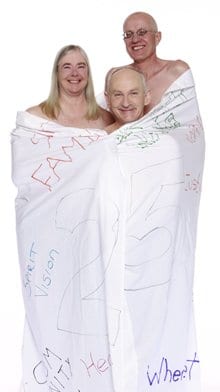

“She was a bitch,” says Little Sister’s co-owner Jim Deva. He’s sitting in a raised office area in the Davie St store, behind the front counter. He’s explaining how he and his partner Bruce Smyth chose the name for Canada’s most talked-about independent bookstore, which turned 25 on Apr 15.

Before Little Sister’s, Deva worked for five years in a game store in Gastown. Little Sister was the daughter of the store’s cat.

“She was born on the top of a shelf in the warehouse,” Deva recalls. “One night she had struggled out and fell. Her head had been caught between two planks and she hung there all night until we found her in the morning. We thought she was dead but somehow she’d survived. That was it; I had to have her. But she had a real shitty attitude about life.”

The new bookstore’s mascot turned out to be anything but hospitable when Deva and Smyth officially launched Little Sister’s first location on May 3, 1983, on the second floor of a former residence in Vancouver’s West End.

“She would sit on top of the shelves and jump on people. If you touched her you had a 50 percent chance of lacerations. She’d even jump on dogs and ride them around the store. We had to keep bandages and put up a ‘Please don’t touch the cat’ sign. After five years she’d had it and on the day of our fifth anniversary, she left. She never came back.”

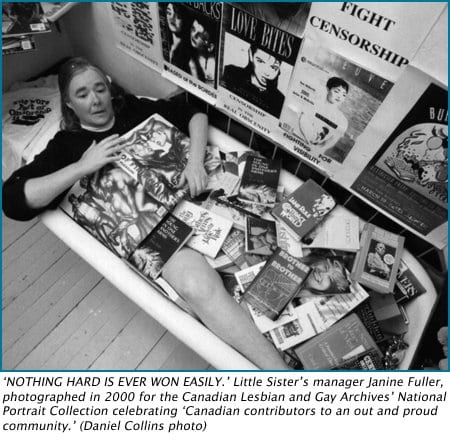

It’s early on a Sunday morning during the long Easter weekend. Below us, store manager Janine Fuller tends the till.

Upbeat music plays softly on the sound system. It tendrils through the store’s cheerfully lit and spacious layout, touching shelves generously stocked with books and magazines, caressing colourful displays of Pride items such as rainbow key rings and declarative t-shirts, and flirting with racks and wall units containing the latest in sex toys and aids.

Other than that it’s unusually quiet; just a couple of customers. While kids across the city hunt for candy eggs and chocolate bunnies, Vancouver’s gay community, which constitutes most of the store’s clientele, isn’t quite ready to rise.

The theme of resurrection is pertinent to Little Sister’s. The store is for sale. Many other North American gay and lesbian bookstores have died off in recent years: Crossroads Market in Dallas; Lambda Rising in Baltimore; Beyond the Closet in Seattle. Montreal’s L’Androgyne is gone. So is Victoria’s Bleeding Rose Books. New York’s The Oscar Wilde Bookshop, which became the world’s first gay bookstore when it opened its doors in 1967, was about to fold a few years ago when a benefactor stepped in at the last moment. But it’s been considerably downsized.

Has the gay movement passed its shelf life? Is gay identity caught in a time warp?

When the demise of The Oscar Wilde Bookshop seemed inevitable, American author David Leavitt wrote a piece for The New York Times claiming that this was symptomatic of our successful integration into the mainstream. You can buy gay titles in big box book chains so why do we need a specialty bookstore?

The jacket blurb for a paperback edition of The End of Gay (And the Death of Heterosexuality) by Canadian writer Bert Archer reads, “Gay is a phase. Not something people go through in adolescence, but, like feminism, a cultural, historical movement, on the way to something bigger.”

Like what? Wal-Mart?

“Try walking down a street in small town Ohio holding your boyfriend’s hand and tell me gay is over,” says Ken Boesem, who works part-time at Little Sister’s. Boesem is an illustrator and cartoonist. His comic strip The Village appears in Xtra West. He grew up in a small town in BC’s interior where being out wasn’t an option.

“Most people don’t just think of Little Sister’s as a bookstore. It’s known as a Mecca outside of Vancouver for gays,” says Boesem.

During a lunch break a few doors down at The Majestic Lounge, Robert Kaiser concurs. His drag persona Joan-E, a tireless performer and community activist, received recognition from no less than the Queen herself a couple of years ago for her charitable works.

“Little Sister’s is like the General Store,” Kaiser says. “It’s where you go to find out what’s going on and get the gossip. They know everything.”

***

As the day progresses, more and more people filter through Little Sister’s doorway, many of them pausing at the bulletin board, looking for roommates, rentals or whatever else may be posted, or sifting through stacks of free publications, before they snoop around to see what new books or sex toys have arrived.

Others are here for a friendly catch-up and to find out what’s going to happen to the store. Richard Boulier is one of them.

“I arrived in Vancouver when the Davie Village was just getting started,” says Boulier, who, like Boesem, is originally from a small town in BC’s interior. “Little Sister’s was already like a landmark. Just like today I’d just drop by and breeze through the postings and chat with whoever I might see, and maybe end up being introduced to new people. It’s much more of a community centre than anything else.”

Boulier liked Little Sister’s and its old location so much that when the space below became vacant, he rented it and turned it into Friends café. The café lasted a few years until 1998 when Boulier moved away. He returned to Vancouver last year.

“I think that for anyone who’s had any experience with Little Sister’s over the years and watched them grow, then left and came back, it’s like coming home. The one constant is the staff. There are some people who have been here a long time and they’re still behind the counter. Whether you buy something or not, they are here to interact and talk.”

Fuller remembers her first few days on the job in 1990.

“When I first worked at the bookstore there was a coffee machine that you had to put a quarter in and press a button. It was hysterical. They sold cigarettes and everyone smoked. Here I am coming from the Women’s Bookstore in Toronto that was a collective, into an atmosphere that was so fun, and also, just everything was there. The store has kept this incredible ability to just keep moving with the times.”

“We didn’t know anything about running a bookstore but it drove us crazy that you couldn’t find gay and lesbian books,” says Deva. “There was one bookstore on Davie that was owned by a lesbian where you had to go to the back of the store and get on your hands and knees to find them.”

In the store’s early days, Deva and Smyth literally lived at work, sleeping in a tiny room at the back. The store was their living room, their home.

“You have to keep your costs to a minimum,” Deva explains. “People make that mistake — they think they can keep their lifestyle. Any dollar you make in profit you have to put back into your business. I never took a holiday for two and a half years. We worked every day, seven days a week.”

Today Fuller describes Little Sister’s as a “major focal point” for community activism and connection, a place where people converge to respond to events, to gather and share information and to strategize.

“Many a march has started from here,” she says pointing, for example, to the 2,000-person protest that marched silently down Davie St in November 2001 after Aaron Webster was brutally beaten and left to die at the entrance to Stanley Park’s gay cruising trails.

“When Little Sister’s opened it marked a turning point,” says Kevin McKeown, who penned one of Canada’s first gay columns in the Georgia Straight beginning in 1968.

Prior to the bookstore’s opening, Vancouver’s gay community was “pretty much a bar culture,” McKeown remembers. Little Sister’s helped change that in the early 1980s. “It was a benchmark in the gay community. It was about being visible at the street level and pissing on the corner and saying this is who we are.”

***

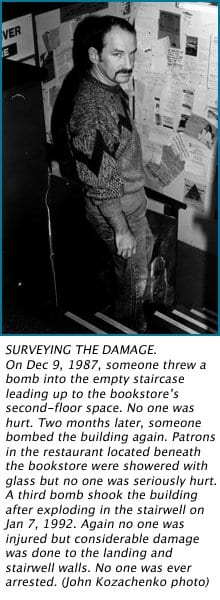

But pissing too loudly carried some risk. Even before Deva and Smyth opened Little Sister’s, they were warned that shipments crossing the Canada/US border could be detained if they contained material contravening vague obscenity laws — laws that would, by 1985, explicitly bar depictions of anal penetration from entering Canada. (See sidebar on this page.)

The onus would be on Deva and Smyth to prove that any detained books or magazines were not obscene within 90 days.

Deva remembers talking to importers of porn who encouraged him to stay under Canada Customs’ radar.

If anything gets seized or questioned, just let it go, they advised; challenging the authorities would only shine a bright spotlight on the store.

Back then visibility meant vulnerability, but Deva and Smyth weren’t “down low” types.

The same year Little Sister’s opened its doors, AIDS became a real concern for gay men in Vancouver, no longer a whispered horror far away in New York or San Francisco. We were terrified. We were dying. And no one would pay attention. Our voices needed to be heard, or else.

A place like Little Sister’s was the natural destination for anyone who was frightened, angry or confused, or all three. In those early years of the epidemic it was a safe place — just about the only place — to find reliable information, not to mention discussion and debate without judgment. Sometimes that reliable information got stuck at Customs and labelled obscene.

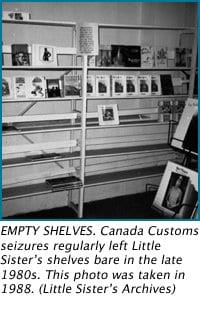

Within two years of opening, Little Sister’s imports had drawn Canada Customs’ unwanted attention. At first the seizures were small and occasional; tolerable if reprehensible. Then Customs agents seized the bookstore’s 1986 Christmas shipments and everything changed.

On Dec 8, 1986, Little Sister’s received notice that Customs had seized 59 titles and were withholding the bulk of the bookstore’s Christmas stock. “That’s when we figured out they had the power to put us out of business,” Deva says.

He and Smyth had a decision to make: fight the government and risk losing everything, or not fight and risk losing everything.

Business concerns aside, both were deeply troubled by what seemed like a complete disregard for the Charter of Rights’ guarantee of freedom of expression, not to mention Customs’ discriminatory targeting of gay materials.

When Customs agents detained another 19 titles two days later, the store put out a press release entitled, Canada Customs Declares War on Little Sister’s.

“The detention of these books during the Christmas season, when most bookstores do one third of their yearly sales, has to be viewed as a direct attempt to put the store out of business. With over $4,000 dollars worth of books seized and detained by Canada Customs during the month of December Canada Customs has become Little Sister’s main threat to its continued existence,” the press release read.

“The agent responsible for the present seizures has threatened to continue with the stringent examinations and long delays until the store is no longer a viable entity,” it added.

By the end of December, Customs had seized more than 600 books and magazines bound for Little Sister’s, including 75 copies of the Jan 3, 1987 issue of The Advocate.

Customs eventually released many of the seized books, stuffing them into a mailbag and dumping them unceremoniously on the store’s Thurlow St steps. “They just threw them on the step like it was trash,” Deva recalls.

And the seizures continued.

Smyth and Deva knew they’d need allies if they were going to stand up to Canada Customs. And cash.

Vancouver’s gay community rallied immediately. Sometimes there were two fundraisers a night to raise awareness as well as money. Little Sister’s was going to need every last penny raised.

With help from the BC Civil Liberties Association, Little Sister’s soon got a lawyer and began the lengthy and costly process of challenging Canada Customs’ discriminatory targeting of its shipments and its authority to seize ‘obscene’ materials and refuse them entry into Canada. Together, they filed a Charter challenge in June 1990.

Four years and numerous delays later, the bookstore finally got its 40 days in court.

***

In Little Sister’s vs Big Brother, Aerlyn Weissman’s film about the bookstore’s two-decades-long legal battle with Canada Customs, American author Sarah Schulman (After Delores, People in Trouble, My American History) poignantly recalled her main reason for testifying at the store’s BC Supreme Court trial in 1994.

“At the time, so many of my colleagues had died or were dying at that moment that we really experienced the disappearance of a literature. So to see these writers dying and their books being forgotten and at the same time have a government try to speed up the forgetting process, it was really just too much.”

It was too much for the American publishing community in general. On one hand, their publications were being detained, which was bad for business. On the other, this was unthinkable censorship for a western democracy.

In preparation for the 1994 trial, Fuller had attended American Bookseller Association trade shows and lobbied big name writers with clout to give their support. She felt like a stalker.

As news spread among American writers and publishers, outrage grew and Little Sister’s became something of a cause célèbre.

Here at home, not so much.

In the early years of Little Sister’s attempt to take its challenge to trial, the Canadian media and publishing community played deaf, dumb and blind.

“The Association of Canadian Publishers didn’t want to have anything to do with it. They would never want to listen to anything Little Sister’s was saying,” says Stuart Blackley during one of his evening shifts.

Blackley is a journalist and playwright, and works fulltime at the store. He co-authored Restricted Entry: Censorship On Trial, with Fuller. In the US, the book received the 1995 Editor’s Choice Lambda Literary Award.

“We tried to get some declaration made by the Canadian publishers. We couldn’t even get one line of support from them,” he says.

That changed after the media exposed a bizarre shipment fiasco highlighting Customs agent’s apparent fixation on Little Sister’s.

“By mistake, boxes of books that weren’t even coming to Little Sister’s got mixed up in the process and were put though the same drill,” says Blackley. “About 30 titles destined for mainstream bookstores were detained and notices were sent. There was even a Christian bookstore that got a notice saying its book was obscene. The Globe and Mail wrote about it.”

Most Canadian booksellers didn’t know that book shipments could be legally stopped at the Canadian border. Neither did most Canadian writers. It came as a shock and it quickly became evident that Little Sister’s was being targeted.

“I was among many people who were unaware of the power of Canada Customs,” says Nino Ricci, who was the president of PEN Canada at the time. He’s on the phone from Ohio where he is writer in residence at a Cleveland university.

According to its website, PEN Canada “works on behalf of writers, at home and abroad, who have been forced into silence for writing the truth as they see it. PEN Canada is for debate and against silence.”

Yet Canadian writers, journalists, publishers, booksellers and other members of PEN did not realize that a domestic law with the potential to regulate freedom of expression was right under their noses.

“We [Canadians] tend to be tolerant but dismissive,” says Ricci. He describes the events leading up to Little Sister’s 1994 trial as an exciting time. “It was scary and exhilarating to see Little Sister’s take on the case. It galvanized the writing community.”

Susan Swan, the current president of the Writers Union of Canada, says almost the same thing by phone from her home in Toronto. Swan is the award-winning author of What Casanova Told Me, Last of The Golden Girls, The Wives of Bath and other books.

“I think it is when we came of age and became stronger as a community of writers,” she says, referring to the time around Little Sister’s first court case. “It was galvanizing whether you were gay or straight, a watershed when you realized that you weren’t a minority of one. The censorship of books at the border is an international embarrassment and Little Sister’s is our flagship for freedom of expression.”

It was more than embarrassing; it was downright shameful.

The world raised an eyebrow in 1993 when PEN International called on the government of Canada — supposedly one of the most open societies on the planet — to “dismantle the system which permits such seizures to take place.”

The real kicker was the issue of prior restraint — seizing a book or magazine before it is vetted — and making the shipment’s intended recipient responsible for proving that the title in question wasn’t obscene. In Canada, you were guilty until proven innocent.

With the writing and publishing community and gay community joining forces, there was no way government bureaucrats could keep trying to sweep the issue under the carpet. As booksellers and publishers took action, it became apparent that homophobia was afoot at the 49th parallel.

On the eve of trial, in August 1994, Duthie’s bookstore in Vancouver ordered some of the same titles that had been stopped and banned en route to Little Sister’s; this time they went through Customs without a hitch.

In Toronto, David Kent did the same thing. Kent is an American transplant who moved to Canada because he thought it would be a good place to raise a family. He is the president and CEO of HarperCollins Canada. At the time, he was the president of Random House Canada.

“I made up a name and ordered some of the same titles that were stopped on their way to Little Sister’s,” Kent says by phone from his office in Toronto. “They came through with no problems. But I had to explain to my assistant why I had all these [gay and lesbian] books on my shelf.

“Little Sister’s is one of my favourite bookstores,” he says. “It takes a great deal of courage to stand up for freedom of expression and community. Little Sister’s does what all good bookstores do — represent its community’s interests, hopes, dreams and desires.”

From her BlackBerry at her Toronto hairstylist’s, where she is getting ready to travel out of the country for a sales conference, Louise Dennys, the executive publisher of Knopf Canada, takes time out to weigh in with her perspective.

“Little Sister’s has been one of the most important cases for anyone concerned about freedom of expression and the right to read what they want to read. Seizing book orders has been not just an attack on a small organization; it has been an attack on every reading Canadian. We can only rejoice at Little Sister’s spirit and courage for all Canadians.”

Marc Côté and Brian Lam are both openly gay publishers who make a point of publishing queer writers. Côté runs Cormorant Books in Toronto and Lam is at the helm of Vancouver’s Arsenal Pulp Press.

“Little Sister’s Bookstore — its owners, managers, and staff — are the standard bearers not only for the freedom of expression that so many publishers and film producers cherish, but also for the freedom to read that too many Canadians have taken for granted until now. Without Little Sister’s, the driving force behind important Charter challenges, and Little Sister’s, the bookstore, Vancouver and all of Canada would be poorer,” Côté writes in an email.

“Little Sister’s is really something to be treasured,” Lam writes, also by email. “It’s unique among bookstores not only in Canada but around the world; New York, London, Paris do not have a GLBT bookstore of the breadth, scope and commitment of a Little Sister’s.”

In an interview outside the courtroom in 1994, Pierre Berton, the late Canadian writer legendary for his straightforward opinions, said in reference to Little Sister’s ongoing court challenges, “I think the crux of the matter is whether or not minor civil servants have the right to tell me what I can read or what I should read or what I cannot read. I think in a democracy it can’t be allowed.”

Of all the people to testify at Little Sister’s trial in 1994, author Jane Rule was perhaps the most eloquent.

“Of course we have writers who are writing erotica, and so should we. I celebrate that. But we are not a community churning out sex tracts. We are a community speaking with our passion and our humanity in a world that is so homophobic that it sees us as nothing but sexual creatures instead of good Canadian citizens, fine artists, and brave people trying to make Canada a better place for everybody to speak freely and honestly about who they are.”

***

In January 1996, Justice Kenneth Smith of the BC Supreme Court ruled that Canada Customs had applied the law in a discriminatory manner against Little Sister’s. Clearly, the gay bookstore was being targeted. Clearly, the process was flawed. But the law itself was not.

Even as he backed Little Sister’s, Smith upheld the obscenity section of Canada’s Criminal Code and Customs’ authority to enforce it at the border.

Little Sister’s promptly appealed, still hoping to overthrow the law allowing Customs agents to screen and censor at the border. The case resumed its journey through the court system.

In December 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the Smith decision. It too found that Customs had been targeting Little Sister’s and told Customs to cut it out. But it also upheld the need to continue censoring obscenity — provided the law is applied equally to gay and straight materials alike.

The court did not find the existing definitions of obscenity to be a threat to freedom of expression, nor did it rescind Customs’ authority to seize materials at the border. As a result, Customs agents can still seize materials based on guidelines that define specific acts as obscene, even though most of them are readily available online and sometimes on TV.

Within a year of the Supreme Court of Canada ruling, Customs again seized several books bound for Little Sister’s, including two issues of Meatmen, a gay comic featuring SM scenes and other erotica.

Little Sister’s appealed again and the next chapter in its legal battle with Customs (now called the Canada Border Services Agency) ensued.

Knowing that it couldn’t hope to compete with the Crown’s extensive expert witness list without a significant infusion of cash, Little Sister’s applied to the court for advance costs, based on a 2003 Supreme Court of Canada ruling that granted an aboriginal group funding to take the government to trial.

The Supreme Court of Canada refused, saying Little Sister’s censorship case wasn’t “special enough to warrant an advance costs award.”

***

Despite all the challenges it has faced — and in part because of them — Little Sister’s still flourishes and is held in tremendously high regard within the community.

When the store sells, Fuller will stay on. Until then, Deva and Smyth say they’re not going anywhere.

“If we do find the right fit, then we’ll look over the fence. But not until then,” says Deva, reluctant to discuss any possible retirement plans prematurely.

He and Smyth say they have no fixed timeframe for selling the store, but they expect it will take at least another six months.

The right fit will be someone dedicated to working with the community and building community, they say, noting that they have heard from some interested parties.

But they won’t insist that the new owner or owners maintain every aspect of Little Sister’s exactly as is.

“They’re going to have to make some difficult decisions down the road, like we all have to do in small business, and they have to have the flexibility to move on the moment.”

Retail, and bookselling in particular, is a fast-changing environment, they explain. So is the gay community for that matter.

The new owners, whoever they may be, can’t be locked into specific plans; they have to be able to adapt and change with the times, Smyth and Deva say. “The last thing they should be worried about is pleasing us,” adds Deva.

News of the store’s for-sale status startled many community members, who are now keeping an anxious eye on Little Sister’s, wondering if the community centre they’ve come to love, trust and rely upon will still be there in a year.

Deva says he spends a lot of time these days reassuring customers and community members that “we’re not going to drop the ball and run.”

“This is probably one of the most critical decisions we have to make,” he acknowledges. “In the end, what we want to do is look back and see the store running well and say, ‘We did our best.’ So the ending is as important as the beginning.”

With files from Robin Perelle.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra