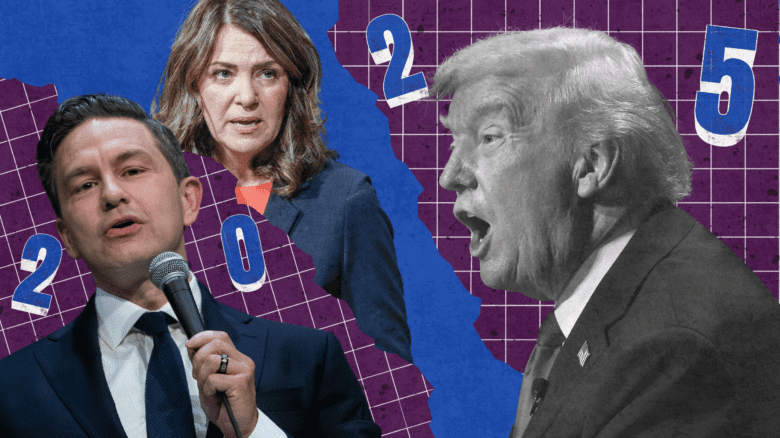

It was not wholly unexpected that the anti-trans resolutions that came up at the Conservative Party’s biennial convention passed with overwhelming majorities—it was pretty much the whole point of why those particular resolutions were prioritized and brought to the floor for the plenary session and voting. With the degradation of how party politics works in this country, what happens at these kinds of policy conventions matters less than it used to, but they are still very much indicative of signals that the party leaders are sending. Through his particular choices and where he is conspicuously silent, Pierre Poilievre is sending a whole lot of signals, particularly to the socially conservative and far-right segments of his voter base that he has actively chosen to cultivate.

Once upon a time, grassroots members would control a political party, and would use these conventions to shape the policy book that the party would run on in the next election. They would have open nomination contests to determine who would run on the ballot for them in each riding. They would have accountability mechanisms for the incumbents. All of that is gone. Because Canadian political parties have steadily Americanized how they choose their leaders, progressively turning these contests into quasi-presidential primaries, Canadian voters allowed the centralization of power within the leader’s office to the point where the power of grassroots members has atrophied. This was never more evident than in the lead-up to the convention, when Poilievre insisted that he’s not bound by any of the policy resolutions that get passed. And this isn’t unique to the Conservatives—it’s a problem within all parties.

In the wake of the convention and the votes, Poilievre continues to play coy about whether or not he’ll make those two anti-trans resolutions part of the official party platform, whenever that gets released, either before the next election cycle or sometime during it.

“We got a whole book of policy resolutions and I’ll be studying them carefully and talking with my caucus members about those policies,” Poilievre told the CBC on Tuesday.

This is wholly disingenuous, of course. This isn’t a decision he’s going to workshop around the caucus room and have vigorous discussions with his campaign strategists over because the mere existence of the policy, and the faux debate over it,are the point. This has always been about the dog whistle and sending a signal to the far-right voters that the party is hoping to attract in the next election under the notion that Conservatives aren’t “united” and can’t win unless they are. It’s something of a false premise—polling analysis has shown that far-right voters who were swayed to start voting for Maxime Bernier and his People’s Party of Canada were generally not disaffected Conservatives, but were rather people who simply didn’t vote otherwise. They’re not being brought back into the tent—the tent is trying to expand to fit them at the expense of the more moderate political centre in Canadian politics.

So long as Poilievre doesn’t denounce these kinds of policies, whether they’re coming from New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, Ontario or his federal grassroots members, he can keep sounding the “parental rights” dog whistle and hope those far-right voters will come bounding in his direction at the next general election. It’s a risky gamble—not just because it shifts the Overton window of what is acceptable discourse further to the extremes on the right, but because these are voters who are not easily placated by winks and nods and occasional symbolic gestures—much the way the Conservatives’ social conservative base has largely been over the two decades since the party was created. After all, anti-abortion activists have contented themselves with the odd private member’s bill from MPs like Cathay Wagantall in the hopes that maybe one day they’ll be able to get one of those back-door abortion-banning bills through and start the slow process of getting jurisprudence that favours their cause.

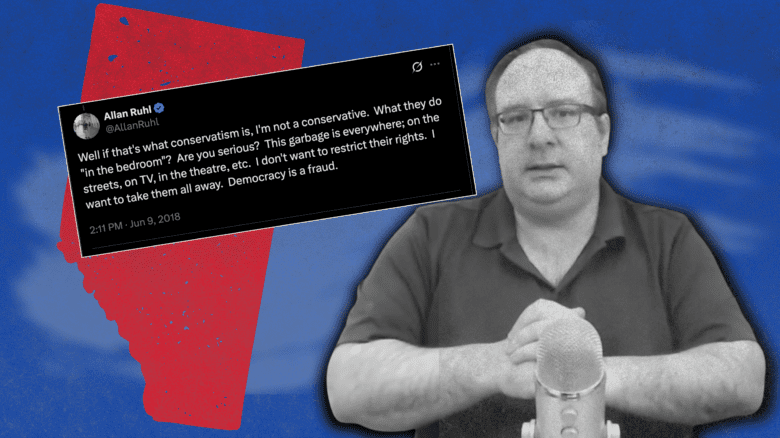

I don’t see the anti-trans far-right voters as being this patient, frankly, and already they are quick to call Poilievre a sellout when he blinks in the face of media criticism, like he did with the “Straight Pride” T-shirt incident at the Calgary Stampede, or when several of his MPs dined with far-right Member of the European Parliament Christine Anderson. But that doesn’t mean he isn’t still trying to court them, whether it’s renewed calls of support for the so-called “Freedom Convoy” members at the convention, including from Poilievre’s wife in advance of his keynote speech, or in the fact that he allowed those anti-trans resolutions to reach the floor, along with a number of completely nonsense resolutions around vaccines, or ending employment equity. If he really wanted, there were plenty of mechanisms that he could have used to “de-prioritize” those resolutions so that they never made it to the final voting plenary, but he chose not to. He clearly wants to signal to them that he’s still on their side, and that he’s willing to say the things that they want to hear, and they do pick up on that message and use it to relay their particular messages to the “normies” out there.

If he really wanted to, Poilievre could shut this debate down in an instant. He could say that he supports the rights of all Canadians, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation, and that trans children deserve compassion and empathy and that he would rather spend his energy dealing with the housing crisis or affordability. But he hasn’t, and he won’t, because that would mean not giving the far-right voters and those swept up in the moral panic over the supposed mutilation and sterilization of children the attention they’re seeking, in the hopes that they will in turn give him just enough votes to oust the Liberals. That silence is a choice, and it’s one that we can’t pretend is just about needing more time to study the policy resolutions.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra