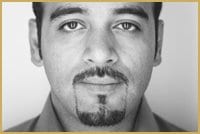

When Peyman Khosravi speaks, the conviction in his voice and the passion in his stories are so full-bodied, you can almost taste his truth. He has put his life in danger, his finances in ruin and the safety of his family in jeopardy. He has taken these risks, with his friend and co-producer Babak Yousefi, to produce I Know That I Am, their new documentary about the lives of transsexual women in Iran.

Both men say–only when asked directly–that they are heterosexual, but the question seems inconsequential to them.

“It all comes down to the fact that as human, if you see somebody fall, most of us would offer a hand, would help them up,” explains Yousefi. “That is what we’re doing. To have offered a hand to somebody, we feel entitled to be in a position to say ‘we’re doing our share, everybody else should do theirs.'”

Khosravi and Yousefi are two incredibly brave men who don’t consider themselves praiseworthy. To them, the courageous ones are the subjects of their film.

Two years ago, Khosravi was a successful television director working in Iran on everything from sitcoms to teasers. “I had everything you could wish for in life,” he says in Farsi through his friend and ally Yousefi. “I had a job, a home, a car, a family, a life… In Iran, a small percentage of people have these conveniences in their lives. The rest suffer because of injustice.”

Working for Persian television, Khosravi was called on to do interviews on various subjects. Themes like addiction and prostitution, deemed controversial by the authorities, had to “follow certain guidelines in terms of what got discussed and what got dropped,” he explains. “I was assigned to a project on what was referred to as ‘street women.’ That was when I met my first transsexual.”

In time, Khosravi met a transwoman who told him of human rights abuses at the hands of Iranian authorities so widespread among transwomen that he felt he had to do more than just record her words. He needed to expose the stories of trans-Iranians to the world.

“When I initially met this person and started speaking with her, I realized what an illness of society this issue has become,” he recalls. But earning the trust of transwomen came slowly. “It took me a good six months to actually be able to show them my interest,” he says. “They actually shadowed me for a while to see what kind of work that I do and how I deal with issues such as prostitution and addiction. They wanted to gauge me as a person by looking at my work… When they realized that I am actually a person who cares, who is paying attention to the issues, it really encouraged them to talk with me.”

Having gained their trust, Khosravi spent much of his spare time interviewing transwomen and transmen in great secrecy. Some interview subjects spoke with their backs to the camera, some with their faces hidden behind burqas, all of them well aware of the risks they were taking by speaking on tape about human rights abuses by Iranian authorities.

While some have chastised Khosravi and Yousefi for making a film that exposes their subjects to such risks, it is the subjects themselves who come to their defence. While unable to contribute directly to this story, their words in the film provide incredibly articulate, poignant responses to such challenges.

“I hope for the courage to speak out,” says Naz in the film. “I hope to be able to say who I am. Sooner or later I’m going to die, with or without dignity. It is better to go with dignity.”

Her story and the stories of women like her are simultaneously haunting, frightening and inspiring. Their struggle stays with each viewer long after the credits roll. Unlike fiction, there is no happy ending; at least not yet. In fact, things could get much worse before they get better.

As he gathered their emotional stories on tape–tales that often detail police oppression and abuse–Khosravi knew that news of his project had to be hidden from Iranian authorities.

Last year, Khosravi was on his way home from a visit with his parents after showing them some of his interviews. The filmmaker received a frenzied call from one of his neighbours telling him that the authorities had broken into his house and appeared to have confiscated all of the footage for his film.

“Whatever I had, they took away,” he says, clearly reliving that night in his mind. “All we have left is the film I took to my parents’ house. At the maximum, I had about 30 percent of the footage on me, the rest was confiscated.”

When asked just how difficult it was for him to lose so much of his work, the eloquent filmmaker struggles to find the words. “You ask if my soul was ripped apart. You describe it perfectly,” he says. “Some of the stolen interviews were really the most important parts of this film. You can only imagine–with the hardship that comes across in the movie–how much I have seen and heard.”

The moment the authorities stole the tapes from Khosravi is when the paths of all involved dramatically shifted. Khosravi knew that when the police watched his footage, his life and the lives of his subjects would be in immediate danger.

Naz explains, in one of many examples of abuse in the film, that “members of Corruption Prevention of the Islamic Republic raped me in the month of Ramadan four or five years ago. They kicked me, beat me, used an electric baton. It started when I was being harassed by a man on a motorcycle. They told me they were going to help me,” she drifts off despondently. “Just this new year, again, I was kidnapped and raped. It’s not just once, it’s not just twice. The armed forces are the worst organization for mistreatments I have received.”

Naz is indeed caught in an untenable situation. As Yousefi explains, it is not technically illegal in Iran to be transgendered but “hangings and people getting killed pertains to a word that I hate: ‘buggery.'” Yousefi spits the word from his lips.

“If you are caught in that act, you get hanged,” he continues. “Being transgendered, you consider yourself a woman but cannot possibly afford surgery. In Iran, gay equals buggery equals death. The difference is that because you are trans, the authorities see it as their right to take advantage of you.”

In the film, Naz and her trans friend Maryam tell of dozens of rapes between them. Naz once attempted suicide but when the authorities responded, “even in that condition, they wanted to rape me,” she recounts.

The stories themselves are horrifying, but perhaps even more so is the surreal juxtaposition of heartbreak and deadness in Naz’ eyes each time she tells another piece of her history. Her words illustrate the emotional duality of a woman who knows she deserves the basic human rights she is denied but who feels no self-worth at all.

“I was born in this country,” she tells the camera. “I don’t have the right to breathe. I don’t have the right to study. I don’t have the right to blend into society. I don’t have the right to anything. When the authorities see me, they see a leper… So many times I have been raped. It kills your soul. You feel yourself getting destroyed each time.”

These testimonials will likely haunt all who see this film. Khosravi admits to being deeply affected. “That is what caused me to give everything up and follow this,” he says, having literally done just that.

When his footage was confiscated by the government, he had to flee Iran immediately. “Had I been captured in Iran, all the work we did would have been wasted,” he says. “At least we have the footage to point out and establish that these people are there. It makes it harder for the [Iranian] government to pick on them because of the international attention on them.”

Determined to complete the film, he chose to seek asylum in Canada because of this country’s reputation for trans acceptance and human rights protection. Landing with about $29 in his pocket, relatives here gave him shelter and the chance to complete his work. That energized him, but he was disenchanted by the lack of urgent action from Canadian human rights and government groups. “I came to Canada thinking there would be resources, there would be help, there would be interest,” he says. “But that is not what I experienced.”

Vancouver lawyer and activist barbara findlay, who herself appears in the film, echoes Khosravi’s concern. “I want people to understand that we’ve got a long way to go,” she says. “I want people to wonder about the situation of trans people in Canada, which is not nearly as far from the Iranian situation as we’d like to think.”

The risks taken by those who produced and appear in I Know That I Am will only be compounded when the film debuts this month at the Vancouver Queer Film Festival. “It was quiet for a while because the [Iranian] government assumed that they had all the footage,” explains Yousefi. “They didn’t know some was left. Now that the movie is going to be released, they will be looking for people. There will be people captured. That is why we are trying to get as many of them out of the country as we can.”

After Khosravi fled Iran, he scrambled to locate Naz, Maryam and all the other non-anonymous film subjects. At first, a horrifying rumour emerged that Maryam had been murdered.

“Thank God we know now that she’s alive but it is not all good news,” Yousefi explains. “She is in jail. We don’t know why and we don’t know where.”

Naz has been located in Turkey, and Yousefi and Khosravi both send what little money they can back to Iran in an effort to bring the women to safety. They are many thousands of dollars short of their goal.

The pair are committed to finding help for the women, to telling their stories and to bringing new awareness to the unacceptable human rights violations going on against trans people, not just in Iran but everywhere.

“We’re not going to lose hope,” says Khosravi passionately. “I’d rather die than be hopeless. We’re going to fight to the last minute; whether it is getting family and friends involved, whether it is talking to you, everything that we are doing is to get them as much help as we can.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra