Sex, drugs and rock and roll-it’s a stalwart trinity. And we don’t seem to have tired yet of watching two boys swapping spit on stage, either. From The Rocky Horror Show (1973) to Hedwig and the Angry Inch (1998), there is a growing body of theatre that figures sexual transgressions right in there with the “rebellious” core of America.

Enter Rent (1996)-a New York musical about sex, drugs, rock and roll, and HIV-positive drag queens.

For its third run in Vancouver (Sep 7-11), Rent brought out the cult-like “Rent-heads” and the city’s glitterati in even measure. That mixture of patrons-ranging from green-haired queerlings to a bourgeoisie hoping to be shocked by deviant behavior-is emblematic of the musical’s confused standing in modern theatre.

Vancouver’s first two glimpses of the scarf-ensconced bohemians of Rent took place in the intimate Vogue theatre and the Queen Elizabeth. This time around, it came to the Centre-where all good musicals go to die.

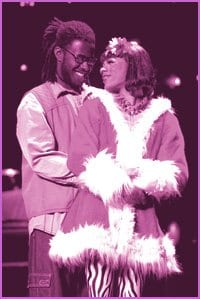

On opening night, the youthful cast (some of them fresh out of their theatre-school eggs) seemed to have difficulty managing their Gap-greeter headset mikes. Audio difficulties (including the band’s mistaken impression that lyrics are best served drowned) were compensated, however, by the genuine love affair these fresh talents had with the material. The words and music of writer Jonathan Larson have become gospel for some.

Larson’s life-work culminated on stage, in the form of Rent. Cribbed from Puccini’s 1896 opera La Bohème, his masterpiece turns the tuberculosis of 19th century Paris into the AIDS of 1990s America. The action relocates to New York’s East Village where three pairs of ragtag Gen-X lovers are squatting in a blacked-out apartment and struggle to paywait for itthe Rent.

(La Bohème itself, if you want to get down to who stole whose idea, was a rip-off of an 1846 book by Henri Murger called “Scenes de la vie bohème”.)

After its storming of Broadway, Larson’s riff on the 150-year-old story went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for best American drama and no less than four Tony Awards in 1996. But Larson died of AIDS a month before the show opened; he never knew what became of his baby.

AIDS is also the key to this musical’s success-the threat of untimely death demands that these characters “figure in love” their last year on Earth, which propels its universal themes of love, hope, and forgiveness. John Finlay once wrote in this paper that “AIDS saved my life.” And doesn’t emergency charge us? Jonathan Larson thought so-so much so that in his final days he continued to work on a musical that implores us to seize the day, to live so joyfully we might surpass the meanest of circumstances.

Eight years later, singer Tallia Brinson plugs one ear and struggles to hear me on a cell phone outside her grocery store in Atlanta. I ask her about her character, Mimi. Mimi is the heroine of Rent, an SM dancer at the local club who struggles with AIDS. It’s curious that the musical (despite being so very gay) is so emotionally focussed on a straight woman and not a gay man. But Brinson’s explanation is adroit: “Not everyone who has AIDS is gay, of course-I think that’s possibly what Jonathan was commenting on. He was telling people it was everyone’s disease. Not just Africa’s, not just homosexuals’. Everyone’s.”

A connection with Al Larson, the writer’s father, allows Brinson to speak with some authority on these intentions. Of Larson senior, Brinson notes, “He’s such a sweetheart. Every cast, he calls his children. He gave a dinner in the East Village for all of us. And he spoke about Jonathan’s commitment to his work. We see that part of Jonathan through his father. It’s very touching.”

Even more touching was the sight of Brinson’s aquamarine spandex pants as she waved her onstage tush beneath a prospective lover’s nose and wondered aloud, “They say I have the best ass below 14th Street. Is it true?” And it is, I’d wager. In the face of AIDS, poverty, and the everyday grunge of anxiety-ridden New York bohemia, this musical insists on sexy, life-affirming exuberance like that. Insists that the party goes on. That there is “No day but today” as one song has it.

That kind of dogged chutzpah is the finest emotional product US writers like Larson offer. “The powerful play goes on,” wrote Whitman, the original gay poet of the US, “and you may contribute a verse.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra