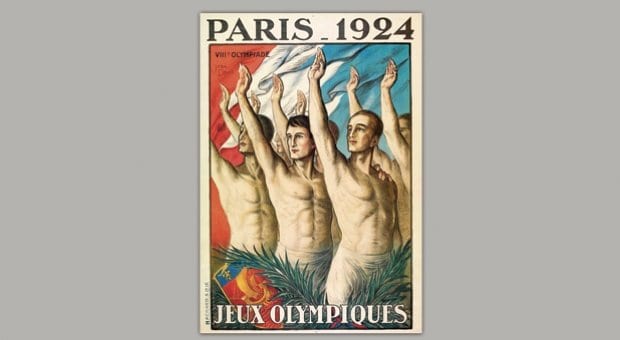

“Virtually every [modern] Games has produced powerful homoerotic images, especially the official posters from Stockholm 1912 through to Helsinki in 1952,” Kidd argues. “And of course, sex has always been part of every Games, which is why condoms are now distributed to the athletes in every Village and quickly run out.”

Prior to 1960, historical examples of homosexual Olympians are limited at best, and the stories that do exist are often tragic. Because of the laws in place during much of the 20th century, few athletes were able to be open about their sexuality, and those who did come out often faced harsh punishments or had the truth buried by family and friends.

But with the gay rights movement blossoming in the 1960s, more athletes began to feel comfortable about going public. In 1976, English figure skater John Curry became the first openly gay athlete to win Olympic gold. And in 1982, Tom Waddell, a participant in the 1968 Olympic decathlon, founded the first Gay Games in San Francisco.

Over the last 30 years, the number of openly gay athletes has steadily increased. Greg Louganis, David Pichler, Patrick Jeffrey, Mark Tewksbury and Anastasia Bucsis are just a few of the Olympic competitors who have acknowledged their sexuality in the interest of making positive changes to the system. And yet even with gradual progress, gay and lesbian athletes continue to have a hard time finding support — both within the world of sports and even within their own families.

“I think being a national or international athlete would certainly add to the difficulties of coming out,” says Marko Gadzic, who participated in both the Outgames and the Gay Games. “However, I never worried too much about letting people know I was gay after I came out. It was all the people I felt like I was going to disappoint by coming out — mainly family and friends.”

Athlete Raymond Reid agrees but also feels that the pressure to conform extends well beyond the personal sphere. “In terms of athletes remaining in the closet, it’s definitely a cultural thing in whatever sport,” he says. “I’m not just talking about the locker-room mentality, but even at the professional levels, it’s a marketability thing — similar to actors who are afraid to take the risk.”

And it was this fear of risk that motivated WinterPride CEO Dean Nelson to seek out and create a safe space for gay athletes. Using national pavilions in Olympic Villages as a model, he founded the first Pride House at the Vancouver 2010 Games, which was a huge turning point for many queer Olympians.

“The culture prior to and leading up to 2010 was still very much hostile towards LGBT, and I suspect it was in Montreal [at the World Outgames] that the seed was planted for the Pride House concept,” he says. “It was my first experience interacting with LGBT sports, and I realized that some of these athletes … could be Olympic hopefuls or Olympians, as in [Tewksbury’s] case.”

The first Pride House was an unprecedented success. Over the course of the competition, 20,000 people visited the three Pride venues, and the pavilion was one of the top international news stories to come out of the Games. In 2012, a similar project was launched at the London Games.

Professor Kidd sees the institution of Pride Houses as an important strategy to affirm and protect the community. “One of the moving untold stories about the Pride Houses in Vancouver is the number of athletes, coaches and officials who were given refugee status by the Canadian government.

“As long as there is so much persecution … in many parts of the world, Pride Houses that affirm LGBTIQ among the sports community and the greater public and enable such refugee status are essential.”

Which, of course, brings the conversation back to Sochi.

With the massive success of the Pride House concept, queer sports organizations like the Gay and Lesbian International Sport Association, the Federation of Gay Games and InterPride had expressed an interest in creating support and continuity between international host cities and major athletic events. These conversations laid the groundwork for Pride House International, a coalition of community groups and leaders that was founded in the wake of the Russian government’s rejection of an application to create a Pride House at the Sochi Games.

Nelson and WinterPride are a part of the coalition, and they are working closely with Konstantin Yablotskiy and the Russian LGBT Sports Federation to help protect queer athletes and spectators in Russia during the 2014 Games. “We are lobbying the IOC to update their charter to include sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression in Article 6 of the Olympic Charter, where it states sports must be free of discrimination of any sort,” he says.

Pride House International is also applying pressure on the IOC to update its selection process to ensure that future host destinations embrace full equal human rights in order to avoid a situation like Sochi happening again. Or, as Nelson puts it, “if a destination wants to host the Olympics and sees the value in bringing the Olympic spirit to their nation, they will need to modify their laws to ensure [they are] in line with the Olympic Charter.”

In the event that the group is ultimately unsuccessful in getting a Pride House off the ground in Sochi, the coalition is looking into the possibility of a virtual Pride House, as well as creating additional houses in other countries around the world and spearheading a same-sex hand-holding initiative that would encourage those who attend the Games to hold hands with other people of the same sex.

“Keeping up a friendly dialogue with the IOC and other sporting bodies is important. We will collectively continue to lobby, at a local, national and international level, the Olympics and other major sporting bodies to ensure a safe and inclusive space for all athletes is possible.”

Meanwhile, the Russian LGBT Sports Federation has been organizing a gay-friendly athletic event to be held in their country following the Winter Olympics. Dubbed the Open Games, the competition welcomes athletes of all orientations and will take a more indirect approach to promoting tolerance by placing emphasis on athletics rather than on human rights or politics.

“Sport is a universal instrument to solve many different problems,” Yablotskiy recently told The New York Times. “By developing LGBT sport, we can improve the standing of the LGBT community in our country. Our society has a very one-sided image of gays. People don’t understand that anyone could be gay. Your boss could be gay; any good, normal person could be gay.”

In contrast to a less direct approach, Kidd sees value in visibility as an extension of personal identity. “I think the campaign within the Olympic movement should focus on … individual self-identification as the basic human right.

“Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter may prohibit political demonstrations, [but] wearing a rainbow triangle or carrying a small rainbow flag should not be taken as a ‘political demonstration,’ but simply a statement of self-identification … not unlike the act of waving an eagle feather or wearing a crucifix, turban, Métis scarf or hijab — all of which have happened at previous Olympics without incident.”

Gadzic is reluctant when it comes to demonstrating on foreign soil. “I would love to compete in Sochi, [but if I did] I would comply with the laws of the land. We can’t expect a country to openly be accepting of gays overnight.”

But Reid disagrees. “Laws like this … are a reminder that politicians aren’t above sacrificing human rights for political gain. The Russian government doesn’t own the Olympic movement, so I think it would be within the Olympic spirit to still compete.”

He pauses. “Doing so openly would be a tremendous benefit in terms of upholding the humanity of the Olympic spirit and fighting homophobia.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra