When I was in college, I didn’t trust myself to help tell the stories of my community. Though I’ve always found it important to document how queer Latine folk have continually found, or made, a way to survive in this world, everything around me said that I wasn’t the right person to do it. During an anthropology class, my non-Latine classmates felt as though they had a more objective perspective on researching my culture because they were outsiders. According to the lecturer, my perspective could be biased, as I would be more of a participant in my community than an observer—making it harder to describe the cultural norms that supposedly had always been second nature to me.

I left class that day frustrated. Frustrated at myself for knowing that the debate was flawed, but not having the words to refute it. Since I couldn’t shut down the argument immediately, frustration soon turned to self-doubt. At the time, I wasn’t able to articulate the value that my perspective brought in helping my community preserve its cultural memory.

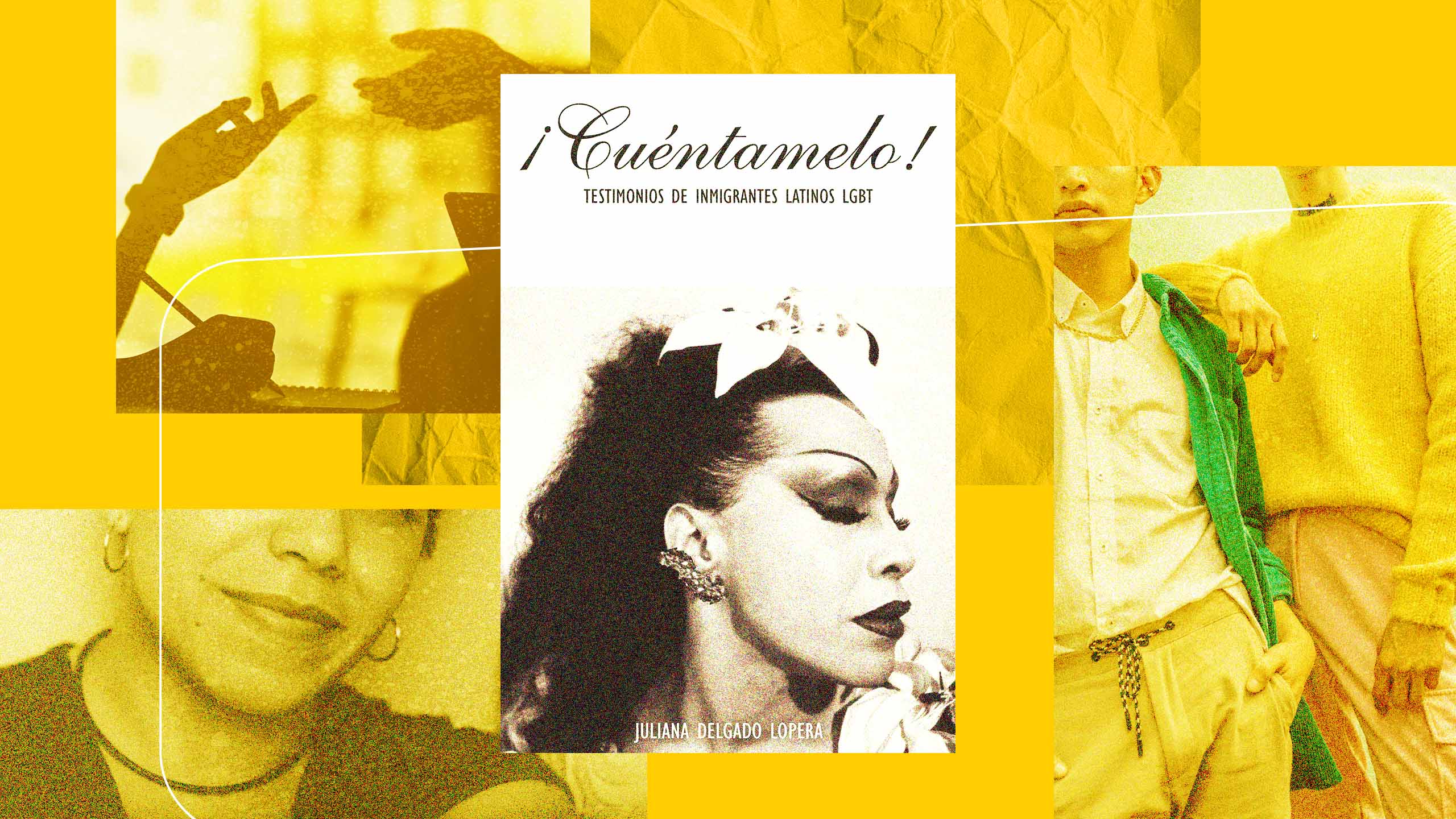

Then I discovered Julián Delgado Lopera’s ¡Cuéntamelo!: Oral Histories by LGBT Latino Immigrants. The award-winning anthology, first published almost eight years ago, rallied around the community member as archivist, a radical re-imagining that made clear the unique value that I could bring in documenting queer Latine stories. I learned that outsiders don’t understand the historical lessons that my generation and future generations of queer folk need to learn from our queer elders, but I do. Realizing that I could help address this need, just as Delgado Lopera did in their anthology, moved me to collect oral histories.

“If we forget to tell our stories, we forget that we exist.”

¡Cuéntamelo! grew out of a group of queer Latine immigrants who came to the U.S. throughout the 1980s and ’90s and built chosen families in San Francisco. When Delgado Lopera became a part of those families, they gained access to a queer culture and history that seemed invisible to them before. Inspired, Delgado Lopera wrote an article about the collective for a 2013 SF Weekly cover story as a way to carve out a place for Latine queer elders to integrate their stories into the mainstream queer historical narrative.

The stories told in these oral histories spanned the entire lives of those interviewed, from the inklings of queerness that they felt in childhood to the arduous process of applying for asylum and restarting in the United States. Common threads included how the art of drag impacted their identity formations and the communal loss from the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

After publication, the oral history project was expanded into ¡Cuéntamelo!, an anthology of seven oral histories from queer Latine immigrants in San Francisco over the age of 45. The focus on our queer elders was intentional, aiming to fight the glorification of youth in queer culture by honouring those who created the community we take pride in today. The collection’s first print run sold out on its release day in 2014, and went on to win the Lambda Literary Award for best LGBTQ Anthology in 2018.

These stories did not feel like dusty relics stuck in the attic; they punched out with urgency, demanding to be shared widely. The first oral history in the work was from Adela Vazquez, a matriarch of the trans Latina community in San Francisco who advocated for her sisters at the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. She held court in her living room as the legal reality show Caso Cerrado trumpeted from the television nearby. The later pages gave rise to oral histories from the chosen family that Delgado Lopera nurtured and nourished all these years since. Together, those interviewed provided context for the wide breadth of the Latine experience.

Delgado Lopera’s close ties to their interviewees were as inspiring to me as they were shocking. They challenged the idea that their intimate proximity to those interviewed was a disadvantage. Each oral history starts with a short description, clearly informed by a personal relationship with Delgado Lopera that draws the reader to settle into the conversation with ease. It is this trusting bond born out of community that has Marlen Hernandez, a drag queen that immigrated from Cuba, declare to Delgado Lopera that “I am very open, Mami, I tell my life as it is.”

“These stories did not feel like dusty relics stuck in the attic; they punched out with urgency, demanding to be shared widely.”

I was inspired to start forging similar relationships in my own life as a community archivist in Philadelphia. My first oral history was with Deja Alvarez, a trans rights activist who ran for city council in 2019 and Pennsylvania State Senator in 2022 with the goal of becoming the state’s first trans Latina legislator. In our conversation, she detailed the different barriers she faced in running her historic campaign, including her difficulties fundraising as a trans candidate, and her financial inability to leave her day job in order to fully dedicate her time to the campaign. Alvarez’s experiences as a politician had to be documented to guide the next person who follows in her footsteps, and like Delgado Lopera, I wanted to document this story in our cultural memory.

The queer elders in ¡Cuentamelo! clearly laid out what is at stake if we let others tell our stories. Community is intentionally built, and the most effective bulwark against a capitalist system that exploits communities of colour. If we forget to tell our stories, we forget that we exist—the bulwark weakens. Vazquez described in her oral history the jarring effect of finding a fractured queer community whose members were isolated from one another. During the HIV/AIDS epidemic, she performed in drag shows at a hospice in San Francisco, and it was during those performances, as she told Delgado Lopera in her oral history, that she realized, “there were a lot of us, nina, [and] that trans people were not organized, and there was nobody representing the Latinas as a community.”

Protecting our community from erasure, preventing that feeling of isolation amongst the larger queer Latine community is my renewed mission as an archivist working with the Philadelphia HIV/AIDS Oral History Project at the William Way LGBT Community Center. Delgado Lopera’s collected oral histories helped me realize that being cut from the same cloth and woven from a shared history is a critical need in this work.

In the anthology’s final oral history, Nelson D’Alerta, one early transformistas that performed at Esta Noche, the first Latine gay bar in San Francisco, said that he “had this idea of opening the salon in my house once a month, so that all my queer Latinos can come sing, play the guitar, perform, read, whatever.” It is a privilege and responsibility to play a part in preserving the voices that fill up that salon.

This story was published with support from Critical Minded.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra