It’s the chokeholds that really stick in Jessie MacGregor’s memory-that, and the soft strip searches.

Nearly 40 years later, the trans man-who identified as a “baby butch” lesbian in the 1960s-still can’t forget the way Vancouver police officers raided the gay-frequented bars of his youth and harassed the queers inside. And now MacGregor wants an apology.

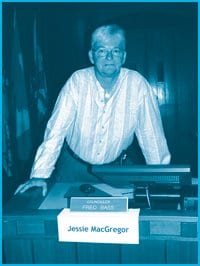

“I’ve been waiting since 1965 to be apologized [to] by the Vancouver police for their violation to the community and to myself,” he told a packed gallery at city hall’s Stonewall commemoration, Jun 25.

It was a particularly vicious period in police harassment history, MacGregor later tells Xtra West. “Law enforcement was used as a tool by the state to penalize me for my choice of sexuality.”

Those were the days when MacGregor hung out at The Montreal Club, which used to be located on East Hastings St, just below Main St. It wasn’t an exclusively gay bar, he notes, because that’s not the way it worked in those days. It was just a bar in a tough neighbourhood that tolerated “an odd assortment” of non-conformists, including street people, sex workers, and gays and lesbians.

An average night at the club would see people just doing their thing, MacGregor recalls-lesbians dancing in butch/femme couples, people drinking “booze out of brown paper bags” (since the club wasn’t licensed), a few people doing drugs, the occasional fight.

“I was underage,” he admits. “So I was always aware of that-but very determined to be in that place because my people were there.”

Suddenly the club’s owners would flash the lights. It was a warning, MacGregor recalls; it meant the cops were coming. “But inevitably they’d come anyway.”

And once they arrived, they’d harass the queers. They knew it was a gay bar, MacGregor says. They knew everyone by name. They put people in chokeholds, he continues, and checked people for drugs and alcohol. But they never arrested anyone during those raids. “So to me it just smacked of constant harassment.”

Though MacGregor never got caught for being underage, he still remembers the chokeholds. “It scared me,” he says now.

Then there were the clothing checks.

Vancouver, like many other cities in North America at the time, had a law saying women must wear at least three articles of women’s clothing at all times, MacGregor explains. And the cops enforced it.

“I think it was a way to harass [lesbians] legally,” MacGregor says.

He still remembers being “felt up” and then ordered to undo his jeans so the mostly male officers could check if the then-16-year-old baby butch was wearing women’s underwear-or not. This happened at least once a week for years, MacGregor recalls.

“I think I thought it was normal,” he continues. “I was in a world where these were the things I just had to put up with. Because I wanted to be with my people.”

Now, looking back at the way police treated him, MacGregor is angry. “It disgusts me,” he says. “I see it as a kind of soft rape.”

It was police harassment, he continues. “I don’t know of any other segment of society that was discriminated against in such a way over such a persistent length of time. We wouldn’t tolerate that today. We’d be down to see a lawyer right now. We’d be filing charges against the cops.”

macGregor’s story is not unique. Documentary filmmaker Aerlyn Weissman says she interviewed people “right across Canada” when she was researching Forbidden Love: The unashamed stories of lesbian lives. And she heard the same stories again and again.

“Queers were outside what was socially and politically acceptable,” she explains. “So the police felt quite free to harass, intimidate, mistreat guys that were obviously gay or butch women.

“They would never be called to account for treating people like that,” Weissman continues. “They had complete impunity. And you better believe there were cops who took full advantage.”

MacGregor says it’s time the Vancouver Police Department offered him and “every other little baby dyke and lesbian” an apology for the way its officers behaved in those days.

“We were regular folks just trying to find community,” MacGregor says. “We didn’t deserve that.”

Though he’s doubtful he’ll get it, MacGregor is hoping for an official apology on police letterhead. “I’d like a written apology on police stationary that says, ‘Collectively, we policed badly in those days and we don’t do that anymore.'”

A spokesperson for the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) says she can’t offer any apologies until MacGregor files an official complaint and gives her a chance to study it.

“If [MacGregor] feels slighted by the past, I’m sorry,” says Const Sarah Bloor, but she can’t comment without more information about the officers’ alleged actions-and she won’t engage in a “public debate.”

That was a long time ago, Bloor points out, adding that the VPD has a “very different relationship” with the gay community now.

It’s “unfortunate” that MacGregor is “perhaps living in the past,” Bloor adds.

MacGregor is furious. If he were a First Nations person seeking a government apology for being forced into residential school, would Bloor just say he was living in the past then, too? he asks.

Though MacGregor, who now lives in Kamloops, doesn’t think he wants to go through with the process of filing an official police complaint, he says the past is nonetheless still relevant. “The past is what shapes us, what shapes the future,” he says.

Weissman concurs. “We’re pointing at something systemic,” she says. Police have to acknowledge their “past bigotry and discrimination at a systemic level.

“I think somebody who was personally affronted or assaulted in the past should receive an apology,” she continues. “Not just an apology but a promise that these things won’t be repeated. That’s a dialogue that’s really appropriate.”

Lesbian city councillor Ellen Woodsworth couldn’t agree more. She says she still feels “very emotional” when she talks about those days. She, too, frequented Vancouver’s gay bars in the 1960s (though she preferred the Vanport). She, too, lived with the constant “terrible fear” of police raids and arrests.

“Even today, those of us who are older, we’re not as open, we don’t feel safe to lead our lives,” she says.

“We still live with the fear.”

That’s why she thinks a police apology would send an important message to the community. “I think it would be wonderful if the police would consider a statement from [MacGregor] or anybody else in the community and acknowledge what happened,” Woodsworth says. “It would be a strong message and an important step towards the healing that needs to take place.

“It would be an indication that the police department is really honouring all the work they’ve tried to do with the community these last few years,” she adds.

Gay city councillor and United Church minister Tim Stevenson also supports the call for an apology. “On face value, I would say yes, I think an apology is warranted,” he says. “You have to take responsibility for the past.”

It’s like the United Church, he continues. In 1988, the church offered the First Nations a formal apology for its role in the residential school system. Apologies help start the healing process, Stevenson says.

Though he understands why the VPD needs an official complaint to investigate before it can issue an apology, he says he hopes the force will look into MacGregor’s experiences.

“If, indeed, this complaint turned out to be upheld, I would certainly sit down with the Chief and talk to him and tell him why it would be helpful and healing [to offer an apology],” Stevenson promises.

“Not only for [MacGregor] but for other individuals who no doubt had difficulties with the police in those days.”

To register a complaint:

Office of the Police Complaint Commissioner

604.660.2385

Vancouver Police Department Complaints

604.717.2670

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra