Sheila Cavanagh's academic work forms the backbone of Queer Bathroom Monologues.

Living with Henry is a musical about HIV.

"The Fringe is one of the only places where you'll be able to see things like this," says Tony Dunn.

With Pride season upon us (remember when it was just a day?), there are plenty of options for Toronto queers looking for some hot entertainment in our sizzling city. But after the crowds disperse and the bowel-shaking bass is mercifully silenced, be sure to head over to the 22nd annual Fringe Festival, running July 6 to 17 right here in Toronto.

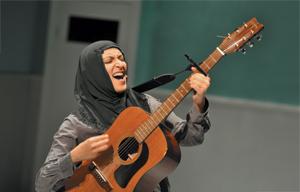

Muslim. Female. Lesbian. No, it’s not a game of One of These Things Is Not Like the Other. It’s the theme of Zehra Fazal’s play Headscarf and the Angry Bitch. Z Headscarf, a Hedwig-esque entertainer, has landed a gig as cultural ambassador to her local community centre. The hope is that her songs and stories will help educate others about Islam, but Headscarf gets a little carried away and ends up revealing far more about herself than many of her fellow Muslims expect.

“Yes, it’s pretty autobiographical,” laughs Fazal, who has taken her one-woman show across the US in a bid to discuss gender, sexuality and religion in Islam. “Z confesses that she lost her virginity during Ramadan and that she doesn’t pray five times a day, but she’s trying to adhere to the rules and hold on to what she can.”

Fazal confesses that her own journey as a bisexual Muslim has been a little rocky at times, but she is encouraged by the moderate forces working within her faith to find change and balance.

“I think that for a lot of us, we’re kind of realizing we’re not alone in this anymore,” she says. “While there’s certainly a lot of difficulty in families and home environments, there are things like the recent retreat for LGBT Muslims in Philadelphia. Things definitely are changing. There is a grouping going on, with a community and support system being formed.”

“I think that, post 9/11, a lot of Muslims felt the need to defend the religion they were raised in, while still exploring their own relationship with it. It’s good to put moderate voices out there… that’s what’s sorely missing in the debate within the media now.”

***

Peeing in public

Did you know that in Canada, it isn’t legal to enforce gendered bathrooms? That’s right, ladies: the next time you’re standing in line for a toilet, there’s no law stopping you from popping a squat in the nearest men’s room. That’s just one of the powder-room revelations in Sheila Cavanagh’s Queer Bathroom Monologues, a verbatim theatre piece premiering at this year’s Fringe.

The monologues are based on Cavanagh’s recent book, Queering Bathrooms: Gender, Sexuality and the Hygienic Imagination. “I did 100 interviews with LGBT folks in major Canadian and American cities,” says Cavanagh. “It’s about homophobia and transphobia in the public bathroom.”

Revealed are true stories of what goes on behind restroom doors, be it sex, assault, conversations or transgressions against some of our most vulnerable brethren.

“The common things I was hearing was that those who were trans or gender variant are frequently denied access to public bathrooms or questioned by other occupants,” Cavanagh says. “Sometimes the police have even been called, as the victims have been viewed as would-be predators.

“We all need to be able to access public facilities; otherwise, our freedom to move in public is severely curtailed. Some even developed bladder and kidney problems because they delay urination.”

In adapting the book for the stage, Cavanagh has cast three actors to portray bathrooms according to their genders. Hallie Burt will represent a female restroom, Chy Ryan Spain a male facility, and Tyson James is cast as a trans commode. The three will share stories of scenes they’ve witnessed within their tiled confines and posit possible solutions to bathroom bigotry.

There will also be other interesting tidbits, including the origin of gendered bathrooms and the first ladies’ room in the Big Smoke.

“The first women’s bathroom in Toronto was built in the late 1800s by Timothy Eaton,” says Cavanagh. “This was the first place where women could legitimately pee in public. The bladder can act as a leash to the home, and Eaton wanted women to venture out for longer periods of time.”

***

At loose ends

Pascal is a young revolutionary in 19th-century France. Looking for escape from the violence unfolding in Paris, the young man (played by Michael Davidson) flees to the peaceful town of Bordeaux’s picturesque vineyards and sedate lifestyle. There he meets two sisters, Odette (Alexis Eastman) and Genevieve (Julia Pileggi), daughters of an old grape farmer who expects his girls to carry on the family business once he’s gone.

Odette feels the pull of her father’s wishes and prepares to plod on in his footsteps, even as she falls in love with Pascal. Genevieve is also drawn to the young stranger’s charisma and charm and is inspired by tales of his Parisian exploits. All is bucolic splendour until the arrival of Henri (Jamie Ebbs), a crossdressing opera singer who has travelled from Paris, ostensibly with news from the revolution but in truth as a bid to rekindle his and Pascal’s previous (and secret) romance.

“They’re really four disparate characters living on the fringe of society,” says playwright Alex Kentris. “But they’re all living a lie in some ways. Odette doesn’t want to inherit her father’s vineyard, Pascal doesn’t want anyone to know about his relationship with Henri, and Genevieve just wants to do anything to get out of the small town.”

Kentris set Bordeaux in 19th-century France but feels the social and political struggles of that time and place are still very relevant in today’s culture.

“I’m interested in the way we can use the historical to comment on now,” he says. “These characters are going through problems that feel very contemporary for me. It was the beginning of the modern era, with that sense of social anxiety where things are moving so fast that we can barely keep up with them. It’s the same now.”

The four friends find themselves bound together by a shared sense of being outcast, but as their relationships deepen and truths emerge, fractures begin to form.

“It isn’t necessarily about society not accepting people, but more the way the characters have internalized things like homophobia. Pascal and Henri reject and hurt each other even though they’re part of the same community. I think that happens a lot in our own gay community. Two gay men rejecting each other hurts way more than a homophobe hurting you.”

***

Remember to breathe

For those of us who are closer to retirement than puberty, HIV and AIDS still hold some pretty traumatic memories and associations. What used to be a sentence of prolonged suffering and certain death has now become a disease that can be managed through advanced treatment and drug therapies. Actor/singer Christopher Wilson sets forth to sort out these new realities in Living with Henry, a musical drama premiering at this year’s festival.

Michael (played by Ryan Kelly) is puzzling through his changing life as HIV/AIDS wreaks havoc on his relationship with his best friend (Lizzie Kurtz), his mom (Mary Kelly) and his husband (Christian Bellsmith). A near-death experience brings each conflict to a head.

Wilson based the story on his own experiences living with the disease for the past 10 years and wrote it after the breakup of his marriage.

“It was an incredible journey that I took over the last three years,” he says. “In my life, what took precedence was fear. There I was in my mid-30s, realizing that my mortality was contingent on medication. Fortunately, these medications do exist that allow us to live day to day, like we’re living with diabetes or something.”

Despite HIV’s metamorphosis from death sentence into manageable disease, Wilson still finds he needs to educate people on the nature of his diagnosis.

“One of my favourite discussions with many people is that I had AIDS, and they say I still have AIDS. But AIDS only exists when the immune system is in jeopardy. The fact is that AIDS is often reversible. Four years ago I was dying of AIDS and had about seven blood cells left in my whole body. Now I pop one pill a day and carry on as normal.”

***

A prisoner of misogyny

Tony Dunn has never been to prison. But the possibility that he could have done time still looms in his mind. The Wisconsin-born Toronto-based theatre director came to Canada in 1970, dodging the Vietnam War draft, an act that could have put him away for years.

“I would never have survived prison, so I had to escape the country,” he says. “Once a year an FBI agent would visit my parents, asking if they knew where I was. I couldn’t go home without the possibility of landing in jail.”

“I thought I would be able to get out of it because I had a letter from a psychiatrist that said I was gay,” he adds. “But they didn’t believe me, so I had to run.”

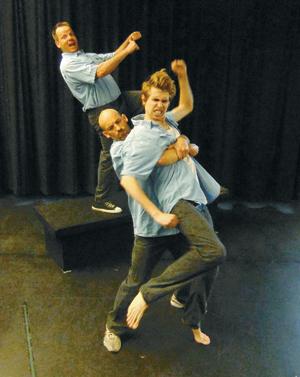

Perhaps Dunn’s fear of landing behind bars inspired him to tackle lesbian dramatist Megan Terry’s 1965 play Keep Tightly Closed in a Cool Dry Place. The rarely performed work by the pioneering feminist playwright details the lives of three men in prison. Exploring bullying and male bonding, as well as homosocial behaviour and the roots of violence, the work doesn’t immediately announce itself as a piece of feminist writing.

“Terry was exploring how men will often do everything in their power to kill the feminine elements inside them,” he says. “But we can’t.

When we try to repress those things they still come out, but in more violent and unpredictable ways.”

The production marks a return to the director’s chair for Dunn, after a nearly 30-year absence. Although he holds degrees in theatre from the University of Victoria and York, Dunn worked most of his adult life running a home furnishings store on the Danforth with his husband.

Now in retirement, he’s excited to return to the art form and credits the Fringe Festival with making such things possible.

“Producing theatre can be very expensive, and the festival allows artists to try things out they couldn’t possibly afford to produce elsewhere,” he says. “This is not a commercial play, and the Fringe is one of the only places where you’ll be able to see things like this.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra