Allison Rennie says the sincere discussions among committee members shattered stereotypes and helped everyone gain a better understanding of each other’s views. Credit: Shimon Karmel

Don Collett initially sympathized with the members of the church who opposed gay ordination, but his views shifted. His wife left him for it. Credit: Shimon Karmel

Marion Best agreed to chair the committee on the condition that it would include a gay man and a lesbian as non-voting resource people who would be present for most of the discussions. Credit: Shimon Karmel

Six months before the United Church of Canada decided to ordain gay ministers in 1988, Tim Stevenson thought the contentious initiative was doomed to fail.

“We got up onstage, the report was given, and people were blown away,” says Stevenson, who hailed as a miracle the 388 commissioners’ decision to accept the report, called “Toward a Christian Understanding of Sexual Orientations, Lifestyles, and Ministry.”

“In the whole place you could see people saying, ‘Holy shit.’”

The report presented 25 years ago to the 32nd General Council, the national governing body of the United Church, stated that “all persons regardless of their sexual ordination who profess faith in Jesus Christ and obedience to Him, are welcome to be or become full members of the church.” It continued, “All members of the church are eligible to be considered for ordered ministry.”

With that vote, the United Church of Canada became the first, and only, mainstream Christian church in Canada to affirm that openly gay and lesbian people are eligible for ordination.

“To those who have been estranged,” Stevenson said in a subsequent speech to the council, “it’s time to come home.”

The report had been released six months prior to the General Council in order to give the 849,401 church members and 4,112 congregations throughout Canada and Bermuda time to properly consider it.

Congregations and a few presbyteries and regional conferences sent 1,800 petitions prior to council; most of the petitions adamantly opposed the report’s recommendation.

Stevenson, a graduate of the Vancouver School of Theology, was a resource person to Sessional Committee 8, which met prior to the council to consider the report and its petitions. After six days of discussion, debate and soul searching, all 24 members of the committee agreed to recommend the report.

“We wanted every single [committee member] to go up onstage and have seats up there so that all of the people in the auditorium could see that it wasn’t a two-thirds’ vote or some question of some members being on the fence,” Stevenson says. “People could see that this committee, which was made up of people of different theological perspectives from every part of the country, completely agreed. This included some members who came to vote no. It was amazing.”

Marion Best chaired the committee and later became church moderator. Going into the committee meetings, only two members supported the report, she recalls. Five were opposed. “The rest of the group were open to listening to one another with open minds before making any declarations about where they stood,” she says.

“It was really to come to terms with the fact that the church had not been supportive of gay and lesbian people and that it had resulted in most people being closeted who were part of the church,” she says. “It was a confession by the church that we had not been acting in any kind of Christian way with our brothers and sisters.”

Best agreed to chair the committee on the condition that it would include a gay man and a lesbian as non-voting resource people who would be present for most of the discussions.

“It came out of an ethical course at theological school where you don’t make decisions about aboriginal people, for example, without aboriginal people in the room,” she says. “So, I figured it was important not to make decisions about gay and lesbian people in the church without gay and lesbian people in the church present in the room.”

She picked Stevenson, who had already been elected as a commissioner to the General Council, as well as a lesbian named Allison Rennie, who had been actively involved in Affirm, a gay and lesbian group within the United Church.

Stevenson describes the committee meetings as the most intense period of his life.

“I mean, it was like nothing I’ve ever experienced,” he recalls. “I had to be ‘on’ all the time because people would raise this question, that question, and the stakes were so high. I couldn’t make mistakes. I had to be able to get people to understand. To turn people who were absolutely opposed. People who were sitting there with these 2,000 petitions and a Bible sitting on top. Their stance was ‘We have 2,000 petitions and the Bible says no,’ and that’s where they are starting from. I realized that in order to build consensus, these people have to turn around. I have got to get these people on our side.”

A turning point came on the second morning of deliberations when members filed into the classroom where they met and discovered homophobic obscenities had been written on the blackboard.

“Someone went to rub them off, and I said, ‘Leave them here, and we will leave them until we have had our worship,’” Best says. After a moment of silence, she quoted 1 Corinthians 12, which reads, “when one part of the body suffers we all suffer.”

“We never knew who wrote that,” Best says. “The room was kept locked because we kept our materials in there. That was our second morning together. That really hit people hard.”

“People started to care about each other, and over the period of a week I saw people really turn around,” Stevenson says. “People like the Community of Concern folks put these petitions aside. They literally pushed them aside one by one until every single person at the end of the week said ‘yes.’ We had complete consensus by the end of the week.”

The Community of Concern, comprising church members opposed to the recommendation, declared that they were “convinced that the biblical intention for sexual behaviour is loving fidelity for life within marriage and loving celibacy outside marriage.”

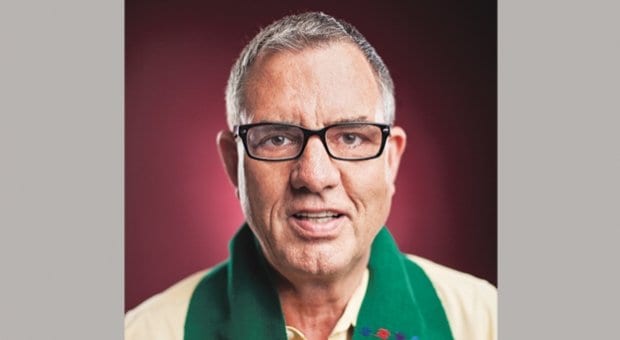

Don Collett, who sat on the sessional committee, sympathized with the Community of Concern’s views. He was also mindful of the many members of his church in Taber, Alberta, who had made it very clear that they did not want him to assent to the report.

“I think what transformed over the period at that council was a realization that baptism is what gives us membership in a church; it’s not how we behave or what we do,” he says. “It’s baptism itself. It’s not so much about if gays and lesbians are ordainable. It’s not; we’re all ordainable by virtue of our baptism and deciding whether people are of good character in the process leading up to ordination.”

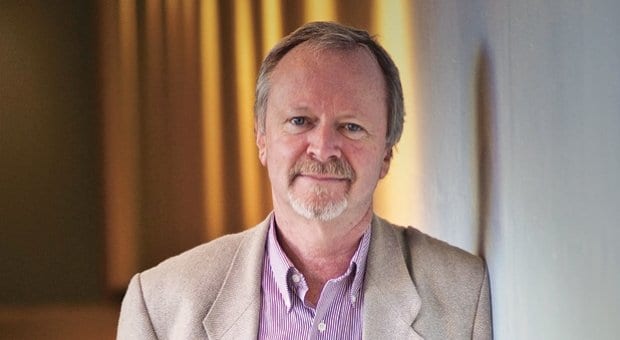

Rennie says members were moved by each other’s integrity as well as the Holy Spirit.

“People were willing to tell the truth as they understood it, and the other people really listened,” she says.

During the week of deliberations, Best had the committee members participate in a listening exercise in which they each explained why they held a particular position in five minutes of uninterrupted speech. During one such exercise, Rennie was grouped with a man whom she says was aligned with the most conservative members of the Community of Concern.

“We were talking more about marriage, going back and forth with me asking questions, and he was saying things that were outrageous to me, and offensive, but he was expressing his code, I guess, really strongly. And then at a certain point I said, ‘So, if gay people could get married, then it would be okay? That’s what you’re saying?’ And he said, ‘Yes, of course, then it’d be okay ’cause they’d be married, but they will never be able to get married, so it’ll never happen.’”

Rennie says that her stereotypes were suddenly “smashed all over the place” as a result of that interaction.

“I thought he was really anti-sexuality and at a certain level probably terrified and fearful of it,” she says. “But really, he just wanted an institution like marriage so gay sexuality could be faithful. So then we started talking about faithfulness in committed relationships, and then we found all kinds of common ground — that was his thing. That example had a huge impact on me because I could see how my own stereotypes of this conservative man kept me from hearing what he was trying to talk about. His stereotypes of what he thought I was saying kept him from hearing what I had to say.”

Stevenson says the week gave him a new understanding of the word “conversion.”

“You hear in religious terms about people converting; that’s exactly what these people did,” he says. “They went through a total conversion themselves and came to believe they were being called by the Spirit to move away and move to ‘yes.’”

Stevenson had been making the case for gay ordination within church circles for nearly a decade at that point. After finishing his studies in theology in 1980 he approached his home congregation, St David’s United in West Vancouver, and asked them to sponsor him for ordination.

“They took a year and said no,” he says. “They said that it was too difficult and they didn’t want to take it on. ‘It’s not a justice issue,’ they said. So I left there, and the people at First United Church who knew me said, ‘Why don’t you come to First United?’ So I joined their congregation, got to know them, got on the board, and it took a year and finally they said yes. They were the first church in Canada to support ordination.”

John Cashore, who was then minister at First United, did not view Stevenson’s sexual orientation as an obstacle to ministry. “The people at First United knew him well and came to the conclusion that this guy would make a great minister, and that was the issue,” recalls Cashore, who later went on to serve as an NDP MLA and cabinet minister.

First United’s decision was upheld by the next two levels of church governance, including Vancouver-Burrard Presbytery, which includes congregations in and around Vancouver, and the BC Conference, made up of presbyteries throughout the province.

“The fight then started at the conference level,” Stevenson says. “The people who were opposed could see the tide was turning in the conference and they were going to lose this one, and that’s when they swung and said, ‘The national must make a decision.’

“Normally, the national church never gets involved in ordination issues. People are ordained at the conference level. They are the ones who say you can become a minister. And normally, they are autonomous there, and they don’t want the national church interfering in their business,” he explains. “But the conservatives pushed this so hard, and they thought across the country they could get enough opposition to stop it.”

The chain of events that led to the 1988 decision began in 1981 when a lesbian named Susan Mabey disclosed her sexual orientation during the ordination interview process in the Hamilton Conference of the United Church.

“She went to her interview with ordination, completed all of her theological training, and at the last stage, where they need to approve her for ordination, she told them she was in a committed relationship with another woman,” Best says. “They said, ‘Uh oh, we don’t know if we can.’”

The conference sought a ruling from the national church, and at the 1982 General Council a committee was struck that would look into the question of gays and lesbians in the church. That committee’s report, co-authored by Marilyn Harrison and Robert Stobie, was presented at the 1984 General Council.

“We gave the church five different options and recommended they do ordain them,” Harrison says. “When it came to General Council, they voted that there was enough opposition to it that maybe the general church needed time to study the report more thoroughly, and another committee was established to study that report and present it in 1988.”

According to the annual statistics compiled by the United Church of Canada, 25 congregations disbanded and 25,000 people — about three percent of its overall membership — left the church as a result of the 1988 decision.

Collett’s vote for gay ordination, and subsequent refusal to retract that position, meant the end of his marriage.

“My wife left me,” he says. “She just felt that I had betrayed the cause. She had a bad experience in her early life around the issue and felt very strongly about it, so I knew it would be hard for her, but I didn’t know it would be the end of the relationship.”

He still stands by his vote. Though the United Church paid a high price in terms of member exits, he says, its decision paved the way for gay rights such as marriage. “Who would have predicted that 25 years ago? The United Church’s prophetic stand on this, at a cost to itself, led the way.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra