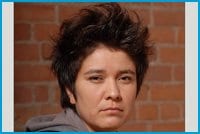

How lesbian poet and Mexican human rights activist Emma Beltran came to be in Canada is not a happy story.

Beltran says she was kidnapped at gunpoint by four men on a busy street in Mexico City on the night of Mar 23, 2001 and for seven days was subjected to a waking nightmare of physical and psychological torture at the hands of the Mexican National Army, and thus the Mexican government.

“I was blindfolded the whole time, but I knew that the place was in the countryside,” says Beltran, who came to Canada in 2002 and was granted refugee status in 2005. “It was quiet, and the air was fresh. Not like the city at all. I heard crickets when they moved me from the van to the building.”

At the time, Beltran, 32, was a writer-activist deeply involved in the national student and indigenous-rights movements in Mexico. She says that her kidnappers made it plain that her politics, including her open lesbianism, were the reasons for the torture.

Her new life in Toronto has her continuing her literary career and working for the rights of queer refugees to Canada, including writing a resource guide and practical advice book aimed at queer refugee status claimants.

“Gay and trans refugees face incredible barriers when they claim sexual orientation as the basis for their refugee status,” says Beltran. “They’re often just not believed. Or the immigration court insists that homophobia or transphobia in the home country can’t be that bad, because the country has some sort of official policy saying [gaybashing is] illegal. But the judge doesn’t know anything about the lives of gay people or trans people in that country, of course.”

Beltran speaks of a queer reality in Mexico that belies the reputation the country has among many gay tourists who visit the country’s apparently queer-friendly resorts.

“The resorts aren’t gay-friendly, they’re dollar-friendly,” Beltran says. “The people who run the resorts are all smiles for gay tourists with money to spend there. But they’d spit on the poor gay Mexican who lives near the resort, because he’s gay.”

Beltran knows of Mexican trans people punched in the face on subways for being trans. The antiqueer aspect of her own persecution was more extreme.

“During the seven days of my torture, I was repeatedly gang-raped. The men said that they knew I was a lesbian, that this would make me not a lesbian,” she says. “The blindfold only ever came off when they took photographs of me with a blinding flash, so I couldn’t see anything. But I know I would recognize those men today, by their voices.”

Beltran says that her own refugee status is based on her persecution as a political activist, rather than her persecution as a lesbian specifically.

She says that her persecution was triggered by work she had done as a journalist and broadcaster with the radical student radio station at the National Autonomous University Of Mexico in Mexico City, offering news and commentary on the national student strike that shaped the Mexican political scene in 1999 and 2000.

Beltran had earned a reputation for political radicalism as a writer and activist working in Chiapas, the southern Mexican state best known as the home base of the Zapatista Army Of National Liberation, the social justice movement for and by the marginalized of Mexico, particularly indigenous people.

From 1994 to 2000, she split her time between Mexico City and Chiapas coordinating political poetry-writing groups, journalism and theater workshops, and Spanish literature classes for indigenous activists.

“The indigenous people and the Zapatistan movement are queer-positive,” she says.

Today, Beltran is a member of the Writers In Exile Network Of PEN Canada, the organization for writers imprisoned and exiled by government regimes, and for freedom of expression. The Canadian PEN chapter is presently chair of the international network, and arranged for Beltran to work at the University Of Windsor in spring 2006 as exiled writer-in-residence.

Beltran’s English- and Spanish-language poetry has been published in the US, Canada, Mexico and Russia. While much of her work is on explicitly political themes, Beltran also writes flowing and lyric verse that suggests Romantic poetry of nature and love. Her poetry suggests that Beltran has a power to see beyond her immediate, pressing circumstances as one political refugee.

She hopes to eventually find a way to pursue her case back in Mexico through legal channels, and find justice.

“I’m not interested in justice for me, not at all,” she says. “I’m interested in justice for all of the victims of torture and political imprisonment in Mexico. If I could somehow use my case so that the UN condemns Mexico for its crimes, so that justice comes for the activists who have suffered there, that would be the ideal. That’s what I want.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra