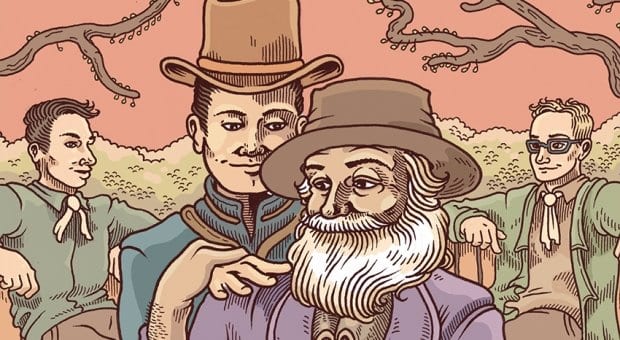

One of my favourite pieces of writing by 19th-century American poet Walt Whitman isn’t oft-quoted “O Captain! My Captain!” or the erotically charged “I Sing the Body Electric,” but an excerpt from his diaries that is essentially a 46-year-old Whitman perving on a cute boy.

Whitman’s parents were descendants of early Long Island settlers; his father moved the family to Brooklyn when his son was four. At 11, Whitman left formal education and alternated between teaching, printing and writing jobs. Much of his early writing was included in his breakthrough Leaves of Grass, published when he was almost 36. During the Civil War he toiled as a “sustainer of spirit and body” in Union military hospitals, providing physical comforts — treats, tobacco, booze and company — to thousands of injured soldiers. A perpetual note-taker, he documented the constant flow of young men. On Feb 28, 1865, near the bloody war’s conclusion, he met John Wormley, “a West Tennessee rais’d boy, parents both dead — had the look of one for a long time on short allowance — said very little — clear dark brown eyes, very fine — didn’t know what to make of me — told me at last he wanted much to get some clean underclothes, and a pair of decent pants . . . Wanted a chance to wash himself well, and put on the underclothes. I had the very great pleasure of helping him to accomplish all those wholesome designs.”

Whitman wrote extensively about the physical and spiritual beauty of both men and women. In “Once I Pass’d Through a Populous City,” he documents what was likely a love affair he had on an 1848 visit to New Orleans. To this day the widely published version describes a woman, although in 1925, the original, handwritten manuscript was uncovered, revealing Whitman had reversed the sex of his left-behind lover. This occurs in a great deal of Whitman’s work: the original manuscripts exchange pronouns, or “him” is crossed out and replaced with “her.”

Whitman’s diaries reveal he kept a great deal of same-sex company, chief amongst them a bus driver named Peter Doyle, who became a lifelong companion. Doyle later described their meeting: “We were familiar at once — I put my hand on his knee — we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip — in fact went all the way back with me.” Whitman also kept lists of his boys: “George Fitch — Yankee boy — Driver . . . Good looking, tall, curly haired, black-eyed fellow,” and “Dan’l Spencer . . . somewhat feminine . . . slept with me Sept 3d.”

In life and his work, Whitman was a flirt; he loved everyone without prejudice. Everything in the world served the purpose of beauty, even the ugliest bits of war and disease. His writing, often decried as “immoral” or “pornographic,” became a lightning rod for gay contemporaries. Edward Carpenter, an early English gay activist, corresponded with Whitman, championing the cryptic though recognizably gay elements in his writing. Late in life Whitman spoke of this friendship to his biographer Horace Traubel: “Edward was beautiful then — is so now: one of the torch-bearers, as they say: an exemplar of a loftier England: he is not generally known, not wholly a welcome presence, in conventional England: the age is still, while ripe for some things, not ripe for him, for his sort, for us, for the human protest: not ripe though ripening. O Horace, there’s a hell of a lot to be done yet: don’t you see? A hell of a lot: you fellows coming along now will have your hands full: we’re passing a big job on to you.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra