My breath caught in my chest several times watching the Season 3 premiere of We’re Here. The show’s central figures—RuPaul’s Drag Race alumna Bob The Drag Queen, Eureka! and Shangela—descend upon Granbury, Texas, to host a drag performance featuring three civilians. The resulting show took my breath away, sure.

But the episode as whole also elicited genuine fear and concern, particularly in one scene when the trio of queens prepared for their show. They’re shown a series of images of their workspace, secretly taken by locals and posted to Facebook accompanied by violent and threatening comments, including a call to “drag the queens through the sagebrush.”

“[We’re going to] do the show for the people we’re in the show with and for the people who show up to show love,” Shangela says.

“Once we do what we’re here to do, it’s a wrap,” Bob says.

The fear I felt—and heard in the voice of someone like Bob—shook me. But I was so grateful to see it captured, talked about and worked through. In so doing, We’re Here becomes can’t-miss viewing as a dark 2022 for queer and trans people in North America comes to a close.

Credit: Greg Endries/HBO

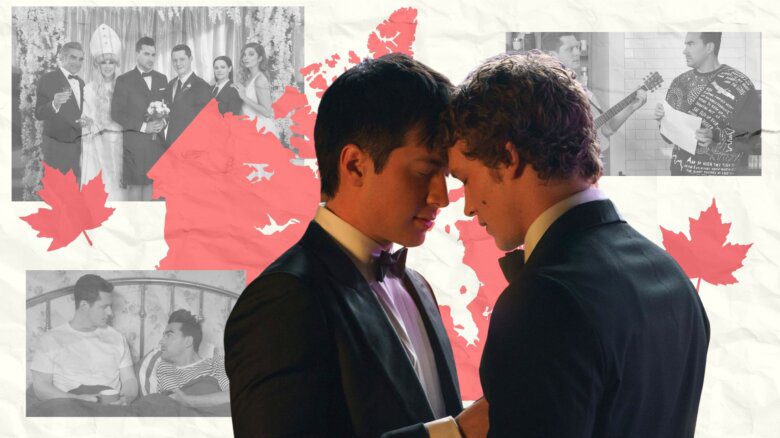

Now in its third season, the We’re Here formula is familiar: the three larger-than-life personalities travel to small towns and cities and empower local activists, allies, youth and even skeptical family members to embrace the transformative power of drag. On the surface, it might sound like Queer Eye meets Drag Race, but the show’s specific emotional depths and high production values have been heralded by critics and fans since its premiere in 2020.

The series’ first season was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Unstructured Reality Program, and its second won Emmys for makeup and costumes. But the series’ third season, which is currently dropping episodes weekly on HBO Max in the U.S. and Crave in Canada, may be its finest—and unfortunately most timely—work.

This brings us back to Granbury, where the production arrived around the July 4th weekend of this past summer. Granbury represents one of the most conservative areas of one of the reddest states, with 81 percent of voters in its district casting a ballot for Trump in 2020. Over the course of their week preparing for a drag show with local community members, the queens encounter cheerful locals bearing signs promoting “drag queen repellent” (spoiler alert: it’s prayer!) alongside active threats to the venue where the show is set to be held.

They’ve faced community pushback in past seasons, but nothing quite like the escalating threats that frame this episode. And yet, the show still went on, opening with a truly iconic Eureka! performance as a giant bug monster set to a cover of Radiohead’s “Creep” and filled with the same sort of uplifting local performances seen in past episodes. But in the wake of the very real stakes, the emotional beats hit even harder.

Credit: Greg Endries/HBO

We are currently in a dark moment of anti-LGBTQ2S+ hate, and specifically animosity toward drag events, with armed militias and fascist organizers actively targeting drag performances and performers. A popular anti-LGBTQ2S+ organization just launched a website to literally coordinate protests of drag events and U.S. state legislatures are also taking aim at drag. And of course, there was the tragic shooting at Club Q in Colorado last month that saw five people murdered.

And it’s not letting up. Just last week, in my supposedly progressive neighbourhood in central Vancouver, a swarm of protestors descended upon a drag queen story-hour event around the corner from my apartment with signs calling for an end to “grooming,” a surreal and frankly terrifying sight for my visibly queer and trans self just trying to walk home from the grocery store.

The old-school stereotype that queers are something predatory or threatening to young people has been emboldened by media figures ranging from the usual Fox News suspects to mainstream columnists. It’s scary to think that in 2022, public sentiment toward queer and trans folks is going backward. Yet that’s the reality we face, with more anti-trans bills than ever being introduced in the past year and far-right groups actively mobilizing to commit violence.

Credit: Greg Endries/HBO

Only two episodes in, and the third season of We’re Here captures that dark reality better than its production team could’ve anticipated while filming this summer. The striking premiere in Granbury is followed up by a second episode that travels to the ostensibly more accepting Jackson, Mississippi. But here, still, street protesters call Bob an “abomination” and accuse the queens of pedophilia. But amidst this, this episode captures the resistance and joy of those fighting for good.

One of the things that makes We’re Here revolutionary is how the production and its central figures meet their subjects where they’re at. A lesser show would position its central trio as teachers, educating small-town folks about cosmopolitan queer culture and bringing a wave of sparkles, high heels and padding to these towns. And sure, there is some of that (I’m always here for a cis straight guy learning how to be vulnerable and tuck!). But We’re Here leans on its stars’ own backgrounds—Shangela coming from Lamar, Texas; Bob hailing from Columbus, Georgia; and Eureka! from Bristol, Tennessee—and the local work being down by small-town queer communities to tell a more complicated story.

“The queer community is big, but they’re scared,” a non-binary high schooler named Lou says in Episode 1. “It’s my job to be a shield for the kids who don’t have one.”

Credit: Greg Endries/HBO

Lou, who started a GSA at their high school and has been doing roller derby since they were six years old, is on a personal crusade against banned books in Texas. They’re just one example of some remarkable casting in these first two episodes. Another is Deshay, a Black trans musical director who left Granbury after being let go by the church they worked at. These local queer figures appear alongside allies like Episode 1’s Adrienne, a hairdresser and local Democrat and Episode 2’s Chris, a weed-shop worker who wants to show how straight cis guys can be allies (his shift from calling gender-fluid Eureka! “bro” to “chick” after she asks, is genuinely heartwarming).

Together, the show paints a complicated portrait of the queer reality in smaller and more conservative areas. It’s something mainstream news media has gestured at, but the unique documentary-style, reality-TV format of We’re Here allows for a comprehensive and unflinching look at a world full of real threats, but also the potential for joy and breaking through our communication bubbles.

As Bob says in Episode 2: “It’s not about the drag, it’s about amplifying your voice, telling your story.” As our community stares down a terrifying time, thank god for the work We’re Here is doing to tell that story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra