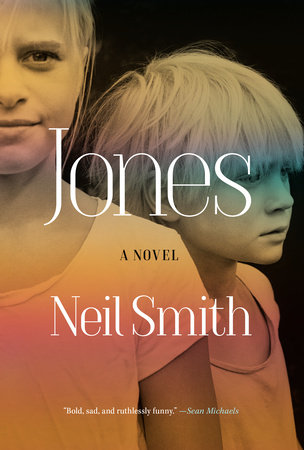

Brace yourself for the experience of reading Jones, Neil Smith’s latest.

The novel is a harrowing, semi-autobiographical take on a tortured childhood and adolescence, and the survival strategies of one brother and sister, as they attempt to escape from a family rife with alcoholism, abuse, incest and suicide.

Eli and his older sister Abi begin plans to bolt from the Jones Family (or “Jones Town,” as it’s referred to in the book) early on. Their idea is to flee to Manhattan, where the cool people live. Their father is a severe alcoholic (with oft-repeated plans to get sober) and their mother is an eccentric narcissist. Making matters more complex, the family keeps moving, so making friends or putting down roots of any kind is nearly impossible for the kids.

Credit: Courtesy of Penguin Random House

Smith, who lives in Montreal with his long-time partner Christian Dorais, manages to fuse the devastating parts of this severely dysfunctional family’s tragedies with comic touches. It’s an impressive feat, given that his source material is clearly his own life. In a gut-wrenching move, the novel contains a photo of the author’s actual sister when she was a child, with a dedication to her memory. The emotional burden is personified by the fictional sister, Abi, and can be felt throughout the book. She confesses to her brother at one point, “It’s like every step I take in the world, there’s a big pair of hands pressing down on me … it’s unbearable sometimes … the weight of it.”

Smith’s own trajectory as a writer is remarkable. In his mid-thirties, while working primarily as a translator, he decided to take a night class in writing. His teacher liked the short stories he was penning, and urged him to submit them to journals; this led to publications, nominations for awards and then a bidding war by several Canadian publishers to put out his first anthology. The result, Bang Crunch (2007), in which a gay teen made an appearance, made the best-books-of-the-year lists for both the Globe and Mail and the Washington Post. His 2015 novel Boo won the Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction.

Because the queer author’s work is often quite fantastical, Jones represents a significant break in tone and style; it’s starkly realist and feels based on many of the author’s own experiences. For children of the 1970s, the book conjures an array of familiar cultural references, from “Disaster Movies that feature Charlton Heston” to One Day at a Time, to the Osmond and Manson Families to the 1976 shot-in-Quebec Jodie Foster movie The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane. Montrealers of a certain age will recognize Smith’s description of police brutality at the 1990 protests against a police raid on a gay party space, but Smith chose not to have his protagonist participate in the activism he himself did during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

We spoke on a Montreal patio on a hot July afternoon. Sporting long hair, with Shaun Cassidy-esque boy-next-door good looks, Smith gives off such a gentle vibe, it’s almost impossible to believe his childhood was so rocky.

You once said that you weren’t interested in writing about yourself. Yet here you are.

I think at first I avoided writing about myself because for me, writing was an escape from my life. At one point I was still suffering from a lot of anger from my childhood. I went to see a therapist who said, “You know, you’re a writer. Maybe you should write about this.” I decided I would give it a shot. I needed to write about it in a way that would give me some distance between my own family and the family in the book. Ergo the change in name. It was as if I were hiring actors to portray us. So instead of visualizing myself or other family members, I visualized people who looked vaguely like us. They were 75 percent us, and that left me to create the other 25 percent. That gave me the liberty to tell the story without it becoming too devastating. I probably will never write about myself again. I think this is the one and only project like this, just because my childhood was so unusual. But I never really want to do it again. I really love making stuff up. My previous book was entirely made up. That’s why I avoided writing about my family.

I’m struck by how many great memoirs of family life have been written by queer authors: Saeed Jones, Augusten Burroughs, Garrard Conley. Were there any you thought about while writing Jones?

No. The one that I thought about was The Glass Castle [the 2005 book by Jeannette Walls], which is not queer. But she comes from a really fucked-up family, too. But it’s a memoir and I knew I didn’t really want to write a memoir. I wanted to write a novel. I didn’t want to have to write everything in chronological order, I wanted the freedom to move events around, to eliminate characters. I had an older brother who committed suicide, too, and I felt the book could not contain another death or any more sorrow. So I had to eliminate him. I wanted to balance the book’s sorrow with humour, for it to have a light touch, if that’s possible.

I think you manage that well. It’s a hard thing to carry off, but you do it in the book.

That’s what childhoods are like, and what life is like. Even when my sister was dying, there were funny moments. Even in those scenes, there was levity. At one point a nurse says, “Only the man upstairs can say when your sister will die,” and I thought she meant that the doctor had an office upstairs. It took me a long time to figure out that she was talking about God. I told my sister, but of course she was in a coma, so couldn’t understand. It had to be funny at times because my sister was funny. It would be a betrayal of her if the book was overly earnest. There had to be some laughs in it, too.

There’s that scene in Pedro Almodóvar’s Bad Education where a boy acknowledges the abuse the priest has done to him, and then he turns around and launches into a rendition of “Moon River” in Spanish, and the audience bursts into laughter. The juxtaposition of emotions is startling, and it’s something I got reading your book too.

Which is what I wanted. Early in the book, a boy is in a depanneur, and he steps out and is met both with the clash of the air-conditioned cold inside and the heat outside. I wanted the book to be a meeting of those two different things as well.

The family is rich terrain for queer writers. On the one hand, the structure of the patriarchy is a place where many of us have felt displaced or oppressed. But many of us have profound stories of bonds with specific family members.

I was thinking of that when I wrote the book. At one point the sister says that the family is the ultimate F word. I’ve always felt that, because of the kind of family I grew up in. For me the family is not a word that feels protective in any way. Even the words “mother” and “father” or worse, “mom” and “dad,” I avoided using in the book. I call them by their first names rather than calling them Mother or Father, to avoid feeling that they have some kind of power over me. It’s a critique of those kinds of families. I can’t watch sitcoms because of the way love is shown in those shows. When I watch a movie or read a book where a family is close-knit, it angers me. Maybe because I didn’t grow up in that kind of household, and maybe I’m angry about not having had that.

So, The Waltons doesn’t work for you.

No, that’d be torture. In the book, Eli and Abi love reading La Belle Bête [Marie-Claire Blais’s 1959 novel] because it’s the worst possible family that anyone can imagine, and they actually outdo the Joneses, which is why they love that book so much. That’s the only kind of family saga that I could watch … ones like that. I really can’t relate to families that are loving. My family in particular was so outrageously abusive that when I speak to people who think they’re from abusive families, and when they tell me what they think is abusive, it’s so minor compared to what we had to go through, that I just have to laugh.

It’s funny that you refer to life with the family in the book as “Jones Town.”

I think I’ve always been trying to escape from Jones Town, ever since I was a little kid. I think by writing this book, I was hoping to escape from it. I do feel now that I’ve finished it, these issues are not weighing on me as much as they did a few years ago. I feel that it helped me. That was originally the aim, to let me get free from it. I am now talking about it because the book is coming out, but I don’t feel the same anger that I once did years ago, where I was grasping at ways to feel better and to control the anger. It was cathartic. Part of writing a book is that you have to take a character from point A to point B, so whether you’re making stuff up or if it’s about you, you have to move things forward. I certainly cried when I was writing certain scenes. Especially writing about my sister’s death. I’m glad that I did the book and got it over with. I’m looking forward to new projects that will have nothing to do with my life!

The book has a very queer sensibility—it’s funny, dark and cynical.

I think it’s a queer book, but from the family itself, not so much from the sexuality of the kids. It’s queer in the old sense of the word. When I was growing up, being queer was not traumatic for me, what was traumatic was growing up in this family. I didn’t ever go through a period where I was uncomfortable about being queer. I was quite bisexual when I was young and quite fluid about who I slept with. It didn’t cause a problem for me. I never suffered as a result. I think I was like that because of the family I grew up in. What was going on around me growing up was so horrifying that my being queer, and my sister also had relationships with women—none of that bothered me.

I really appreciated the way you structured the book: each chapter is a different place your family lived in, or that the central character lived in. Adolescence is hard enough, but the lack of any kind of sense of being rooted comes across in the book.

It was difficult, because we were moved out of schools all the time. In the early years I changed schools every grade. I came back to Montreal after my parents split up. Some years they wouldn’t even put me in school, so there are gaps in my education. And then I’d go from Montreal to Salt Lake City to a hyper-religious environment, which was brutal. Just as we’d start to settle into a place, we’d have to move again. As a kid, you had no control over this. My parents didn’t care about my losing friends or missing education. When I was in Chicago I made some very good friends and then it was over so quickly.

You and I are about the same age and have lived in Montreal for some time. You describe the 1990 demonstration against the Sex Garage raid that was broken up brutally by police, and I was at that protest, videotaping it. That was organized by ACT UP Montreal. But one thing that surprised me is that you don’t really get into HIV or AIDS at all in the book. My memories of that period as a gay man are overwhelmingly about HIV, having friends who were dying and also being consumed by anxiety about seroconverting myself. It seemed glaring to me that it’s not in the book.

I was a member of ACT UP and attended many demonstrations, and at the time I spoke in high school classes about safe sex practices. I didn’t include that in the book for a couple of reasons. It took away from the family’s story. There was already enough death and sorrow in the book, and I felt like including it would have slowed down the arc of the book. Like my older brother’s death from a heroin overdose: there’s only so much I felt I could include. For this book it was extraneous to the story I was telling.

Did you write the book in part to help others who may have experienced something similar, or was that even on your mind while you were writing it?

There aren’t that many books that get into incest, actually. Over the years I haven’t met many people who have had the experiences that I have. I know that incest between a child and parent happens, but people are not that open about it, or it’s not as prevalent as alcoholism or anorexia, which I also touch on in the book. I wanted to talk about incest, to talk about what actually happens to families where this happens. The parents do monstrous things, but some people have told me that they are drawn to the characters, even if they do awful things. I wanted that to be portrayed honestly, too, so people would understand what it’s like to be in a family like this. We have some Hollywood portrayals, but they aren’t usually very honest. I wanted to show a person trying to escape a family like this, yet somehow constantly being pulled back into the drama, year after year. Some people have said, “Why didn’t you just break off with your family and never see them again?” And I did try to do that, but I never really managed to. I also suffered from a lot of guilt about not doing more for my sister. There’s a lot of guilt when people go through these situations. My leaving was a means of survival. But there was a lot of guilt.

Your protagonist gets his revenge in a wedding scene toward the end of the book. Was that queer fantasy or did it actually happen?

I think my act of revenge is this book. Some of the book is made up and some of it are things I wish I could have done but didn’t do. It’s my own way of rewriting history. Some of the weirdest stuff in the book is true.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra