Even as popular culture makes space for gay and lesbian lives, the sports world remains cloistered in its own heterosexist silo, says former Canadian Olympian Mark Tewksbury.

“It’s incredible that sport has remained the last bastion of 18th-century thinking,” says Tewksbury, who brought home a gold medal for the 100 meters backstroke at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona while still closeted.

Everything else has progressed, he says, but the sports world stands out as the exception, as a large closet on an increasingly open horizon.

“It’s a very difficult place to be if you’re not straight,” Tewksbury said at Vancouver’s Q Hall of Fame launch last September.

“Sport is still top down from policy makers,” he explained to Xtra in 2006, after the release of his book, Inside Out. “It’s very dogmatic and rule-bound. People don’t want to change rule structures. It’s by nature highly conservative. It’s pretty much the last machinations of the old-boys club.”

No surprise then that Tewksbury waited until after he retired to come out.

“I wasn’t ready,” he says when asked why he didn’t come out during competition. “It’s a complicated issue. There was a lot of fear — fear of losing my coach, my teammates and my livelihood.”

If the average private gay citizen is afraid to come out, think how professional athletes feel, he said in 2006. “Think about that amplified exponentially because you’re in the public eye, part of this macho image world. You’re maybe physically putting yourself at risk. That’s what probably keeps a gay male professional team player in the closet.”

It’s fear of the unknown public response that keeps athletes in the closet today, Tewksbury says.

Jim Buzinski agrees.

Buzinski is co-founder of Outsports.com, a US-based online publication dedicated to gay athletes and sport. He, too, thinks athletes don’t come out because they’re afraid of how the public, their coaches and their teammates will respond.

“[Athletes] need some assurance that nothing will change and they will be treated the same,” he says, “and until they get that they will stay in the closet.”

The coaches, administration and straight athletes need to create an environment more conducive to coming out, Buzinski says. “There has to be more acceptance.”

“We need more people to come out in all areas of society and sport is no different,” he notes. “We are still waiting for people to come out and tell their stories so people don’t feel they are alone, [but] people don’t want to be the one out there by themselves. They don’t want to be the pioneer.”

Some surveys suggest that the highest-profile professional men’s sports leagues may be more welcoming than many gays and lesbians believe.

A 2006 Sports Illustrated survey asked pro basketball, football and hockey players whether they would “welcome an openly gay teammate?” Over half the athletes polled from the National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL) and National Hockey League (NHL) said yes.

The NHL was the least homophobic, with 80 percent of the 346 players polled saying they would have no problem with a gay member on their team.

The Sports Illustrated findings sound positive, Buzinski says, but the theory must be tested. “It’s nice to hear and it’s a positive step, but until someone active in the sport comes out and says, ‘I’m gay,’ no one will ever know how accurate the survey is.”

In another poll, conducted in 2005 by the market research firm Penn, Schoen & Berland Associates and released by Sports Illustrated, NBC and the USA Network, 78 percent of the 979 randomly surveyed Americans agreed that it is “okay for gay athletes to participate in sports, even if they are open about their sexuality.”

However, 68 percent of the respondents thought coming out would hurt an athlete’s career. And 62 percent agreed that “the reason there is so little coverage of gays in sports is because America is not ready to accept gay athletes.”

“There are seeds of change,” says former professional snowboarder Ryan Miller. “But there is still that dichotomy where people will come and say they don’t have a problem with [gay athletes] as long as they are not in [their] locker room.”

“I don’t know if it [professional sports] is the last closet,” muses Miller. “But it is one of the last.”

Miller speaks from personal experience. Ten years ago he was competing in Vancouver in one of his first professional snowboard competitions when he suddenly came out — a move prompted by taunts from teammates to go to a straight strip club.

The move transformed his career. He eventually had to seek another team and coach.

“I had had enough of it,” he says of his impromptu decision to come out at age 24. “I was so over the double life. I was trying to put on a second life for sponsors, teams and personal appearances. It was way too much energy and way too much stress.”

That night, dodging yet another round of testosterone-fuelled locker-room banter and uninterested in watching scantily clad women pole dance, he made an announcement.

“I’m gay and I’m going to dinner!” he told his teammates.

“There were only two or three teammates who would share a condo with me after that,” Miller says.

“Even though I wasn’t living a double life anymore it was almost as though I had to work harder in my profession,” he admits.

“There are still a vast majority of corporations that don’t want to engage [with gay athletes],” he adds.

Tewksbury doesn’t buy the sponsorship pressure argument. “That was the argument that kept me in the closet. ‘Oh you’ll lose everything, you can’t tell anyone.’ Let’s face it: there are so many gay characters in mainstream entertainment. There is an openness to it. It’s not like the public en masse has shunned this,” he told Xtra in 2006. “Why can’t that translate into support for a real person?”

“There’s probably an entire queer gamut of professional athletes,” says Betty Baxter, former head coach of the Canadian National Volleyball Team who was fired in 1982 for being a lesbian.

“But they can’t come out,” she maintains. “Queer people in sport are not going to talk. Not if the sport is important to them…. Not at the risk of losing your professional career.”

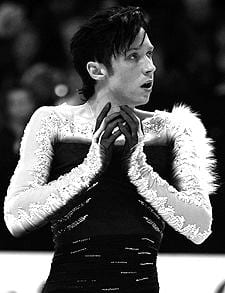

With a handful of championship titles under his belt, Johnny Weir won bronze at the US Figure Skating Championships in Spokane in January and set commentators’ tongues a-wagging with his exhibition skate to “Poker Face” by Lady Gaga.

The 25-year-old is generating a lot of buzz these days and is often described as flamboyant, colourful, eccentric and a diva.

In September, Outsports.com asked Weir about his sexual orientation.

“I think everyone has the right to ask people anything. But the way I see things like coming-out parties and being very theatrical and making such a big spectacle of things, I just don’t agree with making it a big spectacle,” Weir replied.

“I was born Johnny Weir, whatever that entails. People can make their own assumptions and people can talk and people can chat, but it doesn’t change who I am and all of these things that contribute to my life.

“Being gay? I’m all for it. I love gay people, I love African-American people, I love lesbians, I love Asians. To me, there’s no importance to making a show out of something that’s just you. I promote Johnny Weir and I’m as ridiculous as they come, but that’s what I want people to see is that I’m Johnny Weir.”

Despite numerous requests, Weir’s press team would not grant Xtra an interview.

“People talk,” Weir writes on his website. “Figure skating is thought of as a female sport, something that only girly men compete in. I don’t feel the need to express my sexual being because it’s not part of my sport and it’s private. I can sleep with whomever I choose and it doesn’t affect what I’m doing on the ice, so speculation is speculation.”

“If sexuality had no bearing [on sport] then people wouldn’t feel the need to talk about it,” Tewksbury counters.

Despite the apparent pressure on gay athletes to keep their sexuality quiet, the 2010 Games will see a groundbreaking flash of pink this month when the first-ever Pride House opens its doors to Olympians.

Conceived as an open and welcoming venue for all gay athletes and their allies, Pride Houses in Whistler and Vancouver will celebrate authenticity in sport — though organizers don’t know how many Olympians will venture inside.

“The primary rule of Pride House is really to create conversation. To create that dialogue and raise awareness of homophobia,” says organizer Dean Nelson. “If athletes choose to come and visit us and they’re ready to share their story as part of their personal journey, then we welcome them.

“But everybody is on their own journey,” he says, adding, “we’re creating a platform that people can utilize if they want to.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra