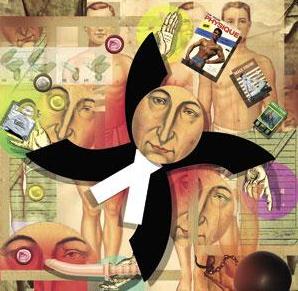

The Supreme Court will release its decision on HIV nondisclosure in the Mabior case later this year. Credit: John Webster

Lawyers for the province of Ontario have taken an extreme position on HIV nondisclosure, backtracking on two years of progress, activists say.

In a 68-page factum filed with the Ontario Court of Appeal, crown attorneys argue that HIV-positive people should face criminal charges for not disclosing their HIV status before sex — even if there is little risk of HIV transmission.

Their position, if adopted, would criminalize HIV-positive people who don’t disclose but use condoms or who have low viral loads. It could also affect prosecutions for unprotected oral sex and other low-risk conduct. That would mean “open season on anyone who has sex,” says Tim McCaskell, a long-time AIDS activist.

“If people have to disclose when there’s no risk, what does that mean? If I kiss someone without disclosing my HIV status, that’s assault? If I shake someone’s hand, that’s assault?” says McCaskell. “If so, then it’s simply discrimination against people who have HIV and AIDS.”

The factum is an abrupt about-face for the province. In February 2011, then-attorney general Chris Bentley agreed to work with a coalition of HIV organizations, known as the Ontario Working Group on Criminal Law and HIV Exposure (CLHE). Their goal was to create prosecutorial guidelines, which would have reined in prosecutions for low-risk sexual encounters.

The guidelines never materialized. But John Gerretsen, who replaced Bentley as attorney general in October 2011, withdrew Ontario from an HIV case heard by the Supreme Court of Canada in February 2012. It was hailed as a good-faith attempt to work with the HIV community and a sign of the province’s ongoing commitment to the working group.

But that’s all been put in jeopardy by the crown’s factum, says lawyer Cécile Kazatchkine, of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. She describes it as “an attack on people living with HIV” and a “betrayal” of the CLHE’s work with the province.

“We are very concerned with the position the Crown has taken. It’s a very radical position, and it’s deeply concerning,” Kazatchkine says. “And it would make prosecutorial guidelines completely irrelevant.”

In a short, written statement, a spokesperson for the Ministry of the Attorney General said it would be inappropriate to comment on either the Supreme Court case or their factum at the Ontario Court of Appeal, since both matters are still before the court. But the ministry also said it would be suspending work on prosecutorial guidelines for the time being.

“It would be premature to address prosecutorial guidelines ahead of this ruling,” Brendan Crawley wrote, referring to the Supreme Court decision.

But the province’s position — withdrawing from the Supreme Court case, then submitting its fiery factum to the Ontario Court of Appeal — is perplexing from a strategic point of view, activists say. The Ontario Court of Appeal will be bound by the decision of the Supreme Court. If the province wanted the court to drop risk analysis from these types of cases, it would have been better served arguing its case at Canada’s top court.

So, did Ontario have a change of heart between February and now? What’s more likely, McCaskell says, is that there are competing factions at the ministry.

When the province withdrew from the Supreme Court case, he says, the attorney general was responding to “an enormous amount of pressure. The attorney general did his job.

“Then, when we got this factum, it looked like the attorney general has gone into hiding,” he says. “What it looks like now is that the cowboys in the Crown attorneys’ office are running the show.

“It’s out of line with what the attorney general [Chris Bentley] said he was going to do. And it’s out of line with what the Supreme Court said 20 years ago. They’re making up the law as they go along.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra