Credit: Xtra West files

A camera pans over clasped hands; some fingers toy nervously with a ring, others intertwine, a thumb kneads the handle of a coffee mug.

Faceless voices intone about first, surreptitious same-sex encounters. A woman’s voice imparts the wonder, after all this time, of an “amazing” first kiss with another woman.

A trans man remembers the female incarnation of himself at age 11, having a relationship with a girl —”fumbling, and probably silly.”

And there’s the incomplete memory of an encounter, maybe a relationship, gone wrong in an interior town that caused “a bit of scandal” resulting in packed bags and a quick exit.

The Love That Won’t Shut Up is 22 minutes long. Verbal and non-verbal snapshots of seven people remembering what it meant to be queer in Vancouver in the ’60s and ’70s.

A collaboration between musician and lyricist Veda Hille and storyteller Ivan Coyote, the short, personal interview-laden documentary tracks a history that, according to one interviewee, is lost.

“Nobody writes it,” asserts Bill Monroe, a self-described male actress, drag queen, and female impersonator. “They only write sad stories. You have to die in the end. That’s the only way a gay book could be because God punished you for being that way.”

It doesn’t help, he notes, that the whole community is geared towards the 15 to 30 age demographic.

“After that they used to think we were finished. Bang! Kaput! I wanted to show in the history [that] people in their mature years still [are] a viable, positive part of the community.”

For Monroe, participation in the film provided a multi-faceted opportunity: speaking to the nuances of identity during that time, the changes he has observed over time, and addressing misperceptions about gay men.

“I can speak maybe for gay men only because I’ve never been a gay woman, so it’s very difficult,” he quips.

He remembers a time when it was just plain common sense and a self-preservation tactic to speak guardedly in public about relationships or hook-ups with friends.

“It was a code, so that you could talk about your friend sitting beside another friend, say on the street car or the bus. I couldn’t very well say George picked up the cutest guy last night. I’d be bonked on the head. But if I could say George’s, shall we say, code name was Gigi, and Gigi picked up the cutest guy, nobody would pay attention.”

Then there was the threat of blackmail, Monroe adds.

“You could lose your job, so nobody ever was really, in the ’50s, out. You’d have to be independently wealthy, or have a career as a dancer or a hairdresser, or something like that, to be out. “And even then,” he points, “it was still dangerous.

Still, says Jesse MacGregor in the film, “you could only hide for so long.”

MacGregor recalls breaking the news to his parents that all was not what it seemed when it came to his sexuality and gender identity.

“I sat my parents down and I said, ‘You know how you think I’m your daughter. Well, actually, I’m your son.'”

One of the more moving moments of the film comes when an emotional but “very lucky” MacGregor talks about the great effort his mother makes to get his pronoun and identity shift right.

“This 82-year-old woman, who is very gracious, and who really works hard at getting the “he’s” correctly, and making sure she describes me to others as her son. I don’t know how that’s possible for her.”

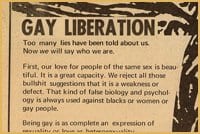

For some of the interviewees, the reflex, at least some of the time, was to keep things on the down low. Gordon Hardy, founding member of Vancouver’s Gay Liberation Front (GLF), says he “learned protective camouflage.” Friend and co-GLFer Arthur Giovinazzo says it was “instinctive” not to tell.

Lawyer Diana Davidson says she didn’t want to go to jail for fear of losing her kids. Conversely, she was adamant about not being quiet, much to the distress of her mother, who once asked Davidson if there was a possibility she could keep her mouth shut.

“Absolutely not, Mom,” Davidson remembers answering. “It’s all I’ve got.

“The only thing I had besides all those kids and a lot of pride was that I never lied,” she emphasizes.

What struck Coyote in listening to and observing the seven interviewees was “how incredibly brave” they were —”and still are.”

“Sometimes we walk right past them and don’t recognize each other,” says the incredulous storyteller.

“As gay people, that history is hidden from us because we hide ourselves within our families. [So] every generation recreates itself without having any sense of their history, or where they came from,” Coyote observes, adding that one of the film’s main goals is to preserve the story and history so that “people can take from it what they want.

“I hope there’s young people who are interested enough in their own history —and I mean queer history, I don’t mean their racial history, or their socio-economic history or their national history —that they’ll go track down the whole interview on the people. I just want to keep the stories available to those who are interested.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra