“Don’t dream it, be it.”

Writer Richard “Bugs” Burnett was in his early teens when he first saw the Rocky Horror Picture Show at the Seville Cinema in Montreal. It was the late 1970s, just a few years after the cult classic had premiered in 1975, and he had never, in the span of his short life, seen anything quite like it.

With its gender-bending costumes, sexually fluid interactions and otherworldly plot, the film unapologetically put queerness on display at a time when it was just not done. For young queer teens like Burnett, seeing it for the first time was nothing short of a revelation.

“Finally, on the big screen, I saw something that kind of reflected my own life and my own sexuality,” he tells Xtra. “It was an affirmation, it was a validation of identity, and it basically said, ‘You, Richard, it’s okay to be queer.’”

Like Burnett, I first saw Rocky Horror in my early teens at a late-night screening with my friends—though my first exposure took place more than 30 years after his. I had been involved in musical theatre from a young age and had an idea of the film’s reputation (plus I knew all the words to “The Time Warp”), but I had no clue what was in store for my friends and me when we tipsily walked into Montreal’s Imperial Cinema on Halloween in 2011.

The experience transported me to what seemed like an entirely different planet—one with few social conventions and zero judgment. Suddenly, despite my teenage awkwardness, I felt inspired to stand out instead of fit in. And as I returned to Rocky Horror every Halloween through most of my adolescence, dressed slightly more provocatively each time, I gradually began to wonder what exactly it was about this strange movie that spoke to people—especially queer people—across generations.

At its core, I think the answer is community—which, at a Rocky Horror screening, consists of the actors on screen, performers on stage and fans in the audience. This eclectic group of freaky, open-minded, sex-positive and overwhelmingly tolerant people was unique in the ’70s, and that spirit is preserved among the film’s fans to this very day. Watching Hollywood actors in drag-like getups dance and sing about gender fluidity and pleasure may be enough to make you feel just a little more comfortable in your own skin, but doing so while surrounded by hundreds of other eccentric humans who encourage you to embrace your weirdest traits is straight up revolutionary.

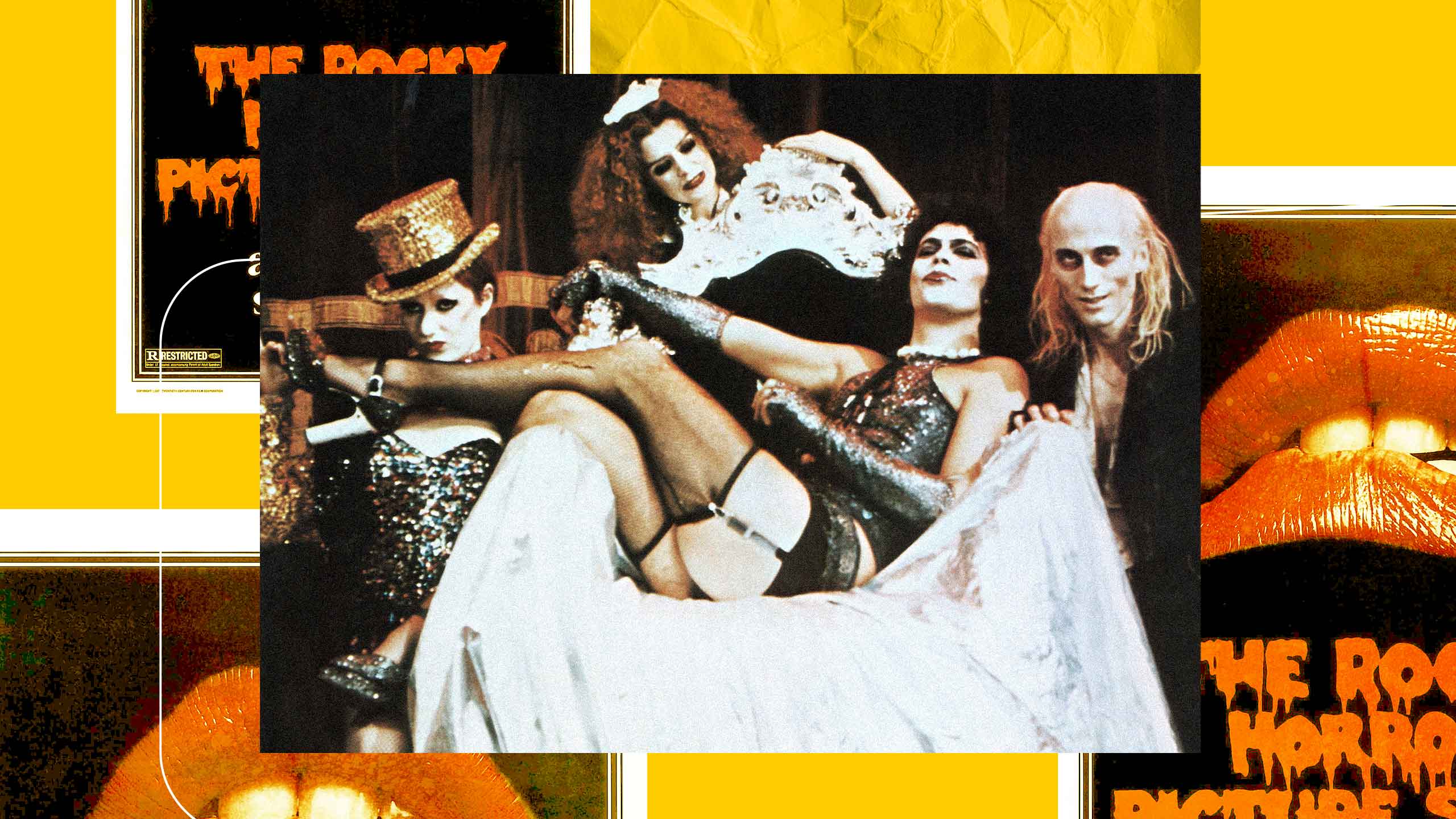

At first glance, Rocky Horror is an outlandish story about a couple seduced by an alien mad scientist “transvestite” named Dr. Frank N. Furter (Tim Curry) after their car breaks down outside his castle. Stranded and phoneless, old-fashioned and wholesome Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon) have no clue what they’ve gotten themselves into when they first knock on the castle door to ask to use the phone—they’re as naive as someone attending a Rocky Horror screening for the very first time. They soon discover that they’ve crashed the “Annual Transylvanian Convention,” a gathering of equally out-there characters hailing from the planet “Transsexual” in the galaxy of “Transylvania,” including Riff Raff (Richard O’Brien), Magenta (Patricia Quinn) and Columbia (Nell Campbell).

Throughout their adventures at the castle, the couple meet Dr. Frank N. Furter’s latest invention, a creature named Rocky (Peter Hinwood) who is meant to be the perfect male specimen; witness the murder of Eddie (Meatloaf), Dr. Frank N. Furter’s former lover and Columbia’s current partner; partake in a few catchy musical numbers; and, as the song lyrics go, learn to “give over to absolute pleasure.” The film, written by Richard O’Brien and based on his 1973 stage musical of the same name, was meant to be a parody tribute to the science fiction and B-horror movies O’Brien had loved since childhood.

Though it initially drew small audiences—some of its planned openings were cancelled—viewers started to catch on when the film was relaunched as a “midnight movie” in 1976. The weirdness started to kick in: audience members began shouting sarcastic one-liners back at the characters on screen and throwing props like toast, water and toilet paper in response to particular lines or scenes in the movie. Then came the “shadow casts” of live costumed performers acting out the film on stage while the movie played in the background. These participatory elements quickly became traditions, and Rocky Horror screenings turned into an interactive community experience that encourages audience members to dress up, sing along and act out.

“You were in a room full of other people who were just like you in some way, and it was a celebration,” Burnett says. “Everybody was celebrating one another. It really was cathartic. It was fun, it was really fun.”

Pure, unadulterated fun is exactly what my ninth-grade friends and I were after when we bought our Rocky Horror tickets on a whim. With alcohol-filled water bottles tucked in our pockets and, underneath our jackets, the most risqué outfits we could find, my girlfriends and I walked into the theatre hoping for a wild, parent-free Halloween where we could let loose. And boy, did we have one.

“Everybody was celebrating one another. It really was cathartic. It was fun, it was really fun.”

By day, we attended a strict high school for high-achievers that required us to wear modest uniforms (and punished us if they weren’t worn just so). The Imperial was the antithesis of our conservative grey kilts and the norms that were forced upon us in our everyday lives. We looked around and saw people of all genders dressed in lingerie, audience members wearing nothing but duct tape and more feather boas than we could count. People were rowdy and loud, greeting one another from across the room with shrieks and hugs and costume compliments. At first, I was taken aback by it all, but the discomfort I initially felt quickly turned to excitement when I realized I, too, had permission to let loose. I breathed a sigh of relief, took a gulp of my Smirnoff vodka, took my jacket off to reveal my fishnet tights and skimpy bodysuit and waited to see what other unpredictable adventures were in store for us.

Minutes later, when the host asked everyone who was a “Rocky Horror virgin” to stand up so they could paint giant red Vs on our faces in lipstick and welcome us with a collective “fuck you!,” I knew I had arrived.

At the time, my friends and I all identified as straight—I discovered my queerness and came out as bisexual years later—but going to see Rocky Horror on Halloween over several school years was liberating. While our school continuously reinforced the idea that our bodies were something to be ashamed of and should always be covered, Rocky Horror encouraged us to embrace our sexuality as young women coming into our own. There were no taboos at a Rocky Horror viewing, and I loved every second of it.

I attended Rocky Horror screenings every Halloween from age 14 to 16, and then again when I was 19 after moving to Toronto. Each year my outfits got slightly more revealing until I eventually purchased a “slutty maid” costume to look like Magenta. And each year that I returned, I had better memorized the lyrics to the music—which would make even the world’s biggest tight-ass want to get up and dance—and the cues for the callback lines. Every year I went back, I felt even more at home. Though the pandemic has prevented me from gathering with the Rocky Horror community for the past couple years, depriving me of that sense of liberation I’ve been missing, I hope more than anything that I’ll get to do the “Time Warp” again in the company of fellow die-hard fans next year.

Of course, Rocky Horror was far less radical in 2011 than it was in the ’70s. Watching that first screening was not the first time I had seen queerness on the big screen, like it had been for Burnett, and it was definitely not the first time I was exposed to sexually liberated characters. But it was the first time I was in a room filled with like-minded weirdos. And I have no doubt that the Rocky Horror experience touched the part of me deep in my subconscious that already knew I was queer, helping me to inch just a little bit closer to the place of self-acceptance I would eventually reach.

That’s what Rocky Horror has done for so many of us: it has made us feel proud of the parts we’ve been taught to hide and given us an environment in which to celebrate our oddest, queerest qualities without shame. It has given us permission to give the middle finger to all of society’s shoulds and don’ts, all while looking absolutely fierce doing it.

“More even than what was present in the film, it was what was present in the culture surrounding Rocky Horror, and I think that’s what makes it enduring,” says Fairlith Harvey, who’s been hosting and running Rocky Horror shadow cast performances at The Rio in Vancouver for more than a decade.

Harvey first discovered Rocky Horror in the late ’90s, when they were—you guessed it—a young teen. But it wasn’t until they moved to New York City for university and performed in a live stage production of the original musical that they discovered the life-changing, welcoming community of queerdos that comes along with it.

They say the theme of Rocky Horror and the culture that surrounds it can be summed up in the title of one of its songs: “Don’t Dream It, Be It.”

“It’s an incredibly powerful message,” Harvey says. “It’s so important and I just internalized it. And for a long time in my 20s, I didn’t even realize how much Rocky Horror was kind of this subconscious mantra, but it gives me courage.”

As is the case with pretty much any piece of art that came out decades ago, Rocky Horror is problematic. The language, for one thing, is completely outdated (can you imagine actually using the word “transvestite” today?), and the way the film carelessly blurs the sexual orientations and gender identities of its characters would today seem disrespectful. As Harvey points out, the consent that Dr. Frank N. Furter gets before fooling around with both Brad and Janet is dubious if not non-existent. The cast is also overwhelmingly white.

Life-long Rocky Horror fan Sarah Kulaga-Yoskovitz was introduced to the soundtrack by her parents in 1995 at the age of two and has performed in the original stage musical in Montreal. She says the live, community-driven aspects of both the shadow-cast shows and the musical productions keep it fresh and relevant so many years later. With thoughtful casting and inventive staging, modern-day theatre companies find new ways to bring Rocky Horror into the 21st century. In one of Harvey’s productions, for example, they worked hard to build consent into the staging of the scene where Dr. Frank N. Furter seduces Janet and Brad.

“The Rocky Horror experience taught me to be ashamed of nothing, to indulge my curiosities and to say ‘fuck you’ to any forces that try to tame me.”

“It does become this live art that is constantly evolving and never-ending,” Kulaga-Yoskovitz says. “People really need that. If they’re going to keep coming back to it, it needs to evolve and they get the chance to see themselves in that and see themselves evolve through that.”

Like so many fans, Rocky Horror helped Kulaga-Yoskovitz embrace her sexual orientation; participating in the live show allowed her to be a part of a queer community for the very first time.

“That community of both queer and non-queer artists introduced me to the queer community,” she says. “Before Rocky, I hadn’t come out. I was exploring, but it really welcomed me into a space where you feel like you can be anything and look like anything and love anything, so it was a huge impact for me being a part of it in that way.”

Since its release 46 years ago, The Rocky Horror Picture Show has endured as a cultural phenomenon. At the tender age of 14, when I was just beginning to figure out what kind of woman I wanted to become, the Rocky Horror experience taught me to be ashamed of nothing, to indulge my curiosities and to say “fuck you” to any forces that try to tame me. The screening events that are still held around Halloween across the continent are a testament to how impactful the film—and more importantly, the culture its fandom has created—has been for nearly five decades.

Once discovered, people keep going back for more. As Burnett describes it, being a Rocky Horror fan is like having a sweet tooth; every now and then you get a craving, not just for the movie but for that welcoming, freeing feeling that comes with attending a Rocky Horror event. The only way to satisfy it is to watch the film surrounded by Rocky-loving peers. And the repetition of the tradition provides some comfort—knowing you can come back year after year and feel that same sense of freedom again and again is exhilarating.

As Harvey so aptly puts it: “If you’re a Rocky Horror person, you’re a Rocky Horror person for life.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra