Pride season in Montreal usually means drag shows, outdoor parties and community get-togethers. This year, though, it began with a boycott. In May, a group of over 15 local Sapphic event programmers and community leaders signed an open letter calling for major changes to Fierté Montréal’s policies and staff. The signatories claim that the festival repeatedly “fell short of its promises to the Sapphic community, particularly to racialized members,” by not following through on arrangements made with these groups, including, among other grievances, pulling funding from events at the last minute, refusing to honour contracts and failing to ensure the safety of anti-Zionist protesters. Their demands included the dismissal of executive director Simon Gamache, who they say has refused to acknowledge their concerns, and complete divestment from “corporations exploiting and profiting from associations with the Palestinian genocide.” This boycott marked a tipping point in a longer story of distrust—one echoed in other cities where corporate Pride has outpaced grassroots needs.

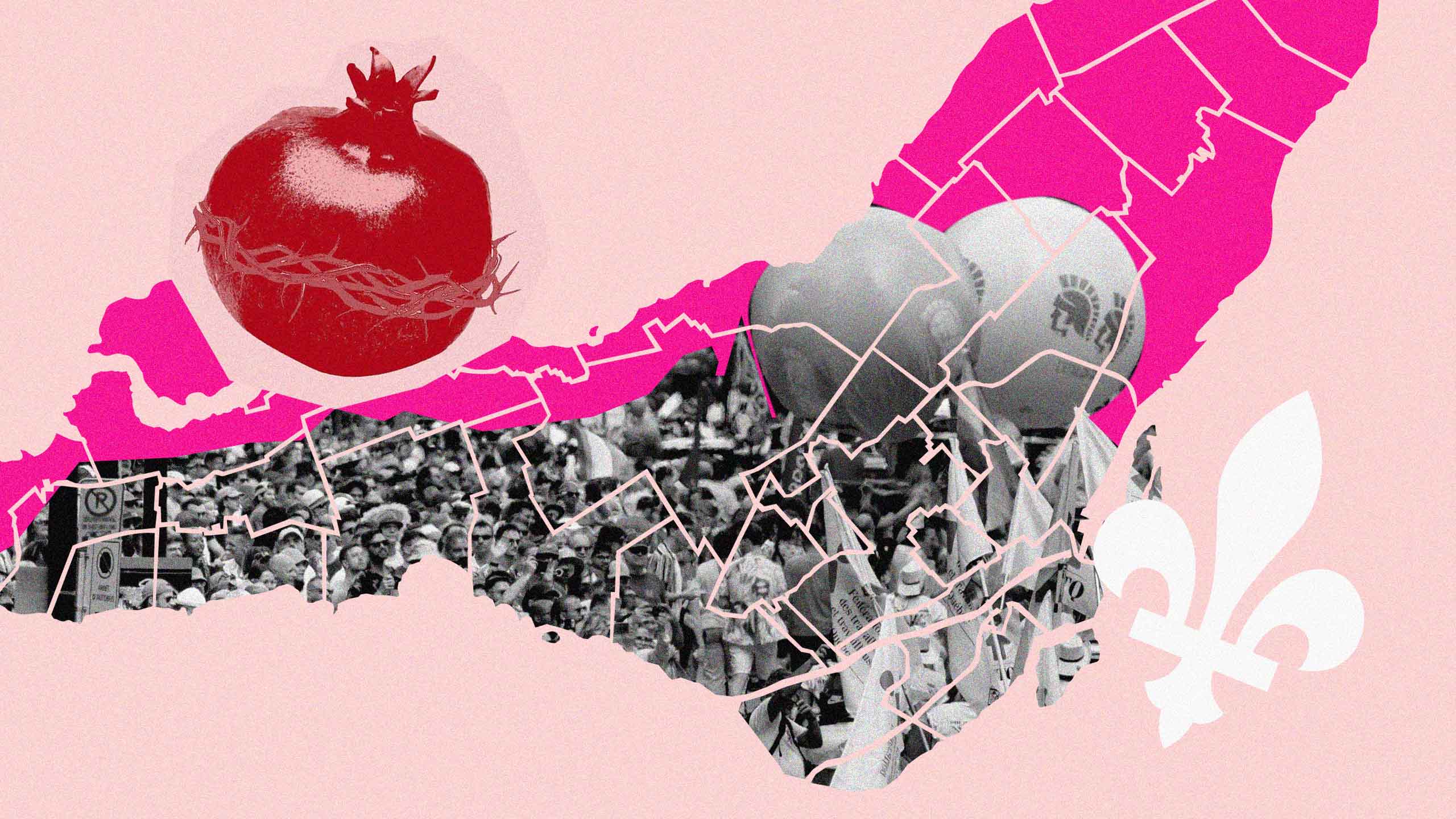

Founded in 2007, Fierté Montréal has exploded in size and scope since its humble beginnings. From 2015 to 2016 alone, attendance jumped from 500,000 to over two million, according to their website. With that scale came big-money partnerships, the kind you’d expect from one of the largest, queerest cities in North America. Backed by brands like Bud Light and Trojan, Fierté Montréal brings in over $7 million in annual income. In 2024, the organization posted its first profit in years after operating in near-constant debt. But that financial turnaround came at a cost. In its 2024 annual report, Fierté cited a “compression of spending in artistic and community programmation” (this is a translation from the French report). Programming accounted for just 9.6 percent of total expenses—the second-lowest category out of eight, just above administrative costs, with the top expenditures being operations and workforce.

That reluctance to invest in and commit to local programming (especially as it concerns the many Sapphic event groups in the city) has caused a rift between the festival and the lesbo-queer community (“lesbo-queer” is currently a popular term amongst the groups involved). In April, as a precursor to the larger open letter, four Sapphic collectives in Montreal released a joint statement calling out the festival for their “harmful practices.” Xtra spoke with two of them.

According to Carolina Montrose, a local programmer who runs Latinx events under the moniker Discoño, Fierté’s staff switched over in 2021. This is when the problems began, she says. Documents shared with Xtra show that in 2022, Montrose helped Fierté’s new team program an event with a popular lesbian dating app only for the festival to pull out at the last minute. Afraid of disappointing her community, she kept working with Fierté until 2024 despite her misgivings. “I thought it was just a me thing, but it was an everybody thing,” she says.

Ray Resvick, the communications director for lesbo-queer events group Messy, describes their collective’s experience working with Fierté in 2022 as “a constant moving goalpost.” Asked to program an event under their collective’s name and with the assurance that they’d be remunerated for their expenses, Messy reached out to talent they wouldn’t have otherwise dreamed of booking due to the high costs of flying them in. “They told us to shoot for the moon, then they didn’t get back to us for two months,” Resvick recalls. In the end, Messy had to pay out of pocket for hotel and travel costs for their performers and was even asked to waive their 15 percent programming fee, claims Resvick. We were told that the contract signed by Messy included a clause stating it couldn’t be shared with outside parties, so Xtra was not able to verify these documents.

Despite the public callout, Montrose and Resvick allege that Fierté Montréal only started to take the boycott seriously when the Quebec Lesbian Network (QLN), an organization that defends lesbian rights across the province, revoked their membership with the festival on May 9. For Cynthia Eysseric, the QLN’s general director, that decision was a long time coming. “We’ve been going back and forth internally about our participation for years because the lesbo-queer community was not being supported. Feedback was given, but nothing changed,” she says.

The open letter prompted the festival to launch an internal investigation, the results of which were not made public, but were presented at a caucus with the organizations involved. “Fierté wants to set up a complaint process by Sept. 30. Beyond that, we have no idea,” says Eysseric of the actionable steps outlined in the meeting. Neither Fierté Montréal nor director Simon Gamache responded to multiple requests for comment on this story. On July 30, one day before the beginning of the 2025 edition, Fierté Montréal released a statement condemning the genocide in Gaza, and announcing that the festival “has made the decision to deny participation in the Pride Parade to organizations spreading hateful discourse.”

As for the future of the festival, Eysseric is somewhat optimistic that Fierté will be able to regain the community’s trust, though not without effort. “Rebuilding [that trust] will take both patience and courage,” she says.

But queer Montrealers won’t be caught without a party this summer. In response to the mass divestment, a new Pride festival is being fashioned from the ground up: Wild Pride, a grassroots event set over three weeks in August, overlapping with Fierté Montréal.

For founding member Yara Coussa, a local queer organizer, this new initiative is about care before anything else. “Even though our event is radical, it’s not going to be about burning down institutions,” she jokes. Events on the docket for Wild Pride include drag queen storytime, a lesbo-queer picnic, teen-only spaces and renting out a public pool for trans parents and their children to attend for a day. The programming focuses on smaller community events highlighting local artists, and the proceeds from ticket sales will go to various aid campaigns, instead of one organization’s pockets. The theme of the festival is “Joy and Revolution.”

Fundraising efforts have already raised over $7,000 through events like drag bingo, arts and crafts raffles and other events catered to the community. Crucially, Coussa isn’t interested in any kind of corporate financial backing. “Montreal is a pretty radical city, and there’s a consensus here that our Pride just can’t be bought,” she says.

When pressed about the state of Fierté Montréal, Coussa admits that they aren’t sure if this iteration of the festival—with its current leadership, structure and policies—has a future with the lesbo-queer community. “I don’t think we will ever agree on what Pride means to us,” she says. “But maybe we can agree on what we disagree on and move on.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra